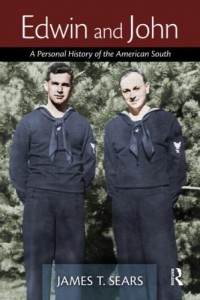

Edwin and John: A Personal History of the American South

Edwin and John: A Personal History of the American South

by James T. Sears

Routledge. 142 pages, $34.95

ONE REASON for the fragmentary nature of much of the gay historical record is the reticence on the part of members of earlier generations to discuss their lives directly. Even in the early decades of the 20th century, relatively few gay men had the opportunity to tell their story for posterity. This makes the publication of a book like James T. Sears’ Edwin and John: A Personal History of the American South a noteworthy event.

The product of years of interviews and back-and-forth editing with John A. Ziegler, now 97 years old, Edwin and John recounts Ziegler’s fifty-year relationship with his partner, Edwin Peacock. The book touches on everything from the 1930’s gay social scene in Washington, D.C., to the two men’s lengthy separation while participating in wartime efforts during World War II, their friendship with Carson McCullers, and their opening of a bookstore in Charleston, South Carolina, where they lived together for more than four decades.

The story of John’s years and his social circle in Washington, D.C., where he lived from 1933 to 1940, helps provide a welcome supplement and corrective to a previously lauded book, Jeb and Dash: A Diary of Gay Life, 1918-1945 (1993). John was a member of the group of friends surrounding “Jeb” (Carter Bealer), all of whom were given pseudonyms in Jeb and Dash—John’s being, inexplicably, “Little Nicky.” Editor Ina Russell also conflated events and changed details about her subjects, erroneously making John a marriage-destroying, suicide-attempting native Washingtonian. The reality was quieter. John’s recollections of living in a D.C. apartment house with several other gay men emphasize the domesticity of much of the scene: small and convivial parties, visiting back and forth between apartments, rowing on the Potomac River, attending the theatre.

Other than the obvious human interest in its recounting of everyday gay lives in years not often discussed, this section of Edwin and John is fascinating for the questions it raises about the nature of historical presentation. How is the historical record created? What methods are acceptable in putting forth material as “historical fact”? Is there any justification for Russell’s wholesale alteration of details in the earlier book? Have we passed the point in time where “changing names to protect the innocent” can be used for such justification? Some of these questions are particularly apt in light of James Sears’ own method of presenting the story in Edwin and John, which, while written by Sears, uses first person narration. In discussing this decision in his introduction, Sears admits that the method “may enrage the traditional historian” but seems willing to accept that reaction in exchange for creating an “as told to” memoir rather than a more academic one.

The appealing narrative, which reads as if John Ziegler were sitting at one’s elbow, telling his life story—albeit with frequent quotations from personal letters—may justify Sears’ method. The engaging voices that emerge in these letters to and from Edwin help carry the book’s lengthy middle section, where the lovers are kept apart by their respective duties during World War II. The sheer normalcy of their lives here and elsewhere in Edwin and John points to another theme of the book: the possibility for gay men to integrate completely into their surroundings, even in a time and place not normally associated with tolerance of homosexuality. Reunited after the war, the two men run their bookstore, they participate fully in the civic life of Charleston, and both have straight friends. Sears has John say the following:

As the years have passed, I have often thought back to social gatherings, warm friendships, and quiet acceptance from heterosexuals, wondering what all the fuss was about. … [A]mong about 25 gay couples whom Edwin and I knew intimately, all living in Southern cities, none had any problems with their identity as homosexuals. None actually “came out of the closet,” but, because of their lifestyles, staying with the same partner for 25 to fifty years, their same sex arrangements were obviously known. None of these friends ever had any problem about being accepted by relatives.

While John’s recollections may point toward acceptance only for gay men whose lifestyle was quiet and heterosexually imitative, they provide a counterweight to the gloomy portrait of pre-gay liberation life that many people have internalized.

This is not a memoir of the rich and famous but instead of two average men and their sustaining love. As such, it is all the more valuable. Edwin and John helps to fill gaps in our portrait of the pre-gay liberation era and the lives of some ordinary gay men who lived in it.

Philip Clark, a Washington D.C.-area writer, is the editor of new anthology, Persistent Voices: Poetry by Writers Lost to AIDS (Alyson Books).