VIEWED THROUGH THE PRISM of the eight issues of the newspaper Come Out! that were published by the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in New York from 1969 to 1972, the Stonewall Riots ignited a decisive and twofold political trajectory that has endured for forty years. Two political models, distinct and dissimilar but not mutually exclusive, developed simultaneously. The first approach sustained and refined the paradigm of identity politics rooted in the homophile movement. The second introduced a critical reformulation of gender and sexuality that evolved from feminism into the matrix of academia as lesbian and gay studies and subsequently queer theory.

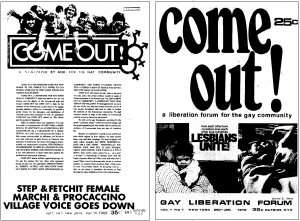

The premier issue of Come Out! was published in November 1969. The choice of title, with its  exclamation mark following a command, was meant to suggest a sense of urgency. Early liberationists understood that “coming out” had the capacity to be transformative because it turned a personal action into a political statement. The mission statement on the first page boldly proclaimed: “Come out for freedom! Power to the people! Gay power to gay people!” This rhetorical departure from the idiom of the early homophile movement, which had favored an understated, non-threatening tone, occurred at a unique historical moment. The lesbian and gay movement burst onto a stage of extraordinary cultural turbulence at the height the anti-Vietnam War movement, marked by a vigorous civil rights struggle, an emergent second wave of feminism, and a burgeoning youthful counterculture.

exclamation mark following a command, was meant to suggest a sense of urgency. Early liberationists understood that “coming out” had the capacity to be transformative because it turned a personal action into a political statement. The mission statement on the first page boldly proclaimed: “Come out for freedom! Power to the people! Gay power to gay people!” This rhetorical departure from the idiom of the early homophile movement, which had favored an understated, non-threatening tone, occurred at a unique historical moment. The lesbian and gay movement burst onto a stage of extraordinary cultural turbulence at the height the anti-Vietnam War movement, marked by a vigorous civil rights struggle, an emergent second wave of feminism, and a burgeoning youthful counterculture.

All the issues of Come Out! reported on gay and lesbian activist demonstrations in New York City. The protests were militant and the rhetoric was confrontational. Protests occurred in Times Square and Greenwich Village; at sites of institutional bigotry such as St. Patrick’s Cathedral; and against media homophobia at the offices of Time and The Village Voice. The first gay pride march was held a year after the Stonewall Riots, an annual tradition that survives and thrives to this day.

Also in Come Out! No. 1, Dr. Leo Louis Martello explained in “A Positive Image” that developing a positive self-image was a prerequisite for standing up to social oppression: “Homosexuality is not a problem in itself. The problem is society’s attitude towards it. Since the majority condemns homosexuality, the homosexual minority has passively accepted this contemptuous view of itself. Might is substituted for ‘right.’ The greatest battle of the homosexual in an oppressive society is with himself, more precisely the image of himself as forced on him by non-homosexuals.” Martello recognized the organizing power of identity politics, which must begin with people’s subjective experience and, through an analysis of oppression, develop a sense of membership in a minority group linked by their common relationship to the surrounding society.

The Come Out! mission statement departed from identity politics and crossed into a kind of proto-queer theory with a concise set of statements: “Because our oppression is based on sex and the sex roles which oppress us from infancy, we must explore these roles and their meanings. … What is sex, and what does it mean?” These observations and questions set the tone for a struggle that followed for decades, in which assumptions about the essential nature of gender and sexuality were thrown into question. (In 1968, Kate Millet had asserted in her pioneering book Sexual Politics that gender was an entirely social construction.) The question of sex roles echoed on the inside cover of No. 4, in 1970, with a gay liberationist quasi-manifesto. “Gay Liberation Front is a revolutionary homosexual group of women and men formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature. We are stepping outside of these roles and simplistic myths. We are going to be who we are.” The theme of rejecting or at least questioning conventional sex roles is one that came up repeatedly in Come Out!

In “Stepin Fetchit Woman,” published in No. 1, Martha Shelley posited a collective lesbian identity and acknowledged the intractable antagonism between gay men and women, proposing that “lesbianism is one road to freedom—freedom from oppression by men.” She contended that men fear the lesbian woman because of her total independence from men, her ability to obtain “love, sex and self-esteem from other women … a terrible threat to male supremacy. She doesn’t need them, and therefore they have very little power over her.” Arguing that women who are lesbians constitute a special case of feminist identity, she remarked famously, “I have met many, many feminists who were not lesbians—but I have never met a lesbian who was not a feminist.” She also suggested that lesbianism is inherently antagonistic to the patriarchal establishment, including the psychiatric establishment: “Hostility towards your oppressor is healthy—but the guardians of modern morality, the psychiatrists, have interpreted this hostility as an illness, and they say this illness causes and is lesbianism.” In 1980, more than a decade later, Adrienne Rich wrote in an essay, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” that “the work that lies ahead, of unearthing and describing what I call here lesbian existence, is potentially liberating for all women.”

Shelley’s pioneering inquiry into the subjugation of women helped to forge a liberated female identity, and her work anticipated the 1970 pioneering manifesto, “Woman Identified Woman,” by “Radicalesbians,” which appeared in Come Out! No. 4. This essay was initially distributed by a group called the Lavender Menace at the Second Congress to Unite Women, and it forced a discussion of lesbianism in the women’s movement. The name “Lavender Menace” was chosen after Betty Friedan, then president of the National Organization for Women (NOW), used this phrase to describe the lesbian element within the feminist movement. “Woman-Identified Woman” opened with a question-and-answer format: “What is a lesbian?” And the surprising reply: “A lesbian is the rage of all women condensed to the point of explosion. She is the woman who, often beginning at an extremely early age, acts in accordance with her inner compulsion to be a more complete and freer human being than her society—perhaps then, but certainly later—cares to allow her.”

Queer theorists generally acknowledge their debt to Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality (1978), which argued that sex roles are determined by social power rather than biology. In “Woman-Identified Woman,” the authors viewed lesbianism and male homosexuality as “a category of behavior possible only in a sexist society characterized by rigid sex roles and dominated by male supremacy,” implying that sexual orientation is mutable. The authors went on to contend that “Homosexuality is a by-product of a particular way of setting up roles (or approved patterns of behavior) on the basis of sex; as such it is an inauthentic (not consonant with ‘reality’) category. In a society in which men do not oppress women, and sexual expression is allowed to follow feelings, the categories of homosexuality and heterosexuality would disappear.” Sex roles of any kind are dehumanizing and relegate women to a subordinate “caste.” But sex roles also cripple men emotionally, “demanding that they be alienated from their own bodies and emotions in order to perform their economic/political/military functions effectively.”

Integrating lesbians and gay men into one movement after years of separation—principally under the aegis of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society—would remain one of the most contentious issues for the new coalition of activists. A recurring question for GLF was, “Can gay men and lesbians be allies?” This concern manifested itself in most issues of Come Out! By 1971, in No. 7b, the format of Come Out! changed to accommodate the nonnegotiable concerns of lesbians and gay men by sporting two separate covers, one side for gay men and the other side billing itself as “a liberation forum by and for the lesbian community.”

The appeal to gay men to examine their sexism reverberated through GLF’s brief history and animated Come Out! For example, in Tony Diaman’s 1970 article, “The Total Man,” No. 7a, he wrote: “Whatever we do, we have to go beyond our narrow roles to include both the masculine and feminine components of our personalities. To be a man, in straight society, is to be only half a human being, to be hard, tough, violent, aggressive, competitive, controlling. We must explore the other part of ourselves, be soft, tender, peaceful, unaggressive, cooperating, yielding.” Also in No. 7, the members of the 95th Street Collective wrote in “Five Notes on Collective Living”: “As long as we let the femme in us come through, our collective will continue functioning as a whole, not as one ‘man’ competing against another. I feel our collective has much to offer as an example to men who are still handicapped by a masculine image that is slowly dying, and which women and femme men felt as oppressive to us.”

In No. 4 (1970), in an essay called “Eat Your Heart Out,” Rita Mae Brown advanced the argument that gay people had internalized the stereotypical roles assigned to them by mainstream society. Thus, for example, she viewed gay male “camp” behavior as “part of the protective coloration for the homosexual intellect,” though she also defended camp as a creative adaptation that wasn’t a mere parody of feminine norms. Wrote Brown: “Most homosexuals live in a world of stylized, unreal communication. We artificially posture our way through alien territory. We are pseudo-heterosexuals. … We live in something very similar to those Busby Berkeley musicals. Our lives are highly stylized. We perform all the meaningless (to us) conventions of sacrosanct heterosexuality and we know the dreary dialogue by heart.” Brown saw gender as a cultural interpretation of biological difference, and gender as performative. This view anticipated Judith Butler’s work in Gender Trouble, where she associated gender with repetition and ritual, defined as performativity: “gender is manufactured through a sustained set of acts.”

Kenneth Pitchford’s poem in No. 7a, “The Flaming Faggots,” appropriated the epithet “faggot,” riffing off the OED definition that discusses the practice of using “faggots” to burn heretics alive. (When women were burned as witches in the Middle Ages, men accused of homosexuality were bound together in bundles “to kindle a flame foul enough for a witch to burn in.”) This attempt to own the word “faggot”—which included a fringe group called the Flaming Faggots and a publication titled Faggotry— didn’t convince too many people in the gay movement, though it did anticipate the subsequent attempt to reclaim the epithet “queer.”

The final issue of Come Out!, Volume 2, No. 8, came out in 1972 and introduced the ill-fated movement known as Effeminism, whose purpose it was “to urge all such men as ourselves (whether celibate, homosexual, or heterosexual) to become traitors to the class of men by uniting in a movement of Revolutionary Effeminism so that collectively we can struggle to change ourselves: from non-masculinists into anti-masculinists and begin attacking those aspects of the patriarchal system that most directly oppress us.” The Effeminists published articles in Come Out! and later in a magazine called Double-F: A Magazine of Effeminism, co-published by John Knoebel, Kenneth Pitchford, and myself.

Although Come Out! rapidly flowered with intense, palpable energy, it was to be short-lived. Perhaps there was no other course for it. The experience of working on Come Out!, as I did, often felt like an implosion about to happen. Aside from the tension between gay male and lesbian interests, there were platforms from other competing factions, such as Third World Gay Revolutionaries, and forceful transgenderist arguments from Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR). The newspaper’s influence would endure, however, and a compelling case can be made that it shaped the debate on sexuality and gender for decades to come.

The author acknowledges Perry Brass and John Knoebel for their diligent and meticulous preservation of the historically significant set of the Come Out! newspaper.

Steven F. Dansky, an original member of GLF in 1969, worked on Come Out! and was a founder of the Flaming Faggots and the Effeminists. He is the curator of the photo exhibit, “Gay Liberation Front (1969-1971): A 40th Anniversary Retrospective,” which has been mounted in New York and Las Vegas.