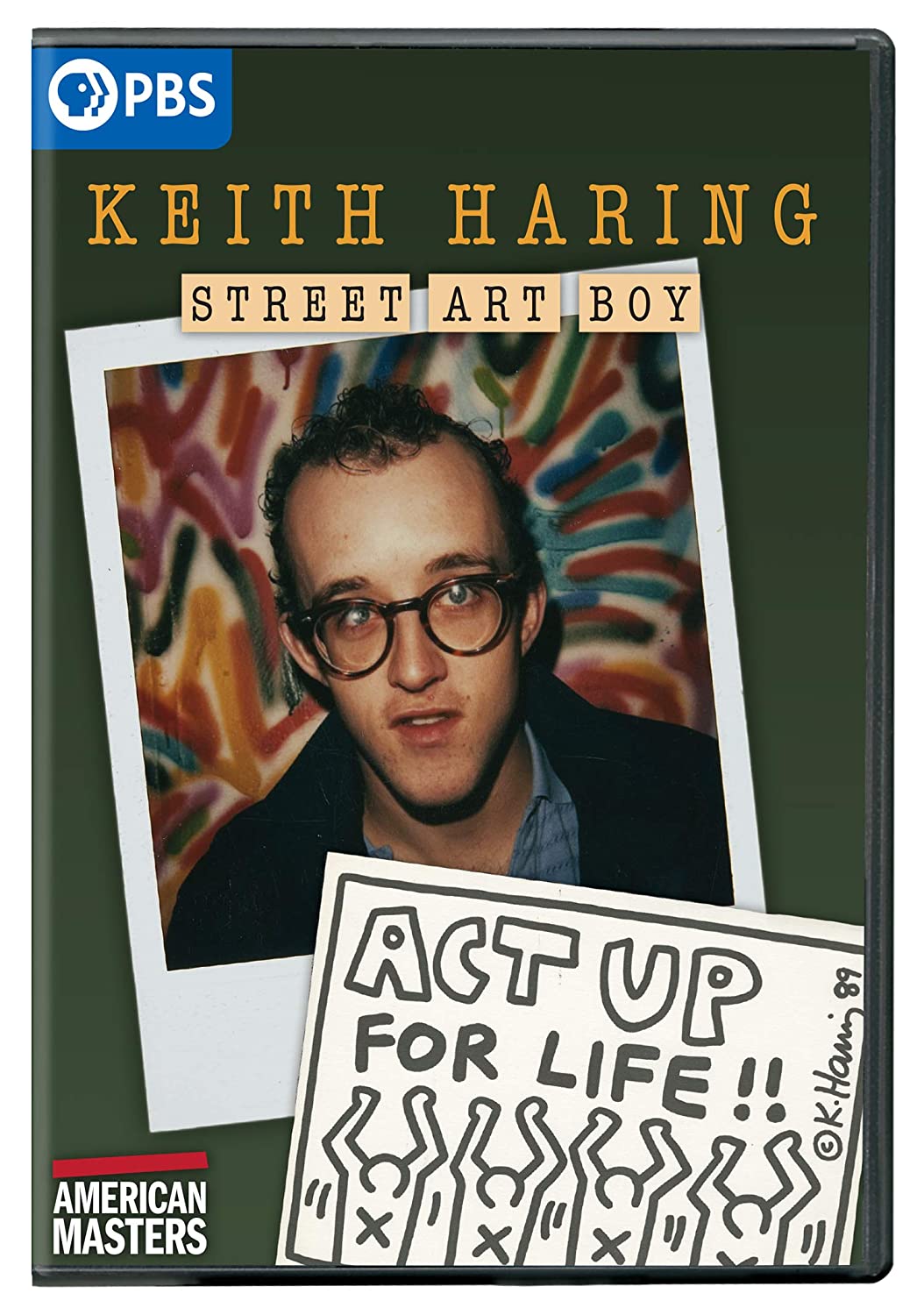

A NEW DOCUMENTARY about the life of Keith Haring culminates in a scene at Christie’s, where an auction is in progress for one of his paintings and a bidding war erupts that ends with a $4 million sale, signaling his arrival into the art establishment. This is going to be a rags-to-riches story about Haring’s meteoric rise from painting free street-art murals to being paid large sums for his art.

No doubt he was driven by commercial success and fame—as Keith Haring: Street Art Boy often reminds us—following Andy Warhol’s example and mentorship. Haring indulged in the tactility of cash, brandishing wads of money that he’d take from a backpack, handing it out to people. However, for those who appreciate his work, especially activists in the LGBT community, Haring’s achievements are measured not by the commodification of his art but by its representation of social issues of importance to this community. Most of his artwork portrays unequivocal imagery addressing issues such as AIDS, apartheid, income inequality, climate change, and our growing dependence on technology. To this end, his artwork is often accompanied by text, such as “Act Up for Life,” “Ignorance = Fear,” “Silence = Death,” or “Crack is Whack.”

Haring was fascinated by the subterranean life within the intricate New York City subway system, and it served him on several levels. First, thousands of people could view his primitivistic, white chalk drawings created almost instantly on empty, black advertising spaces on the walls of subway platforms. Second, the subway was part of a gay male subculture of anonymous sex in tearooms. In the Prince Street subway station tearoom he masturbated with poet and performance artist John Giorno, who wrote about it in his book You Got to Burn to Shine: New and Selected Writings: “We had intense sex, almost a love affair, for over an hour, a long time for subway sex on the run.”

Haring was fascinated by the subterranean life within the intricate New York City subway system, and it served him on several levels. First, thousands of people could view his primitivistic, white chalk drawings created almost instantly on empty, black advertising spaces on the walls of subway platforms. Second, the subway was part of a gay male subculture of anonymous sex in tearooms. In the Prince Street subway station tearoom he masturbated with poet and performance artist John Giorno, who wrote about it in his book You Got to Burn to Shine: New and Selected Writings: “We had intense sex, almost a love affair, for over an hour, a long time for subway sex on the run.”

His chalk drawings were also created on the run—often before onlookers—and was seen by an audience that may not ordinarily go to museums or galleries. He believed that art should be accessible to everyone, so he had a democratizing mission. But he was also thrilled and energized by the edginess of the subway graffiti performance. In a 1989 Rolling Stone interview with David Sheff, he said: “It was this chalk-white-fragile thing in the middle of all this power and tension and violence that the subway was. People were completely enthralled.” In the documentary, a scene is played out on a subway platform when a white-haired older woman incredulously questions Haring about his subway chalk drawings: “What are you doing it for?” He answers: “For everybody, I guess. I don’t get paid to do it. I do it down here so lots of people can see it.” He hands her a keepsake of their brief exchange—a white button with a line drawing of his iconic barking dog.

In one scene in the documentary, the artist’s father, Allen Haring, removes from a cellophane sleeve a hand-written note written when Haring was an eight-year-old third grader. It reads: “When I grow up I’d like to be an artist in France. The reason is because I like to draw. I would get my money from the pictures I would sell. I hope I would be one.” The Manhattan districts of New York City—Alphabet City, the Lower East Side, and SoHo—rather than France is where he ended up. That is where he became an artist, and also where he sought men for sex during the dizzying era before AIDS. When he left his hometown of Kutztown, Pennsylvania, his father had said: “It worried us that he’d be exposed to things we try to protect children from.”

When Haring arrived in New York in 1978, the gentrification of Lower Manhattan’s predominantly Eastern European immigrant neighborhoods had begun. Artists, poets, writers, and radicals rented dirt-cheap apartments in tenements, painting the buildings with fluorescent Day-Glo colors in psychedelic patterns. These below-14th-Street neighborhoods were the epicenter of a countercultural force that challenged the uptown social hierarchy with underground newspapers and magazines, experimental films, dance, performance art, and theater, not to mention the conversion of storefronts into gallery spaces and venues for poetry readings.

Haring took to this urban landscape, and he plunged headlong into the practices and methodologies of street art. He felt a kinship with graffiti artists who spray-painted cartoonish drawings, tagged bold textual calligraphies, and stenciled pictographs, all of which were ubiquitous in New York in the 1970s and ’80s, covering the walls of abandoned buildings and rooftops, subways cars, and train stations. He felt an affinity for this “pop-cartoon sensibility,” as he called it, which aligned with his regard for Walt Disney and Andy Warhol. He understood the political power of street art and celebrated the performativity of the creative process. Sometimes young people break-danced on sidewalks to accompany his mural painting. After dark, he was immersed in the queer subculture of clubs and discos (Mudd Club and Paradise Garage) and bathhouses (Club Baths and St. Marks Place). It was at St. Marks that he met his first boyfriend, Juan Dubose, of whom he said: “He’s the right person. He’s black. He’s really thin. He’s the same size as me.”

Haring didn’t eschew making money and understood the commercial imperative that artists face. In 1986, he opened the Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in SoHo, which sold stuff imprinted with his most familiar iconography, such as coloring books, decals, key-rings, magnets, prints, puzzles, T-shirts, floor-to-ceiling murals, and wall tiles. He wrote this in his journal (as published in 2010’s Keith Haring Journals): “Some ‘artists’ think they are ‘pure’ and outside of the ‘commercialization’ of pop culture, because they don’t do advertising or create products specifically for a mass market. But they sell things in galleries and have ‘dealers’ who manipulate them and their work the same way.” For Haring, what mattered most about the Pop Shop was affordability and availability—art for everyone.

Social activism was pivotal for Haring from early in his life. His childhood friend Kermit Oswald remembered him this way: “Keith, as long as I knew him, was an activist. When Nixon became president, we found ourselves running around town with bars of soap, putting stuff about Nixon on buildings. In Kutztown people didn’t write on things that didn’t belong to them.” His sexual orientation was a crucial part of his identity, and he wrote in his journal: “I’m glad I’m different. I’m proud to be gay. I’m proud to have friends and lovers of every color.” He was profoundly aware of his outsider status, which he provocatively displayed. He flaunted the law not only as a gay man who engaged in public sex but also as an artist who created subway graffiti, for which he was arrested several times on charges of defacing public property. Ultimately he would endure the stigma of being a person living with AIDS.

THE DOCUMENTARY Keith Haring: Street Art Boy, directed by Ben Anthony, takes the formulaic, rags-to-riches narrative and runs with it. Queer sexuality, which was fundamental to Haring’s æsthetic and to his iconographic vocabulary, is completely missing from the film. All phallic imagery—even the mere shadow or hint of it—is erased, even though it was utterly central to his art. There’s no mention or glimpse of his final, major work: a large-scale mural painted in 1989, the year before his death at age 31. Once Upon A Time is a mural across four interior walls above the white porcelain tiles and urinals of the second-floor men’s room in New York City’s LGBT Center. The mural is an end-of-life manifesto. Haring understood the importance of site specificity and the politics of setting, so it’s no surprise he chose an institutional bathroom for a mural depicting gay-male sexuality. It recapitulates public sex in a public space.

While it may be understandable that PBS would ignore explicit sexual images, the documentary also sidesteps any in-depth analysis of Haring’s æsthetic or his social activism, which were at the intersection of queer sexuality and desire, postcolonial dynamics and white supremacy, and the AIDS pandemic with its annihilating experience of loss and abandonment. Also surprising in this era of reckoning about white supremacy is the fact that race isn’t considered at all in the documentary, especially in light of concerns about Haring’s relationship to the issue of race in his life and work. These concerns include his cross-racial sexual attraction, his depiction of people of color as subjects, and allegations of cultural appropriation.

In 1984, Haring painted choreographer and dancer Bill T. Jones’ naked body in white acrylic paint from his head to the tip of his foreskin during a four-hour session that was famously photographed by Tseng Kwong Chi. The performance was widely criticized for being racially exploitative. However, Jones said that he “never felt exploited by Keith” and considered him a generous and loyal friend, a fellow artist with whom he collaborated on dance recitals at The Kitchen, a SoHo performance space. Haring liked the medium of body painting and also covered the nude body of Jamaican model and singer Grace Jones. The session was commissioned by Andy Warhol for Interview and was photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe in his studio. And he painted himself for a photo shoot with Annie Leibovitz. Of the session she wrote in her book Annie Leibovitz at Work: “It’s hard to paint yourself. Keith did only the front. I loved the way he painted his penis. It was so witty with an elongated line.”

These controversies followed Haring even when he went global with one-person shows and commissions in Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. When he went to Australia in 1984, he painted several murals—one in the foyer of the Sydney’s Art Gallery of New South Wales that survived for about a month before it was painted over; and two in Melbourne, including Water Window Mural at the National Gallery of Victoria that developed into a bitter dispute about his alleged cultural appropriation of Aboriginal art. Haring was incredulous about the accusation and said in John Gruen’s book Keith Haring: The Authorized Biography: “When the mural was finished, front-page stories begin to appear in the Melbourne press, stating how insulting it was that I, an American artist, had been hired to come to Australia to make Aboriginal art. I didn’t even know what Aboriginal art was!” Two months later, an unidentifiable projectile, perhaps a piece of concrete or a rock, shattered the central panel, and the entire nine-panel glass mural was taken down.

When Michael Stewart, a young, black artist, was killed by New York City Transit Police after tagging a wall in an East Village subway station, Jean-Michel Basquiat painted The Death of Michael Stewart, also known as Defacement, on a wall in Haring’s studio. Haring wrote about police brutality: “Today I read in the New York Times that all of the officers who killed Michael Stewart were again dismissed of charges. Continually dismissed, but in their minds they will never forget. They know they killed him. They will never forget his screams, his face, his blood. They must live with that forever.” He removed the Basquiat painting from the wall and framed it to be hung over his bed.

It is essential to consider what Haring actually wrote about race. He considered himself to be an unequivocal antiracist and wrote: “Most white men are evil. The white man has always used religion as the tool to fulfill his greed and power-hungry aggression. All stories of white men’s ‘expansion’ and ‘colonization’ and ‘domination’ are filled with horrific details of the abuse of power and the misuse of people.” The colonization of black male bodies in paintings and photographs made by gay white men dates from at least the 19th century, including work by F. Holland Day, George Dureau, Peter Hujar, Touko Valio Laaksonen (Tom of Finland), Robert Mapplethorpe, John Singer Sargent, and Carl Van Vechten, to name a few. Notwithstanding their generally antiracist views, it is fitting that all representations of people of color be scrutinized for possible racial stereotypes.

Haring was acutely mindful of his mortality and was resolute not be defined by it. He wrote: “I’ve never had any sort of delusions about living to when I was an old person. There’re works that I’ve created that are going to stay here forever. … The work is going to live on long past when I’m going to be here.” “Once upon a time” is a stock phrase that begins fairytales, and “They all lived happily ever after” ends them. In a concluding scene from the documentary, fellow artist and friend Kenny Scharf movingly holds a framed drawing of a single, crawling baby that was Haring’s signature tag—this one made by a noticeably unsteady hand—his last image. In Haring’s fairy tale, he draws ever after to the end, nonstop and unstoppable. While he didn’t become an artist living in France, his friend Yoko Ono brought his ashes to Paris, depositing them near the Obelisk at the Place Vendôme.

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, documentarian, and writer for more than fifty years.

Discussion1 Comment

Hi Steven. Thanks for your review. Just so you are aware, the original 90 minute cut of the film, shown on BBC Television – and available to watch here:

https://vimeo.com/manage/videos/419839172

does feature KH’s sexuality and his explicitly sexual work including his amazing ‘Once Upon A Time’ mural. The co-production partner PBS, would not allow any phallic imagery or overt sexual references, in their version of the film. In the BBC version, there is also a section about his work with with Bill T Jones – including an interview with Bill and images of the painting of Bill’s body – as well as a section on the question of Keith and cultural appropriation.

The PBS slot is 1 hour as opposed to 90 minutes, so there will always have to be cuts, but it is regrettable that two absolutely central elements of Keith’s work were omitted in PBS’ cut of the film. Best wishes. Ben