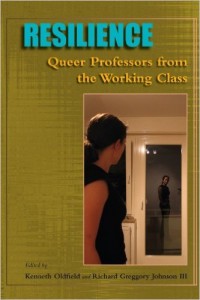

Resilience: Queer Professors from the Working Class

Resilience: Queer Professors from the Working Class

Edited by Kenneth Oldfield and

Richard Greggory Johnson III

SUNY Press. 254 pages, $27.95

THIS BOOK began, like many good ideas, as a conversation. During a public administration conference in Washington, D.C., Kenneth Oldfield, a straight, white, married emeritus professor in Illinois, and Richard Greggory Johnson III, a gay African-American assistant professor in Vermont “with dreadlocks to die for,” began talking about the ways in which academia, for all its professed liberalism, routinely fails to confront its own prejudice against working-class people, especially those within its ranks. The conversation lasted for some time, and the men eventually found themselves talking about the role that sexual orientation plays in academic culture. An idea for a book and a call for manuscripts followed, and the result is a collection of thirteen moving, beautifully written autobiographical essays, each charting a unique, usually roundabout path from working class conditions to the professoriate. The idea for the book’s title, the editors tell us, came from the observation that all of the writers in the anthology “triumphed over incredible odds to become academics.” Indeed, the book’s introduction (and the marketing blurb on the back cover) casts these scholars as so many poster children for the victory of intellectual gumption in the face of societal adversity—a sort of higher ed version of Edward James Olmos in Stand and Deliver.

Fortunately, the essays themselves are more complex and nuanced than the book’s rather clinical introduction might portend. The writers represented include a roughly equal number of lesbians and gay men, from both urban and rural working-class backgrounds, who collectively (and sometimes individually) have studied or taught at nearly every kind of institution of higher learning, from two-year community colleges to elite research universities. The essays have been well edited for length and readability, and they could easily be excerpted for the college classroom or for faculty training. Taken together, these personal narratives show the myriad ways in which economic class, sexual orientation, gender, geography, and religious background effectively isolate and marginalize many would-be academics—although, it must be pointed out, not each in the same way. On the strength of this last point alone, this book should be required reading for any college teacher or administrator interested in promoting (beyond the usual lip service) student diversity.

Two things quickly become clear after reading the essays. First, for working-class students, a consciousness of class is usually learned and internalized much earlier than a consciousness of homophobia, and its effects linger long after sexual identity ceases to be an issue. Second, the academy is generally less comfortable dealing with its own class prejudice than with homophobia. There are the usual, mundane examples of academic hauteur, like department parties where everyone is presumed to appreciate the different kinds of red wine. In one of the essays, Andrea Lehrermeier (a pseudonym), now an associate professor at a large urban university, recalls a graduate student who, knowing only that Lehrermeier had a doctorate from an Ivy League school, insisted on calling rural people “hicks.” She smiled and responded directly: “You realize I come from rednecks, that my folks have eighth grade educations.” The graduate student, embarrassed or at a loss for words, simply fled.

Such anecdotes are wonderfully illustrative, though many of the examples in the anthology are not as cut-and-dried. Timothy Quain, an English professor at a historically black college in Tennessee, poignantly recounts his efforts to add sexual orientation to the college’s nondiscrimination policy—so far unsuccessfully, even as the college has created a very supportive environment for working-class students. Perhaps the most unexpected fact to emerge from the essays is the extent to which notoriously conservative institutions have unwittingly helped pave the way for a queer, working-class professoriate. Almost every essay recalls a moment when a conservative organization provided critical support, whether free foreign language training in the army or a free college preparatory education in a Catholic seminary. In one of the anthology’s highlights, Angelia Wilson remembers preparing for a Rotary scholarship interview in rural Texas. She had chosen a simple, salmon-colored outfit, but the local Rotarians intervened, subjecting her to a complete makeover that included “1988 ‘helmet’ hair, shoes matching my shirt and bag, conservative jewelry, talons, and Hollywood makeup—a kind of ‘nice preacher’s daughter becomes Sue Ellen from Dallas.’”

Wilson could have walked away from such overt diplays of sexism and social fashioning. She didn’t, and she ended up winning the scholarship to attend graduate school in England, where she now teaches her progressive brand of political theory to mostly middle-class students—her “congregation,” as she calls them. The point seems to be that, while academia is not the liberal bastion it is often accused of being, it nonetheless contains the seeds for undoing the conservative, elitist principles that it finds so hard to relinquish.

Joseph M. Ortiz, PhD, is an assistant professor of English at SUNY–Brockport.