GEORGE PLATT LYNES

GEORGE PLATT LYNES

The Daring Eye

by Allen Ellenzweig

Oxford Univ. Press. 664 pages, $45.

SOME TIME in the spring of 1949, the gay publisher and museum director Monroe Wheeler gave one of his famous dinner parties at his Park Avenue apartment in New York. Along with the writer Glenway Wescott, Wheeler’s longtime partner, the guest list included three people who would profoundly shape the image of gay men in 20th-century America and Britain. The novelist E. M. Forster, whose Maurice would become one of the most important gay novels when it was published posthumously in 1971, showed up with his partner Bob Buckingham. They were joined by Alfred C. Kinsey, whose monumental study Sexual Behavior in the Human Male had just stunned the world by showing the ubiquity of homosexual behavior. The third documentarian in the group was the photographer George Platt Lynes, who by that time was well known in the art world for his iconic portraits of artists and celebrities.

Although Lynes is usually mentioned in studies of queer Modernism, he is rarely placed in the same category as Paul Cadmus, Christopher Isherwood, or Tennessee Williams—all of whom Lynes knew and photographed. This may change with the publication of Allen Ellenzweig’s George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye, a sumptuous biography that makes a compelling case for Lynes as an important actor in the history of queer representation. Just as Cadmus, Isherwood, and Williams infused their works with a gay sensibility that was perceptible to gay audiences, Lynes’ photographic portraits of his gay friends managed to intimate their desires and relationships without publicly scandalizing anyone. As Ellenzweig puts it, Lynes’ “continually expanding assembly of portraits made for documentary evidence … that there was a flourishing gay life in which they all took part.”

As a boy, Lynes did not show much promise as a creative force. Despite being sent to good private schools from the age of eleven, he was easily bored with academics and struggled in his classes. He also had a habit of discomfiting his male teachers, who commented awkwardly on his “kittenish” behavior and “rather more than friendly skirmishing” with his male classmates. This coquettish personality would prove to be a social asset when Lynes was older, but at sixteen it perturbed his parents, who worried that he wasn’t “manly” enough to fit in with the other boys. One of his high school classmates was Lincoln Kirstein, who would later be a valuable professional contact for Lynes as cofounder of the New York City Ballet. The teenage Kirstein, however, had little patience for the effete Lynes, whom he dismissed as “a sneering little bitch.” Ellenzweig surmises that Kirstein, who was also gay, may have been projecting his own insecurities onto the “foppish” Lynes.

The course of Lynes’ life changed when he took a trip to Paris in 1925. Paris in the 1920s was both a bastion of artistic experimentation and a haven for sexual freedom, and the eighteen-year-old Lynes eagerly took advantage of both. He soon found his way to the mecca of the queer Modernist sensibility: the salon of Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. The notoriously selective Stein was charmed by Lynes—“Baby George,” she affectionately called him—and admitted him into her circle of predominantly gay and bisexual artists. It was largely through this circle that Lynes met (and in some cases had sex with) some of the most exciting new talents of the day, such as composer Virgil Thomson, Russian painter Pavel Tchelitchew, surrealist poet René Crevel, and avant-garde polymath Jean Cocteau.

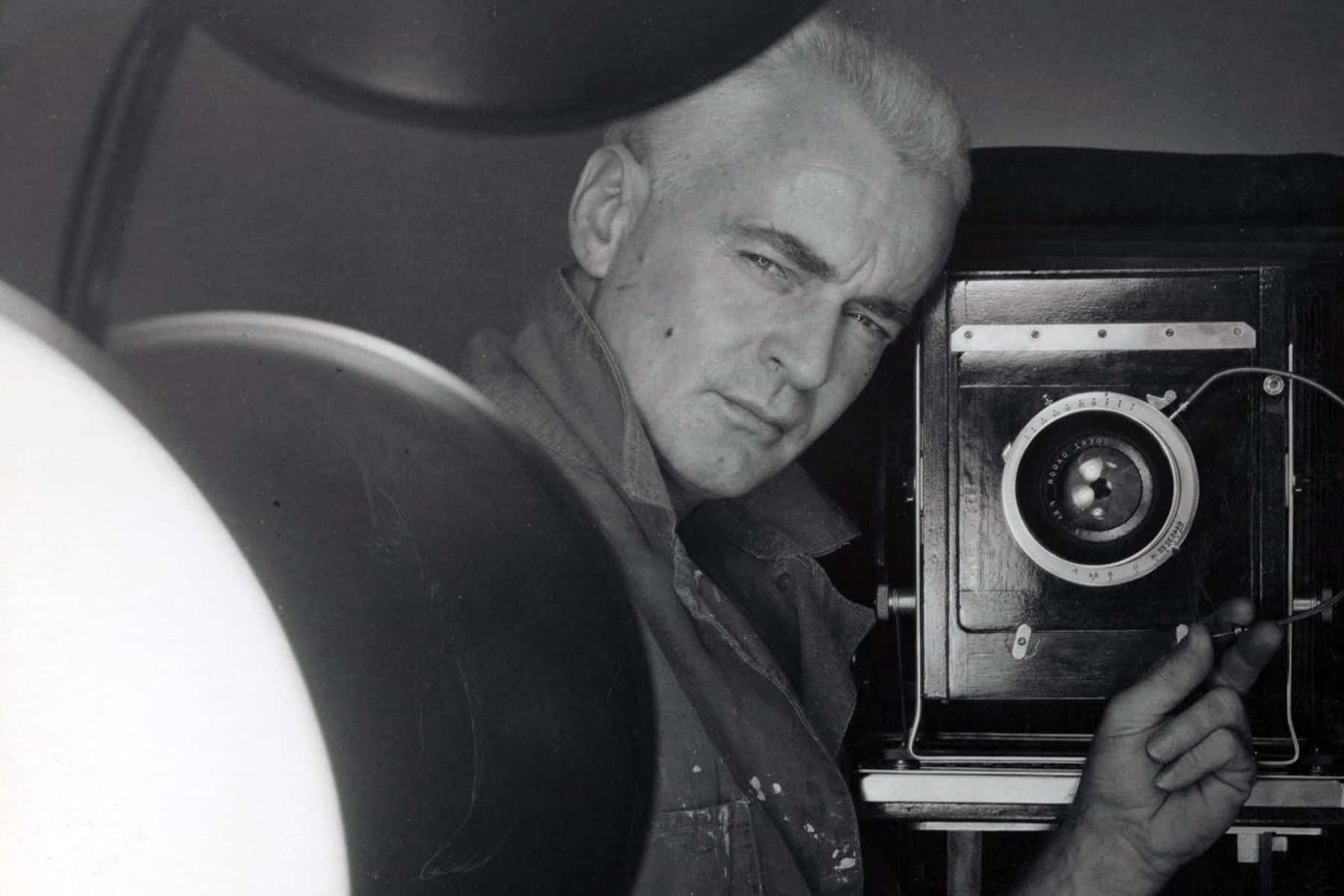

Lynes convinced these artists (including Stein) to be photographed, ostensibly on a whim. But the resulting portraits were far more dramatic and unexpected than the snapshots of a typical fanboy. The photo of Stein was especially surprising, Ellenzweig explains, for the way it took the mythic Stein and made her appear “available to the world at large.” This combination of familiarity and unexpectedness is a trademark of Lynes’ most famous celebrity photographs, and it explains why they became so iconic. Lynes had originally planned to be a writer, but his friends, noticing his talent, urged him to consider photography as a career. When he eventually took up the suggestion, he found the work—and the access to important people that it provided—both profitable and addictive. As he put it: “I want now to photograph as many well-known and conspicuously beautiful people as possible.”

The two most important people that Lynes met through his Stein connections were Wheeler and Wescott. Fittingly, his first impression of Wheeler was from a photograph that he stumbled upon when meeting Wescott for the first time in the writer’s New York hotel room. The twenty-year-old Lynes let out a whistle and said: “That’s the man for me.” Thus began a romantic, and frequently tumultuous, three-way relationship that lasted for the next sixteen years. As one might expect, negotiating such a triangle was complicated, not only because Wheeler and Wescott had already been together for several years but also because Lynes was much more sexually attracted to Wheeler than to Wescott. In many ways, the Lynes-Wheeler-Wescott saga is the emotional core of The Daring Eye. Ellenzweig is an empathetic biographer here, and he beautifully captures the perspectives of all three men over the course of their relationship. He is helped by Lynes, who wrote extensively about both men in his letters and diaries, often in code. For example, when he had sex with Wheeler or Wescott, in his diary he would draw stars by their names or draw the initial “M” or “G” inside a circle.

One of the great virtues of Ellenzweig’s sweeping book—it runs over 600 pages—is that it’s as much cultural history as personal biography. Lynes was able to photograph so many luminaries because he moved in their circles, and his evident talent made him a likely collaborator on many of their artistic projects. Ellenzweig provides in-depth accounts of these figures and projects as they came into Lynes’ orbit, from Paul Cadmus’ portraits of Lynes and their friends, to Kirstein’s establishment of the New York City Ballet under Balanchine, and to the dazzling premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts. In this respect The Daring Eye follows the model of Martin Duberman’s The Worlds of Lincoln Kirstein and Jerry Rosco’s Glenway Wescott Personally, two biographies of Lynes’ friends that show the extent to which 20th-century American art was driven by a transatlantic circle of gay friends and lovers.

Another selling point is Lynes’ photography itself, which Ellenzweig always keeps in focus. At the same time that he was producing celebrity portraits for magazines and gallery exhibitions, he was creating male nudes that were just as insightful and intriguing. Lynes typically showed his nudes only to close friends, though he did give some to Kinsey, who was keenly interested in homoerotic images. He also submitted a few (under a pseudonym) to the Swiss homophile magazine Der Kreis. Ellenzweig discusses Lynes’ nudes together with his public photos and gives a fuller picture of Lynes’ æsthetic development. While Ellenzweig’s adept, enticing descriptions of specific photos frequently had me surfing the Web for a copy, the book itself offers a large number of photographs. Some of these images, like Actaeon, will be familiar to many readers, while others, such as Man in His Element, a tenderly erotic photograph of an interracial couple, may be a revelation. Ellenzweig’s splendid biography shows more thoroughly than ever before the full range of his talent.

Joseph M. Ortiz’s new book, Imperfect Freedom: Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel, is forthcoming from Lexington Books.

Discussion1 Comment

Whether Mr. Ortiz simply wrongly extrapolated from page 427 of the book—“When Monroe invited George and [his mother] Adelaide Lynes to pre-dinner cocktails so they might meet E. M. Forster in the company of Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey . . . .”—or from another misinformed source, Mr. Ellenzweig does not state that Lynes stayed for dinner for, as documented by Forster biographer Wendy Moffat, he did not. “It was a disarming idea to start with George, like an amuse-bouche. He lingered just long enough to persuade [Forster and his married lover Bob Buckingham] to have their portraits taken the following week at his studio. Then the Lyneses evaporated.”

As Moffat also detailed, Wescott wrote in an October 10, 1971, “New York Times” article, “A Dinner, a Talk, A Walk With Forster,” that his and Wheeler’s fourth dinner guest, with Forster, Buckingham, and Kinsey, was “old friend of his and mine, Joseph Campbell, the Sanskrit scholar, who has both professed and written about comparative mythology.” He did not mention Lynes and his mother having been there for cocktails.

As one would expect only two years after Stonewall, Wescott described his co-lover/roommate-with-Lynes Wheeler only as “my best friend,” and Buckingham as Forster’s “friend of long standing, Robert Buckingham, a big, boyish man, a police officer, who (with his wife May) provided a family life when Forster wanted it in his later years.” For those unaware, Buckingham and his wife (who sometimes claimed she didn’t know of her husband’s sexual relationship with Forster) named their son after Forster as did another of his lovers.