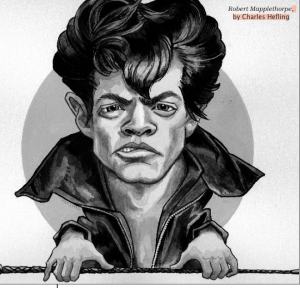

IN PURELY VISUAL TERMS, they appeared to be an odd couple. With his exceptionally handsome face etched deeply with a desirable masculine divinity, and held gracefully atop a tall, impeccably dressed build, Sam Wagstaff exuded sophistication, taste, education, old money, and confidence, while his slim younger partner, dressed rebelliously in denim and silver-studded black leather, seemed vaguely edgy and preoccupied. Robert Mapplethorpe did not appear to fit comfortably among the guests gathered at a cocktail party on Gramercy Park East that early fall evening of 1975, and gave the slightest impression that he’d rather be elsewhere.

As the hostess was a longtime friend of my former lover and me, she had invited us together, as we were at that time attempting what proved to be an unsuccessful reconciliation after a summer breakup. But having spent a few months as a single 26-year-old gay man, I’d learned to stretch my wings and liked the freedom. So my senses were equally though discreetly attuned toward men I found attractive, funny, and interesting.

As the hostess was a longtime friend of my former lover and me, she had invited us together, as we were at that time attempting what proved to be an unsuccessful reconciliation after a summer breakup. But having spent a few months as a single 26-year-old gay man, I’d learned to stretch my wings and liked the freedom. So my senses were equally though discreetly attuned toward men I found attractive, funny, and interesting.

Robert Mapplethorpe and I shared a few words of introduction, but I felt no particular connection with him. Frankly, his sartorial appearance indicated a preference for a kinkier kind of sexuality than interested me at the time.