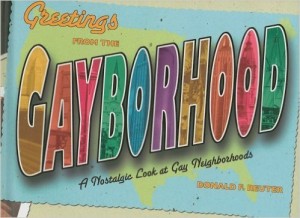

Greetings from the Gayborhood

Greetings from the Gayborhood

by Donald F. Reuter

Abrams Image. 114 pages, $19.95

IN A POEM called “The Dump,” one of the last published by the late Thom Gunn, he describes a dream in which he wanders around a lifetime’s worth of ephemera left behind by a departed friend and fellow author. He sees vast mounds of paper, collections of every note and draft and manuscript the writer ever produced. But he also peruses the more common refuse of the man’s life: “I went in further and saw/ a hill of match covers / from every bar or restaurant/ he’d ever entered.” I thought of this poem as I read Donald F. Reuter’s Greetings from the Gayborhood, because Reuter’s book is like a collective photo album of gay American life since the mid-1940’s, and it’s lavishly and lovingly illustrated with the kinds of images one could imagine filling the landscape of Gunn’s poem.

The book is designed to mimic the horizontal layout of a postcard or a small photo album, and it appropriates the visual elements of the traditional “Greetings from …” postcard as a unifying design concept for what Reuter describes as his “whirlwind tour of twelve gayborhoods.”

This is the term that Reuter uses to single out those urban areas “where we gay people are—or appear to be—the majority of visitors and residents.” It should also be noted that Reuter is really talking only about gay male neighborhoods. He acknowledges that an array of social, economic, and other factors have contributed to both the formation, and the dissolution, of the gay enclaves his book describes. And because these transformations have already altered many of the places he highlights, there’s a sense of that wistful, “wasn’t it great when …” feeling in Gayborhood.

Reuter has clearly done a lot of searching through the archives of local libraries, history museums, and gay and lesbian centers across the country. The book’s illustrations include images of matchbooks, postcards, newspaper ads, coasters, club and bathhouse membership cards, and similar objects, but also personal snapshots of gay men in bars, at parties, pride parades, and so on. The result is a book that, despite its small scale, offers a representative slice of the personal side of gay history in the pictures of the men who lived it. Knowing that AIDS has claimed so many lives since the 1980’s, forever changing the face of many “gayborhoods,” many of the book’s images have a poignancy about them. But Gayborhood is above all a celebration of gay lifestyles, and its wealth of images is sure to provoke happy memories as well as bittersweet ones.

The brief narrative accompanying the book’s illustrations is written in the form of a tour of gay life  in American cities, circa 1978, inspired by the popular gay guide, Bob Damron’s Address Book. This follows an introduction that provides some historical context for the tour. A book this size can’t pretend to be a scholarly history of its subject, but Reuter’s brief overview manages at least to summarize the demographic and sociological forces that helped give birth to, cultivate, and ultimately transform the queer spaces of America’s major cities.

in American cities, circa 1978, inspired by the popular gay guide, Bob Damron’s Address Book. This follows an introduction that provides some historical context for the tour. A book this size can’t pretend to be a scholarly history of its subject, but Reuter’s brief overview manages at least to summarize the demographic and sociological forces that helped give birth to, cultivate, and ultimately transform the queer spaces of America’s major cities.

Of course, one factor leading gays to congregate in America’s urban centers is the fact that cities have always been the adult playground; but Reuter also stresses that, as the middle class moved to the suburbs in the mid-20th century, many single men (in particular, those fresh from stints in the service) moved in to the cities. Reuter charts six major phases in the growth of gay neighborhoods, from 1946 to the present: “That’s Entertainment,” 1946–58; “Present, but Unseen,” 1959–68; “The Golden Age,” 1969–78; “The Poster Boy,” 1979–88; “Gay is Good,” 1989–98; and “Seeing the Forest for the Bush,” 1999–present. Before beginning the tour, he also cites some of the identifying characteristics of the typical gayborhood. These include their relative compactness, their tendency to develop in places once considered “the wrong side of the tracks,” and the presence of porn shops or other venues featuring displays of male allure. In addition, each gayborhood has its “promenade,” some stretch along the main drag where residents and visitors can parade in all their finery.

Locals will no doubt lament the many details that the book misses about their home city, but Reuter does a fine job of capturing the broad history and texture of the places he visits. He’s clearly done his homework not only in researching the images, but also in talking to the locals and getting a sense of what each gayborhood was, and is, all about.

A book such as this that attempts to offer a representative cross-section of gay life in America will undoubtedly receive criticism for which cities were included and which were left out. For example, Fort Lauderdale makes the cut but not Miami. Reuter explains that his aim is to include “distinctly American” gay enclaves, while Miami has a more international flavor, and it’s such a mainstream draw that it doesn’t have a well-defined queer area. The explanation isn’t likely to appease the boys in South Beach, but he makes a strong case for this choice. Other cities, like New York and Los Angeles, comprised of multiple gayborhoods, almost deserve their own books. Still, Gayborhood is a visually rich and entertaining introduction to these and other U.S. cities.