Published in: September-October 2008 issue.

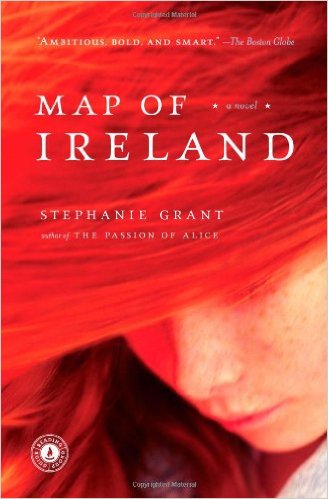

Map of Ireland

Map of Ireland

by Stephanie Grant

Scribner. 197 pages, $22.

IF YOU LIKED the film Juno and its wise-cracking teen heroine, you’ll enjoy Ann Ahern, the teen protagonist in Stephanie Grant’s new novel. Map of Ireland is a story about a lesbian teen from South Boston and the things she learns about prejudice and love in 1974, the first year of the city’s school busing program to mix students from segregated neighborhoods. While she’s ashamed of the white mothers who alternately throw rocks and pray in front of her school—and also of George Wallace, who comes in a wheelchair to show his solidarity—she learns that racism runs deep, spawned by ignorance in others and in oneself.