The Beautiful Tendons: Uncollected Queer Poems, 1969 – 2007

The Beautiful Tendons: Uncollected Queer Poems, 1969 – 2007

by Jeffrey Beam

White Crane Books. 143 pages, $14.95

This book gathers the homoerotic poems written by Jeffrey Beam over the past thirty years. Included are about 75 poems which have appeared in widely scattered small press magazines but not his poetry chapbooks. The poems are linked by the topic of male love and friendship. An unrelenting intelligence drives Beam’s poems toward an agenda that’s mystical, sexual, and pantheist. He is one the wild children of Whitman, whom he quotes frequently. Like Whitman, he celebrates those moments when sexual interest between men is recognized, signaled, and secured. Passionate and wistful, these are poems about the spirit of love and the mysteries of affection, not of sexual consummation. “A Man Mutilated By Desire,” written in the manner of Cesar Vallejo, demonstrates Beam’s ability to replicate poems of any type or style. Meanwhile, in poems such as the one that lends the book its title, Beam’s own style—precise, pared down—moves images and ideas along in ways that consistently surprise and delight. The seven terse lines of “I Fell In Love With” rise to the level of Chinese masters as they skillfully build around his tree metaphor to capture the one thing about love there is to regret: its brevity. “Love Comes” takes off on a famous Creeley poem (“Love Comes Quietly”) to make precisely the opposite point: that love’s arrival is often anything but quiet, and certainly no quieter than the arrival of a new season. The success of these poems derives from Beam’s consistent focus on developing a thought and allowing us to watch it move, grow, and die without embellishment or gimmickry. Beam is that rare poet who explores depth and complexity while taking evident satisfaction in making himself understood.

Jim Cory

Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited

Chronicle of a Plague, Revisited

by Andrew Holleran

DaCapo Press. 304 pages, $16.

Several months ago, Andrew Holleran was in a library browsing books about AIDS, and he came upon his own book, 1989’s Ground Zero, collecting dust. It’s never easy for an author to know that his work is out of print, notes Holleran, especially when its subject is still relevant. Despite medical advances and preventative measures, people are still getting infected and dying of HIV. Friends urged him to republish Ground Zero, and an editor agreed. The resulting book gathers the original 23 essays along with ten others that appeared in Christopher Street, plus a new introduction. Back in the 80’s, it was hard to believe that everyone went about their lives as the AIDS virus took hold in the gay community. Denial was rampant: seeing 25-year-old men shuffle along as if their bones were decades older wasn’t enough to convince some people. Lesions on legs, gaunt faces on formerly exuberant people, funerals that brought friends back to New York, were more common still. And yet, life went on as if a cure were near. Holleran writes about a plague that classified men as “negative” or “positive.” He tells of friends who died alone, others who went out loudly and publicly; the irony of bringing a Life magazine to a dying man; the weariness of attending yet another funeral; the astonishment of men who knowingly carried the virus but didn’t tell potential sex partners. The fact that many of these essays were written some years ago, and all are set in New York, might make it hard for some readers to relate, but the emotions they capture make it a universal drama—a cautionary tale and an unsettling look at how far we haven’t come.

Terri Schlichenmeyer

Swish: My Quest to Become the Gayest Person Ever

Swish: My Quest to Become the Gayest Person Ever

by Joel Derfner

Broadway. 272 pages, $23.95

The title and subtitle of Joel Derfner’s new book would lead one to believe that Swish is a frivolous and juvenile collection of writings chronicling, say, the stereotypical misadventures of a vapid gay life. Lies! The book is instead a series of well-written essays that, while initially appearing as light-hearted and comic blunderings in the daily life of a gay man, quickly morphs into intelligently thought-out and often deeply moving explorations of what it means to be alive. Each chapter is also brilliantly witty. An essay on go-go dancing, for example, becomes an exploration of self-image and how the appearance of a change in one’s status, while leaving the person unchanged, can transform him in the eyes of others. Derfner gets all this from dancing on a bar in his underwear. Stories about summer camp, cheerleading, and knitting receive similar treatment. In addition, the book contains carefully crafted prose which every now and then lobs a bit of vocabulary at you that momentarily strips you of any pretense you have to English literacy—words like “tatterdemalion” (one in tattered clothes, a ragamuffin). Unless you’re looking for a reading experience that will make you laugh, choke up, and think about your humanity, I strongly recommend that you keep your distance.

David Pasteelnick

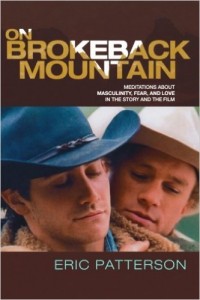

On Brokeback Mountain: Meditations about

On Brokeback Mountain: Meditations about

Masculinity, Fear, and Love in the Story and the Film

by Eric Patterson

Lexington Books. 386 pages,

$39.95 (paper)

With his ode to Brokeback Mountain, Eric Patterson has created an exhaustive but reader-friendly examination of the short story and the film adaptation. Particularly intriguing is his prologue, “Reactions to Brokeback Mountain,” which paints a rather uncomfortable picture of just how negatively many in the mainstream media and Hollywood responded to the prospect of a film about two queer cowboys. (Especially bizarre is a quote from Oscar-winner Ernest Borgnine, clearly aghast by the film’s implications: “If John Wayne were alive, he’d be rolling over in his grave.”) Patterson situates much of his arguments around what Brokeback did in terms of the genre of the Western, stereotypes, and how the story relates to the work of Walt Whitman, among others. It’s undoubtedly a valid treatment, and Brokeback fans will want to read this thorough analysis. But this treatment is very much a literary one, and the student of film studies in me would have liked a broader approach to the Brokeback phenomenon. There’s no real analysis of audience and critical response to the film or the fact that in some circles it re-ignited many of the arguments that critic Vito Russo (The Celluloid Closet) made so powerfully about gay imagery and Hollywood’s homophobia. Also, an analysis of the fact that both of the lead actors in Brokeback (Jake Gyllenhaal and the late Heath Ledger) went out of their way to assert their off-screen heterosexuality made clear just how far Hollywood has not come over the years. Still, Patterson’s book is a powerful tribute to the story and the film; the fact that it raises new questions is testimony to our ongoing fascination with Brokeback Mountain and its landmark status.

Matthew Hays