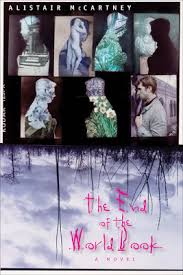

The End of the World Book

The End of the World Book

by Alistair McCartney

University of Wisconsin Press. 320 pages, $26.95

AS A KID, I got lost in the 1976 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. Like me and, I assume, many other boys like us, Alistair McCartney spent his youth obsessed with his favorite encyclopedia set, and he has returned to it, as if he’s been haunted by it all these years. It’s a strange, intriguing narrative, mixing fact and fiction, the banal with the apocalyptic, and the nostalgic with the bizarre.

The alphabetically-arranged sections have unassuming names, but some of the entries are stunning in their wit, wisdom, and sharpness. Some are poignant; others are downright disturbing. Take, for example, “Beauty”: “Throughout Western history, philosophers have spent a lot of time contemplating beauty. As they’ve done so, drool has slithered out of the corners of the philosophers’ mouths. … Pretty much what they have come up with is that every encounter with beauty begins very promisingly but inevitably ends in a musty atmosphere of disappointment and a failure to return one’s e-mails and phone calls. As Plato said so fittingly, Beauty is barbaric; beauty must be destroyed.” McCartney is all over the map here, ranging from Classical philosophy to mundane heartbreak (is there any other kind?).

Some of the entries remind us that we have very little sense of who actually writes reference books. McCartney’s personal, subjective voice stands in stark contrast to the bloodless position in the real World Book. The entry on “Hummingbirds” begins: “God, I love hummingbirds! I like how stressed out they are, and how they move their wings so quickly.” There’s nothing in The World Book like that, but maybe there should be. The love of knowledge—and of experience, of loss—is the connective tissue of this novel, which otherwise lacks an overarching theme or even characters, other than the ones who appear in entries like “Corday, Charlotte,” “Umbrella, My Aunt Joan’s,” and “Zero, Patient.”

The “end” part of the title suggests the apocalyptic, which McCartney seems to desire at various points in his novel. Some of that is reflected in his take on the contemporary political climate, some in his frustration with the tedium of the 21st century, and some is just McCartney’s personal world view. The entry, “West, Decline of the” reads: “Back in antiquity, when ruins were brand new, men were the hottest. Since then, historically, beauty has been on a slow and irreversible decline.” Or this one, which elaborates on the novel’s title: “They say that when the world ends, the World Book Encyclopedia will remain intact, and that its twenty-two gold-edged volumes will replace the world.” The World Book Encyclopedia contains the world; McCartney’s novel displays, proudly and provocatively, what his most personal encyclopedia holds.

For readers, this first novel provides us a view into the idiosyncratic mind of someone who has lived at the land’s end for most of his life—in Perth, Western Australia, the world’s most isolated major city, on the verge of the Indian Ocean and the Australian continent, and in Venice, California, on the edge of Los Angeles, of the Pacific, and of North America. The view from there is challenging, disturbing, and engaging. A side-effect of the novel, which is in some ways my favorite part, is that it compels readers to imagine what our personal encyclopedia would hold and wishing that McCartney hadn’t beaten us to the punch with his inventive, satisfying End of the World Book.

____________________________________________________________________

Chris Freeman, who teaches at USC, is co-editor (with James Berg) of Love, West Hollywood: Reflections of Los Angeles (Alyson).