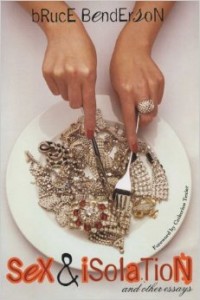

Sex and Isolation and Other Essays

Sex and Isolation and Other Essays

by Bruce Benderson

University of Wisconsin Press. 208 pages, $24.95

BRUCE BENDERSON’S iconoclastic new novel minces no words when it comes to the present state of contemporary culture: he believes a lot of things have changed for the worse. It is Benderson’s contention that a major shift in the culture occurred when virtual reality, or the “on screen” information age, replaced the tactile world of public space. He blames the Internet with its “continuous electronic swaddlings,” which have taken the place of “countless hunts in the streets of midtown New York for sex.”

Consider the case of New York’s Times Square. Once a lively albeit seedy hotbed of adult theaters, porno shops, and hustler and pimp bars, Times Square today could host an Osmond family reunion. The “improved” Times Square can be traced to the good housekeeping obsessions of former Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (“a man with the rigid, down-turned lips of a corpse, whose suits resemble those of an undertaker,” Benderson says), even as the Internet steps into the breach with its alternative modes of gratification.

Benderson’s aptly titled Sex and Isolation is a witty elegy for the way things used to be. He remembers some of the dives he would frequent in Times Square and some of its more interesting characters, and laments the disappearance of “the harsh lights, oversized signs, smell of burning flesh from the hotdog stand, ringed eyes of pallid prostitutes, black-and-white male beefcake magazines, outlines of genitals through the Mod pants of hustlers,” which have been replaced by “theme restaurants, multiplex film complexes, and souvenir stores.”

Meanwhile, the Web’s “unintentional data leaks, schoolboyish terrorist attacks, and chaotic mumblings [are]moving towards a new architectural model of experience.” Benderson ranges across all of popular culture. Here he is on fashion: “Whether we like it or not, fashion remains a way for the poor to invade the sight of the rich with inescapable, aggressive imagery. It is speech that can’t be silenced.” On the American obsession with child protection: “Whereas the necessities of city life invented the independent child, the suburbs reversed this phenomenon and reinvented the late adolescent—and even post-adolescent—as a dependent.” And on why yesterday’s closeted homosexuals didn’t have it so bad: “[It] allowed married men to experience isolated erotic episodes, and still be intensely attracted to women. Sexual impulses are too fragmented to base an entire sociological identity upon, and to brand them simply ‘closeted’ is intolerant and presumptuous.”

In a series of diary and autobiographical segues, Benderson recounts his days as a youthful San Francisco Tenderloin sex worker despite his having grown up as a middle class kid in Syracuse. He recalls the times before the 1970’s as a time where “people existed magically unaccompanied by family members,” when practical activities like shopping or work were less regimented, opening doors for erotic possibilities. America then, he writes, was secretly eccentric: “It had multiple dark corners for misbehavior. It had a bus station where adolescents could experiment with cruising adults. It had large, old-fashioned libraries with unmonitored corners.”

Benderson is a one-man hypocrisy detector, wondering how, for example, we square our rigid age of consent laws and our obsession with child predators with the practice of dressing four-year old girls in feather boas, tiaras, and miniskirts so their ambitious mothers can enter them in “beauty pageants.” He writes with a wit and style that should have even impassive readers grinning or grimacing.

____________________________________________________________________

Thom Nickels is the author of Out in History and Philadelphia Architecture, among other books.