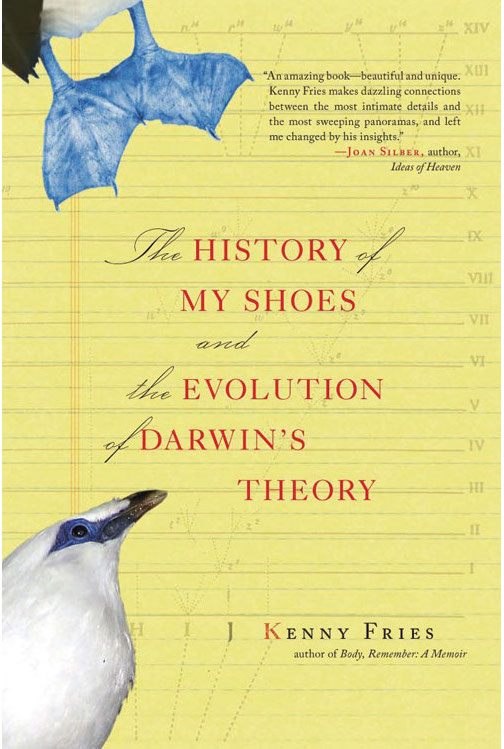

The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory

The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory

by Kenny Fries

Carroll & Graf. 206 pages, $14.95

IT’S TOO BAD that Kenny Fries new book isn’t longer. The History of My Shoes and the Evolution of Darwin’s Theory is so lyrical, economically crafted, and engagingly peripatetic that one wants to keep traveling with its author even after he ends his meditation. Part memoir, part history, part travel narrative, Fries’ book is an extended examination of his unique experience of disability, and it’s presented within the context of broader ideas about humanity’s place within the natural order. Fries has written two well-received books of poetry and an earlier memoir about his disability, but his latest work approaches the subject with a fresh, metaphorically rich perspective.

Fries’ History progresses along two lines. One is a personal account of his acceptance and transcendence of his condition, as well as a narrative of the emergence of his queer identity. The other is a description of Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s nearly simultaneous development of the theory of natural selection. In short, alternating chapters, Fries takes his readers back and forth in time, both within his own life and in the lives of Darwin and Wallace. Like the English scientists he writes of, who painstakingly gathered data from the natural world to carefully build the framework of their theory, Fries mines his own experience and that of the co-developers of evolutionary theory for unique insights into his unusual condition.

Fries brings a literary sensibility to his observations about disability and the history of science that reminds one of the work of Oliver Sacks, particularly Sacks’ own memoir of a brief disability, A Leg to Stand On (1984) and his later book, Island of the Colorblind (1997). Like Sacks, Fries looks at science and nature through a poetic prism. Fries is fond of quoting poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins and Elizabeth Bishop, among others, and his lean prose is richly evocative, particularly when he’s describing the exotic flora and fauna he encounters on his travels.

What’s most affecting in this book is Fries’ ongoing effort to both defy and understand his physical situation. He does his best to push himself beyond his limitations (as in his many hikes and challenging journeys), but he does not leave unconsidered the prejudices he faced when growing up as a disabled child. Not surprisingly, the metaphor of adaptation gets quite a workout in his History, and his unique reliance on his shoes, his most important way of adapting to his condition, is rendered in wonderful detail, with grace and poignancy.

Fries attempts an examination of his sexuality along these lines as well. According to his description of his youthful summer vacations with his family, he was, despite his condition, able to achieve frequent sexual intimacy with both females and males. He clearly prefers the latter, but he admits that he’s unsure of how the categories of sexuality apply to both his early “straight” male partners and to himself. He suggests, without exploring the topic much further, that there might be a more adaptive, amorphous quality to sexuality than most of us are willing to admit. Such an argument seems to carry more authority when offered by someone who is living with a condition that defies medical classification.

One thing that’s certain about Fries’ condition is that it is not static. He notes that his lower extremities continue to change and deteriorate, necessitating new shoes and, eventually, other means for coping with its challenges, new means of adaptation. Fries broadens his exploration of disability in brief discussions of his partner’s struggles with attention deficit disorder, and he offers an intriguing theory of its origins. That we are all forced to contend with such challenges in one form or another is one of the insights offered in this splendid book.

____________________________________________________________________

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to this publication.