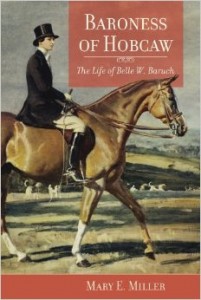

Baroness of Hobcaw: The Life of Belle W. Baruch

Baroness of Hobcaw: The Life of Belle W. Baruch

by Mary E. Miller

Univ. of South Carolina Press. 212 pages, $29.95

THE PRIVILEGED and charmed life of Belle W. Baruch (1899–1964), daughter of Wall Street financier and presidential adviser Bernard M. Baruch, was marked by curious unorthodoxies in temperament and behavior. Looking more like a tall, gawky young man than like a “lady” of her era, Belle’s greatest love was perhaps her father, Bernard, who owned a vast estate in South Carolina that he called Hobcaw Barony, a seaside retreat that included several small islands and all manner of wildlife. It was here that Belle grew up under her father’s wing, and where she came to resemble him, right down to her adoption of his condescending racial attitudes towards Baroney’s black servants. It’s a setting that author Mary E. Miller describes as “almost feudal” and “one of noblesse oblige.”

Bernard Baruch, known by many as “the Wolf of Wall Street,” had close relationships with FDR and Winston Churchill, and advised Truman (who considered him a “meddler”), Eisenhower, and Kennedy. In the 1920’s, Henry Ford was Baruch’s most formidable nemesis. Ford believed that Jews controlled the loan companies, the movie industry, and commodities like sugar, cotton, and grain. Indeed he believed there was a Jewish conspiracy to control the world through an international company whose emissary was—Bernard Baruch. So intense was Ford’s hatred of Baruch that he published his collected diatribes against him in a book. These attacks charged Baruch with being instrumental “in the effort of Judah to control the United States and the world.” At the same time, Baruch was often criticized by fellow Jews for “not being Jewish enough,” as his wife Anne and his daughters were Episcopalians, and Baruch himself attended synagogue only on high holy days. Belle was not a novelist, playwright, or poet; nor did she begin a political movement or run for office. Her fame rests almost entirely on her father’s reputation as the most powerful Jew in America at a time when anti-Semitism was rife. Born into the lap of luxury—on her twenty-first birthday she was given a million dollars—she would go through life able to indulge her every whim. She would also go on to set records in horse jumping in England and America, winning several prestigious awards. The equestrian life brought Belle to Europe, where she socialized with aristocrats and the wealthy. The long trips abroad gave her the opportunity to respond to sexual awakenings that began with her love for her friend Evangeline Brewster Johnson. Evangeline and she had been very close, but Belle didn’t realize she was in love until Evangeline announced her engagement to conductor Leopold Stokowski. Belle tried to be enthusiastic about this engagement but, as Miller writes, “a cold dread was building within her as she struggled to share Evangeline’s happiness.” She eventually came to accept her homosexuality, though she never identified as a lesbian. Her family never referred to her lesbianism but tended to view her female lovers as friends or houseguests. Miller doesn’t say whether Belle objected to this cover-up, or how she reacted to her brother’s intense hatred of her homosexuality. Her cool hauteur, her lengthy European sojourns, and her acceptance by European society helped protect her from base American prejudices. Her life in Europe was a continual round of foxhunts, parties, luncheons, and automobile excursions. But life definitely got more interesting for Belle when she met San Franciscan Barbara Donohoe in France some time in 1928 or ’29. The mutual attraction evolved into a love affair that ended years later when Donohoe returned to San Francisco to comfort her dying father. Unable to resist the influence of her Irish Catholic family, Donohoe fell in love with a man and never saw Belle again. This loss proved devastating for Belle—until she met Alison “Dickie” Leyland. Dickie soon became a permanent part of Belle’s life, living with her at Hobcaw and over time becoming a dominant, albeit negative, force that included years of excessive drinking and doing everything in her power to keep Belle’s friends at bay. So obsessive was Dickie’s jealousy that she once drugged one of Belle’s favorite female employees because she thought Belle was paying too much attention to her (it wasn’t fatal, but the employee ended up losing her job). When Belle discovered that Dickie was having a secret affair with an underage female employee, she ended the relationship, but in typical Baruch benevolence she left Dickie some money to help her rebuild her life. Miller has managed to capture the spirit of the times in her descriptions of prewar and postwar Europe and America. As a biographer who’s sympathetic to her subject, she manages to reveal Belle’s many sides—her generosity, her intelligence, her openness to change—without painting her as a saint or heroine. The skepticism I felt when beginning the book—the introductory writing feels a bit Reader’s Digest-like—quickly vanished when Miller plunged into a deeper analysis of this fascinating life. Thom Nickels is the author of Out in History (2005).

____________________________________________________________________