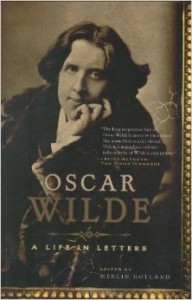

Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters

Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters

Edited by Merlin Holland

Carroll & Graf. 384 pages, $27.95

ONE HUNDRED YEARS after the death of Oscar Wilde in 1900, all of his known surviving letters—1,562 of them—were published, edited by his grandson, Merlin Holland (with the late Rupert Hart-Davis). Now Holland has edited a selection of those letters, shorn of scholarly impedimenta, to reach a broader public. In his words: “All of these editions … relied heavily on the scholarly apparatus of copious footnotes to put the letters in context and I feel that the time has now come to make my grandfather’s correspondence accessible to a broader public with only a minimum of editorial intervention. To this end, I have made a very personal selection of the letters, some 400 in total, which seem to me to reflect the man, warts and all.”

There are advantages and disadvantages to such an approach. On the one hand, Holland’s pruned-down volume is much more readable without the hundreds of letters that deal with tediously mundane matters. On the other hand, some of the letters really would benefit from footnotes.

Oscar Wilde left neither a diary nor memoirs, and no one close to him attempted to write a biography. Consequently, Holland opines: “His letters, particularly those written to intimate friends without thought of publication, are in effect the autobiography that he never wrote, and as close as we shall come to the magic of hearing that legendary talker in person.”

This may be true, but we cannot assume that Wilde’s most representative or important letters have survived. For example, Wilde was a great admirer of John Addington Symonds (author of the great pioneering polemic, A Problem in Greek Ethics) and corresponded with him for years, but none of his letters to Symonds is in The Complete Letters. In the aftermath of the trial, many of his acquaintances hastened to destroy any evidence that they had ever known him. Notwithstanding this caveat, I did enjoy once again reliving the Oscar Wilde saga, or Passion Play, and noticed many things that I had previously skimmed over.

The first letter, dated September 1868 and written when Oscar was not yet fourteen years old, is to his mother, Lady Jane Wilde, a brilliant and boldly unconventional woman—an Irish revolutionist in her youth, a poet, a linguist who did translations from half a dozen languages. She and Wilde’s father, Sir William Wilde, were among the foremost folklorists of the 19th century. Wilde’s letter to her, in a breezy and almost campy style, touches on a hamper of food he received, a regatta race he saw, clothing he needs, and so on. It is accompanied by a droll drawing of some officers in a nearby regiment. His next letter (June 1875), to Sir William Wilde, is written from Florence, where he was on holiday from Oxford. At the age of twenty he’s already a know-ledgeable æsthete. Descriptions of various buildings and art objects are illustrated with his own quite competent sketches. The next two letters, written to his mother from Milan a week later, are charming and informative. Already Wilde is a prose stylist of the first rank.

The next set of letters, written to fellow undergraduates Reginald (“Kitten”) Harding and William (“Bouncer”) Ward, is campy to the point of silliness, and the reader senses an underlying gayness, but some of the terms and allusions require explication. Keys to the coded language were provided by a work that transformed Wildean biography: The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2005), by Neil McKenna, an openly gay man. Thanks to McKenna, it is apparent that Wilde, Ward, and Harding are all gay, and consciously so. For example, Wilde’s letter to Ward (March 1877) contains the sentence: “My greatest chum, except of course the Kitten, is Gussy who is charming though not educated well: however he is ‘psychological’ and we have long chats and walks” [Wilde’s emphasis]. McKenna explains the covert meaning of psychological:

A new word, brought over from Europe on the wind of intellectual change, entered Oscar’s vocabulary halfway through his time in Oxford. ‘Psychological’ came to mean men who loved men, and reflected the wave of new thinking in Germany, Austria, and France that love and sex between men was a disturbance, a disease of the mind to be treated by the physician, rather than a crime to be punished by the courts. In Britain, the word became a kind of shorthand to refer to anything pertaining to love and sex between men.

Unfortunately, Holland chose to omit Wilde’s letter of 6 August 1876 to William Ward, which tellingly uses the word psychological:

I want to ask your opinion on this psychological question. In our friend Todd’s ethical barometer, at what height is his moral quicksilver? Last night I strolled into the theatre about ten o’clock and to my surprise saw Todd and young Ward the quire boy in a private box together. Todd very much in the background. He saw me so I went round to speak to him for a few minutes. He told me that he and Foster Harter had been fishing in Donegal and that he was going to fish South now. I wonder what young Ward is doing with him. Myself I believe Todd is extremely moral and only mentally spoons the boy, but I think he is foolish to go about with one, if he is bringing this boy about with him.

For most of 1882 Wilde toured America, lecturing on the æsthetic movement, and it was a grand success. College men had fun with him. Miners in Colorado were so smitten that they had him open a new vein, or lode, with a drill, and then presented him with the silver drill and named the new lode “The Oscar.” He and Walt Whitman were at least on kissing terms, and continued to correspond.

The saga continues: friendships; courtship and marriage; children; his great love and nemesis, Lord Alfred (“Bosie”) Douglas; the first plays; The Portrait of Dorian Gray; fame and fortune; the feud with Bosie’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry; the trials; imprisonment; the aftermath. Out of all this, a few letters stand out.

After his release from prison, reunited with Bosie, Wilde writes from Naples to his faithful friend, Robbie Ross (21 September 1897):

When people speak against me for going back to Bosie, tell them that he offered me love, and that in my loneliness and disgrace I, after three months’ struggle against a hideous Philistine world, turned naturally to him. Of course I shall often be unhappy, but still I love him: the mere fact that he wrecked my life makes me love him. ‘Je t’aime parce que tu m’as perdu’ is the phrase that ends one of the stories in Le Puits de Sainte Claire—Anatole France’s book—and it is a terrible symbolic truth.

Writing to Ross from Paris (18 February 1898), he wrote: “It is very unfair of people being horrid to me about Bosie and Naples. A patriot put in prison for loving his country loves his country, and a poet in prison for loving boys loves boys. To have altered my life would have been to have admitted that Uranian love is ignoble. I hold it to be noble—more noble than other forms.” A Life in Letters has no footnote on the word “Uranian”—but the Complete Letters does, giving its meaning as “homosexual” and citing its earlier use (in German) by Karl Heinrich Ulrichs and (in French) by André Raffalovich. Actually, as early as 1818, Percy Bysshe Shelley used “Uranian” to signify male-to-male eroticism in his translation of Plato’s Symposium and elsewhere.

A passage from Wilde’s letter to George Ives (21 March 1898) is often quoted: “Yes: I have no doubt we shall win, but the road is long, and red with monstrous martyrdoms. Nothing but the repeal of the Criminal Law Amendment Act would do any good. That is the essential. It is not so much public opinion as public officials that need educations.” Holland gives no note for this letter, having noted earlier that “Ives was a poet, penologist and low-key homosexual.” What he doesn’t mention is that (according to McKenna) Ives had sex at least once with both Oscar Wilde and Bosie. In 1893 Ives founded a secret society, The Order of Chaeronea, to advance the “Cause”—a forerunner of the Mattachine Society. Wilde and Douglas were almost certainly members. When Wilde wrote “we shall win,” this is what he had in mind.

John Lauritsen’s most recent book is The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein (2007). He maintains a website at paganpressbooks.com/jpl.