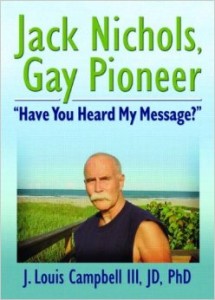

Jack Nichols, Gay Pioneer: “Have You Heard My Message?”

Jack Nichols, Gay Pioneer: “Have You Heard My Message?”

by J. Louis Campbell III, JD, PhD

Harrington Park Press

358 pages, $69.95 (paper: $29.95)

THE 1970’s was the golden age of gay bar guides, those little publications with pictures, personal ads, and, week after week, articles by local activists and commentators. Those articles, now mostly lost, helped form GLBT communities in towns all over America. Jack Nichols wrote hundreds of such pieces. The bibliography of his newspaper and magazine articles runs to 35 pages in J. Louis Campbell’s study of his life and work. But this is not the main reason we should know about this man. Jack Nichols was present at the creation.

A famous photograph, reproduced in this book, shows the thirteen people who picketed the White House on May 29, 1965, in the second demonstration sponsored by the Washington, D.C., Mattachine Society. The women in the photograph wear dresses or skirts, the men suits and ties. Jack Nichols, tall and clean-cut, is in the center of the picture carrying a sign. We see his face and those of several other demonstrators, who look straight ahead with serious, determined expressions. It’s easy to imagine that they knew they were making history. To Nichols’ right is an armed policeman, arms akimbo, his back to the camera as if to deny the changes that were coming.

The man in the center of the picture was born in 1938 into mostly fortunate circumstances. The one exception was his father, who was a professional baseball player before becoming an FBI agent. Since Nichols knew from an early age that he was gay—he came out to his mother at age twelve—he was bound to clash with such a man. They parted for good when the 1965 demonstration brought Nichols to the attention of J. Edgar Hoover, and his father, fearful that this could jeopardize his own career, threatened his son’s life. Nichols’ parents had divorced when his father returned from World War II. His mother Mary, who outlived her son by four months, was an Auntie Mame figure in her grit and style and the perfect parent for a precocious boy who would choose his own religion (Baha’i), his own friends (including the family of an Iranian diplomat), and his own high school curriculum (which included study of Farsi and Walt Whitman). Nichols and his mother lived with her Scottish parents in a comfortable house in Chevy Chase. His grandfather, Murdo Finlayson, a successful builder, nightly declaimed the poems of Robert Burns at the dinner table. His grandmother Euphemia allowed him to neck with his male dates in the driveway.

Campbell’s book is strongest in the early chapters, where he describes how the colorful characters of Nichols’s childhood combined with his own courageous and independent personality to free him from the pervasive homophobia of the 1950’s. By the time he was nineteen, Nichols and his first boyfriend had purchased a house and lived openly as a couple. Nichols’ formal education ended with high school, but he created his own college experience via bookstores and libraries and debates with friends. In 1960, he met Frank Kameny when he overheard him talking about Donald Webster Cory’s The Homosexual in America at a party. Within a year, these two giants of the gay rights movement had founded the Washington, D.C., Mattachine Society.

Rejecting the prevailing conservatism of “homophile” organizations of the era, the members of D.C. Mattachine were determined to effect social change. One path led them to the picket line, where they protested the treatment of gays by the government and the military; another led to the psychiatrist’s office. At the time, one of the few acceptable places to discuss homosexuality was with a psychiatrist, and the diagnosis was dismal: homosexuals were told they were sick and needing a cure. Nichols and Kameny refused to accept the sickness model. They knew the struggle for civil rights could not begin until gay people cast off self-hatred and replaced it with self-esteem. Nichols analyzed the research of leading psychiatrists, attacked their methods and conclusions, and beat them at their own game.

It would be impossible to overestimate the debt we owe these early activists, Nichols foremost among them, who said “no” to the pervasive homophobia of church, state, and the medical profession. By the 1970’s, Nichols had moved from activism to writing about gender construction and male liberation. Campbell attempts to weave the story of Nichols’ personal relationships into that of his intellectual development. The result is not as satisfying as the first half of the book. Nichols himself gets lost in the large amount of background material summarized in the text.

Most of Nichols’ books are no longer in print and his ideas on topics like androgyny and anarchism were not groundbreaking. What is of enduring interest about Jack Nichols, in addition to his pioneering work as an activist, is the man himself. We never really come to know this handsome, self-educated, modest, cheerful man who, along with his lover Lige Clark, became “the most famous homosexuals in America” when they began writing a gay column for Screw magazine. Even then, Nichols had to work as a motel night clerk to support himself. He went on to fall in love with two men who came to tragic ends, and knew most of the men and women responsible for the modern GLBT rights movement. He lived 21 years with a rare, incurable form of cancer until his death in 2005.

Campbell’s writing leaves much to be desired. The book has the dogged quality of a dissertation, with its relentless citations, tangential discussions, and statements of the obvious. Good editing would have helped. Surely it would have prevented the author from ending every chapter except the last with the words “as we learn in the next chapter.” Still, it is wonderful to have a permanent record of the life and accomplishments of Jack Nichols. That we want to know more about this man indicates that Campbell has succeeded in conveying a sense of his significance.

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the Univ. of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he also teaches courses on literature and medicine.