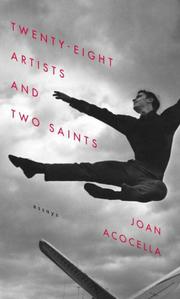

Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints

Twenty-Eight Artists and Two Saints

by Joan Acocella

Pantheon Books. 544 pages, $30.

JOAN ACOCELLA writes beautifully on every topic she covers, and this collection of her biographical essays over the last two decades shimmers with droll observations, vivid images, and wise insights about important artists. Her real subject is 20th-century modernism, and she examines some of the important people who created it. Purposely, it seems, rather than focusing on the great icons of the movement, she spotlights figures who have been neglected or whose discipline has been appreciated only by a cultural elite.

Modern dance ranks foremost among the major under-analyzed disciplines. Acocella’s essays on Nijinsky, Frederick Ashton, Lincoln Kirstein, Jerome Robbins, Suzanne Farrell, Baryshnikov, Martha Graham, Bob Fosse, and Twyla Tharp tell the story of how Diaghilev reinvented Russian ballet in Paris early in the 20th century, and how it erupted onto the American cultural scene largely through the agency of Lincoln Kirstein, who brought choreographer George Balanchine to America to found the New York City Ballet. Balanchine dominates all of these essays; curiously, Acocella never accords him one of his own. Although the great modern dance troupes often toured nationally, their incandescence blazed mostly in New York. Acocella celebrates the modern choreographers’ achievements and correctly stresses their impact on the more popular arts. Simply stated, Balanchine and his successors transformed how artists saw movement, how writers described the relations between people and space, how filmmakers choreographed their works, what music was valued, and ultimately how people moved. Rock ’n’ roll music constituted the only rival influence, and Balanchine’s successors—especially Twyla Tharp—made good use of that, too. Acocella points out that dance, the most evanescent of the great arts, can’t be preserved for long after a troupe breaks up or the lead dancer retires, and she scrupulously attempts to preserve what’s possible in words.

Acocella also focuses on neglected or undervalued 20th-century writers. These include a number of Europeans: Italo Svevo, Stefan Zweig, Primo Levi, Joseph Roth, Sybille Bedford, Penelope Fitzgerald. She achieves special poignancy in her observations on how the Middle Europeans labored to write under the Kafkaesque weight of mid-20th-century history. She directs us to very important and idiosyncratic authors that we may have heard of but never read. For good measure, she includes essays on some more famous figures: H. L. Mencken, Dorothy Parker, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Yourcenar, Saul Bellow, Frank O’Hara, Susan Sontag, and Philip Roth. These essays, while they may bring little news to regular readers, add a fresh twist to the subject and invite us to revisit them. (I have been struck a lot recently by how differently a book—even a quip—reads in your fifties than it did in your twenties.)

As Acocella points out in her introduction, an extraordinary number of the artists she treats were gays and Jews, or moved in circles that included a lot of gays and Jews. The centrality of homoeroticism to much artistic production has been no secret since Plato, and Acocella gives this topic its due. She concentrates not so much on who slept with whom as on how erotic attraction fuels creativity, from Diaghilev’s affair with Nijinsky to the fact that Frank O’Hara wrote most of his poems during the two short periods when he loved another man. It was Susan Sontag who pointed out in “Notes on Camp” (in Against Interpretation, 1966) that the key sensibility of the late 20th century would be created by a dialectic between Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual æsthetics. (She might have added Jewish comedy, which itself, from Mel Brooks to Jon Stewart, has been a product of moral seriousness.) If we can’t laugh sometimes in the face of disaster, we will die; gays and Jews have often taught us best how to do that. Acocella’s book bears out Sontag’s premise.

In her introduction, Acocella defends herself against the charge that this collection is a grab-bag by saying that these are her essays that she liked best. As a critic for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, she was able to write on a wide range of artistic topics, always returning to dance as if to her true love. This raises the question of whether she might have made two books of this material: one on the history of modern American dance and another on important but neglected modernist writers. Many of the biographies that involve the same topic—such as Balanchine’s pervasive influence on modern American dance—create repetition. Alternatively, she might have grouped these essays into two sections with an introduction that provided an overview of each. Her inclusion of two saints—Mary Magdalene and Joan of Arc—reveals that she’s a bit out of her element when addressing early Christianity or 15th-century French history. But if it’s a grab-bag, what it brings together is well worth reading, among other things a lot of evidence for the central influence of gay people and sensibilities on a century of American culture.