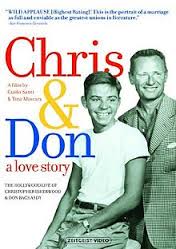

Chris & Don: A Love Story

Chris & Don: A Love Story

Directed by Guido Santi and Tina Mascara

Seitgeist Films

IT HAPPENED on a typical day in sun-drenched Southern California in the early 1950’s. Two men met on the “queer” side of Will Rogers Beach in Santa Monica. It was, despite the setup, all rather innocent. Within two months, they would begin a fearless, challenging, and devoted romance that would last for the next 33 years. On that afternoon, in that moment, all could have been lost to history save for the fact that one of the men was 49-year-old Christopher Isherwood, already an accomplished author, and the other a captivating and spirited eighteen-year old, Don Bachardy, whose portraits of the celebrated and powerful would one day enchant the world.

Over a decade ago, Jim Berg and I began studying the Anglo-American writer Isherwood. It became immediately clear to us that to do justice to the American Isherwood, we would have to focus on both Isherwood and his longtime partner, Don Bachardy. In the introduction to our first book, The Isherwood Century, we included a section called “Chris and Don Alive,” in which we wrote that we hoped to provide readers with a “sense of Isherwood and Bachardy actively constructing their lives and work together.” There’s another part in the book called “Artist and Companion” that’s dedicated to both men and their collaborations. To introduce that aspect of the story, we wrote: “With few models to emulate, Isherwood and Bachardy developed their relationship as lovers, partners, friends, and collaborators. In spite of the notoriously homophobic environment in the Hollywood of the 1950’s, they insisted on defying the prevailing culture and lived their lives in the open.”

Jim and I are both thrilled to be included in the new documentary, Chris & Don: A Love Story, directed by Guido Santi and Tina Mascara.