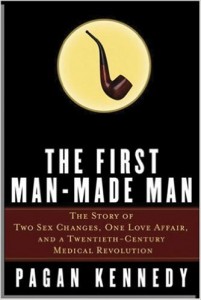

The First Man-Made Man

The First Man-Made Man

by Pagan Kennedy

Bloomsbury. 214 pages, $23.95

CHANCES ARE that, as soon as you were old enough to form a cognizant thought, some adult was asking you what you wanted to be when you grew up. Did you want to be a cowboy, a nurse, or a fireman? Perhaps you longed to be a police officer, a farmer, or a rock star. Maybe it was in your future to be a truck driver, a veterinarian, or a teacher. Laura Dillon wanted to be man when she grew up. Laura always felt that she was born in the wrong body, and in The First Man-Made Man, by Pagan Kennedy, we learn that Laura got what she wanted—and a whole lot more.

Born in England in 1915 and abandoned by her parents some ten days later, Laura Dillon always felt embarrassed by the dresses and dolls that her elderly aunt-guardians forced her to wear. She wanted desperately to be a boy despite the girlish future her aunts envisioned, and she craved belonging to a male society that she had mythologized for herself. As a little girl, she did very unladylike things (for the mid-1920’s), like building furniture and dreaming of safari adventures.

For Laura Dillon, puberty wasn’t kind. She hated her blossoming female body. Even more, she hated the fact that boys saw her as a woman. Dillon went to college, joined a rowing team, and flirted with passing into a society of men. On the cusp of adulthood and able to get male hormones from a pharmacy, Dillon began her transformation. She dressed in men’s clothing as her shoulders squared and her voice deepened. She grew a goatee, took up smoking a pipe, and started penning thoughts on gender and identity. As World War II overtook Great Britain, Laura Dillon became Michael Dillon.

In the early to mid-1950’s, Great Britain had a “mayhem law” that forbade removal of male anatomy from any potential soldier. America had no such laws, but the subject was rarely broached by doctors. Gender reassignment surgery was a definite anomaly in medical circles on both sides of the Atlantic. Still, Michael Dillon persisted, finally locating a sympathetic doctor who was willing to give him the surgery he craved. The surgery was successful as far as Dillon was concerned—by all accounts, he was proud of it—but he was offered no psychological support, something that no one deemed unnecessary at the time. Michael Dillon was on his own.

Part history, part biography, and part medical story, The First Man-Made Man is an intriguing book about a person who was ahead of the times in many ways and a society that wasn’t ready to address this new idea. This is also a sad book, because in the end Michael Dillon is a lost soul, forever searching for a place where he could be himself, always on the periphery and never quite belonging. This is not to say that Kennedy succumbs to the maudlin; her writing is lively but admirably factual and objective.

The other side of this fascinating book is Kennedy’s two-pronged timeline of plastic surgery and gender study. Because of terrible injuries in the two World Wars, several forward-thinking doctors saw a need for reconstructive surgery, which spawned an industry that not only became vital to war victims but also to people who weren’t satisfied with their bodies, including those who longed for gender reassignment.

______________________________________________________

Terri Schlichenmeyer is a syndicated columnist based in Wisconsin.