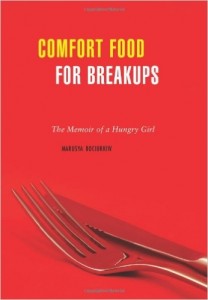

Comfort Food for Breakups: The Memoir of a Hungry Girl

Comfort Food for Breakups: The Memoir of a Hungry Girl

by Marusya Bociurkiw

Arsenal Pulp Press. 171 pages, $16.95

MARUSYA BOCIURKIW is a first-generation Ukrainian-Canadian who’s a professor, a novelist, a poet, a performance artist, and an avid blogger (her entertaining and well-illustrated site is at marusya.lazarapress.ca). In this memoir, which is also a cookbook, she covers some well-traveled territory in lesbian literature—a mildly dysfunctional family that was “full of ghosts,” the struggle of coming out, lesbian love affairs gone wrong, progressive politics—yet her lovely prose style elevates the mundane. Her large family includes a street-musician brother who died young and a father whose life in Canada was haunted by his experiences in a forced labor camp during World War II.

Although she thanks her mother effusively in her acknowledgments, the two women were apparently estranged for many years and at some points could connect only around food. Luckily, there was a great deal of good food throughout her life, though food “was never an uncomplicated thing in my family.” In a chapter called “Torte,” about her brother’s death, the author writes: “For all of our bitterly argued differences, we [she and her mother]have one big thing in common: an abiding fascination with the ways and meanings of the culinary arts. Food creates a kind of dialogue between us, an implicit assent missing in other aspects of each other’s lives.” The chapter ends with a two-page recipe for torte, and the mere act of reading it is exhausting. Marusya Bociurkiw’s you-are-there descriptions of her domestic and European travels (“sipping Campari in a gay bar in downtown Turin”) sometimes slip into a second-person-singular immediacy, especially in her descriptions of bus travel in Turkey where “you’ll share the dried Turkish apricots and Swiss chocolate that you always carry with you.” Raised in Edmonton, Alberta, and shuttling all over Canada, she lived in Montreal for three years, where the east side was “always packed with unemployed bon vivants—myself and a stylish, insolent gang of lesbians among them. … It seemed at the time that our blood families had abandoned us. Perhaps the truth was that we had abandoned them, so that we could expand so queerly into the world.” While Bociurkiw does not appear to be a vegetarian, most of the recipes—sometimes standing alone to close a chapter, sometimes folded in as a paragraph of prose—are for pasta, vegetable side-dishes, and desserts. Throughout the memoir she describes food in great detail, whether prepared at a restaurant, at home, or at a lover’s home (where they “measured time in [their]relationship by its gustatorial highlights,” lovingly and delicately). “The pages of my cookbooks are a palimpsest, layered with notes and food stains, and the complex flavors of love and loss,” she writes. We can all appreciate sentiments such as this, whether we own such a cookbook and never use it, or use it daily, or dispense with cookbooks altogether.