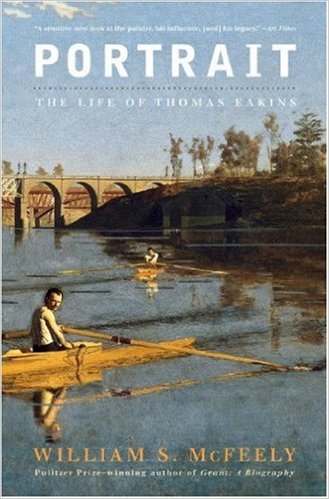

A painter and photographer who’s acclaimed by some critics as the best portrait artist in American history, Thomas Eakins is today a very hot property. His 1875 painting The Gross Clinic, which depicts Dr. Samuel Gross performing surgery, is still in the news. Purchased by Thomas Jefferson University in 1878 for $200, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has recently fended off a bid for the painting rumored to be $68 million. Once considered too gory for general display, illustrating as it does Eakins’ thorough understanding of anatomy, it is now considered by some to be the greatest 19th-century American painting.

Eakins was born into comfortable circumstances in Philadelphia in 1844. His father, with whom he was very close, nurtured his son’s artistic abilities. His mother was probably manic-depressive, and Eakins’ own depression increased as he grew older. Civil War historian William McFeely, who won a Pulitzer for his biography of Ulysses S. Grant in 1981, has written, if not a hagiography, a very sympathetic and gay-affirming book about Eakins’ life and work. Portrait proceeds in chronologic order with an emphasis on Eakins’ youth, notably his rigorous art studies in France and Spain for four years beginning in 1866. In quoting from Eakins’ letters home during his Wanderjahrs, one finds the casual racism and anti-Semitism that were all too common at that time. To his credit, however, Eakins did believe in equality for women, and as a student he was friendly with the apparently lesbian Rosa Bonheur.

Despite the fact that Eakins’ name appears in most compendia of gay artists and other notables, his bisexuality or homosexuality is far from established. But McFeely treats it as the overarching theme of Eakins’ life. “There were many dimensions to Eakins’ life that seem incompatible with conventional masculinity,” he observes, ranging from his choice of friends to an early failed romance with a woman. The veiled letters of his childhood friend and near-fianc ée, artist Emily Sartain, certainly raise many questions. Sidney D. Kirkpatrick, in his exhaustive but highly readable The Revenge of Thomas Eakins (2006), states flatly that “Eakins’ many scandals all involved women. A cavalcade of nude men modeled for him.” He dismisses the notion that his close friendship with Walt Whitman provides evidence for homosexual proclivities. Eakins’ The Swimming Hole (1883), which features naked youths on a raft and was inspired by Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” can certainly be viewed as homoerotic; and it’s true that Eakins took many nude photographs in preparation for the painting. But a year after painting The Swimming Hole, he married artist Susan Macdowell, formerly his student. Their marriage appears to have been very happy, albeit childless, enduring until Eakins’ death in 1916. On the other hand, McFeely puts forth the thesis that Eakins had a long-term love affair with another former student, Samuel Murray, who was later a well-known sculptor and became Eakins’ devoted nurse in his last days. It was Murray who had introduced Eakins to Whitman.

In Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist (2005), author Henry Adams offers a scholarly look into Eakins’ life and work, offering some close readings of his art that are fascinating. For instance, in discussing Eakins’ portrait of his niece Ella, called Baby at Play (1876), Adams makes much of the fact that the little girl—who has a short haircut, and whose parents are known to have wanted a boy—has forsaken her rag doll for building blocks. Adams wonders if this presages an incident two decades later after which veiled, vague accusations of sexual molestation hovered over Eakins. Ella, who as a young woman was confined to a psychiatric hospital, died by her own hand in her early twenties. McFeely believes there’s no doubt that she was mentally ill; other critics have many doubts, some suggesting that she may have been a lesbian.

Eakins was famously ousted from his teaching position at the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts, in 1886, in part because he removed a male model’s loincloth in a mixed-gender life studies class. He was also known for “intense relationships” with his students, both in and out of the classroom, and for the many nude photos he took of himself and his students, both male and female. McFeely states: “His flamboyant exercise of freedom, of even exultation, was capable of yielding to a dark streak of depression.” He quotes art critic Sylvan Schendler (in Thomas Eakins, 1967), who called the removal of the loincloth “an immolation.”

McFeely had access to a large archive known as the Bregler Papers, which became available in the late 1980’s. Charles Bregler was a devoted student of Eakins, who kept detailed diaries of his student years and became the keeper of the Eakins flame. McFeely’s biography, well-researched, well-written, and beautifully illustrated with both black-and-white reproductions and color plates, certainly adds to our knowledge of Eakins. But as the Bregler Papers continue to be mined, there are sure to be more biographies, and more theories about his sexual orientation, to come.