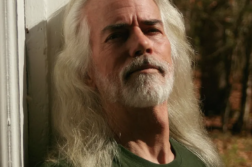

Terrence McNally doesn’t consider himself an activist playwright, but he does believe that in the scheme of things “All theatre is political.” The winner of four Tony Awards, McNally, at 67, is still a man of the theater in his time, on the active duty list of out gay American dramatists. At last season’s Tony Awards, actor David Hyde Pierce quoted the playwright’s credo: “If a play isn’t worth dying for, it isn’t worth writing.”

McNally’s theatrical range has the tenacity and breadth to invoke everything from the legendary specter of Maria Callas (Master Class) or Hindu spiritualism (A Perfect Ganesh) or even ignite a passionate straight middle-aged affair (Frankie and Johnnie at the Clair de Lune). In Corpus Christi, he turned Jesus into a gay Messiah and, lest we forget, he perpetrated a mob farce in a gay bathhouse in The Ritz. Nothing seems out of his league. “People still want to be a little surprised in the theatre,” he says with a sinister smile.

McNally himself has often been surprised by the popularity of his plays. Of his long-running Broadway hit he commented: “When I wrote Master Class people said the only people who will like this play are opera fanatics and Callas fans and there aren’t that many of them anymore. So I thought, “well that’s the play I want to write.” McNally many hits also include Love! Valor! Compassion!, The Lisbon Traviata, and Lips Together, Teeth Apart. And he has transformed thorny book-to-a-musical hits like The Full Monty, Kiss of the Spider Woman, Ragtime, and A Dancer’s Life (currently on tour with Chita Rivera).

Some Men, one of his recent plays, begins with a gay wedding and time-travels through eighty years of hidden and not so hidden queer history. It seems more than a coincidence that it opened in 2006 (at Second Stages in New York) just as the national debate on same-sex unions w as again heating up. It’s just one of several McNally works in various stages of development, including Deuce which will also open in Manhattan next spring.

as again heating up. It’s just one of several McNally works in various stages of development, including Deuce which will also open in Manhattan next spring.

McNally’s has had his theatre scandales, one famously backstage bitchy one involving Nathan Lane, who bowed out of the movie version of L!V!C!, choosing not to reprise his star turn as Buzz in the Broadway show. But the feud is now officially over: Lane was in the Terrence McNally-Scott Wittman-Marc Shaiman musical Catch Me If You Can last August and is co-starring in Deuce. McNally had a brush with controversy over his 1998 play Corpus Christi, an elegiac retelling of the gospel that cast Jesus and his disciples as gay men. He says the idea seemed perfectly natural to him that Jesus could be homosexual and a completely valid concept for commercial stage. The drama not only drew protests but bomb threats in the New York production, causing some performance cancellations.

Among his many passions, the one he has for divas of all kinds loom large in Some Men, which was commissioned two years ago by Sundance Theater Institute Laboratory. The sketchy theme turned into fifteen-scene montage of gay history that begins at a same-sex wedding and flashes back to depictions of the Harlem Renaissance gay café scene in 1925, then moves through Stonewall, the disco and bathhouse culture of the 70’s, AIDS, and to some New York gay seniors reminiscing about the halcyon days of their (albeit closeted) youth.

During the opening week of Some Men at The Philadelphia Theater Company (PTC) last summer, McNally discussed topics gay, political, personal, and sexual—and even had a few comments about the Pope and Judy Garland. Here is some of what he had to say.

Lewis Whittington: Did you write this play to weigh in on the gay marriage debate?

Terrence McNally: The idea was to write a play about the unique connection between gay men and divas, which quickly became a play about gay men and marriage.

LW: You touched on your method and the Zen of writing during the performance Q & A. Can you elaborate?

TM: I’m not very schematic. You try to write about things in a way you haven’t heard before. You have to put emotion in a scene that has a conclusion. Dialogue comes very easy if you know what the characters are doing. Students of play writing mistake dialogue for a scene.

LW: Are you making a lot of changes in Some Men before you get to New York [in November]?

TM: This play is still finding its expression. That’s what makes this process so different from other art forms. I wrote my first play was when I was 23. I never wrote a novel or a short story. I don’t feel like a writer, I feel like a playwright; and a playwright knows whether an audience is engaged or not. We’re present and we know if our work is succeeding or not. At intermission you’re in the bathroom and you’re at the urinal and invariably someone turns to you and says “Boy this is good” or “I wish I was someplace else.” During a matinee performance of Some Men, a man bolted out of his seat in the middle of an anonymous post-disco tryst where the two actors are nude and move so close to each other that their penises are touching. Ushers heard him ranting in the lobby about the actors being naked with their cocks are touching. They are actors and they are not going to get a hard-on. Nudity is very different from sexual activity. Before Stonewall we defined ourselves through sex, so I show that.

LW: Did you deliberately want to address same-sex marriage in this play because it’s such a timely issue?

TM: Look at the Pope denouncing gay marriage because it will undermine traditional marriage. What he means is that the church hates homosexuals, why don’t they just say that? Don’t say, “We love homosexuals but are against gay marriage.”

LW: How much do you stress over the creative process?

TM: Know what the characters are doing is my only rule of thumb. I feel blessed when I turn on the computer and something usually happens. I think technique comes into play when you do rewrites. I’ve been working on technique on this play for the past two weeks. Rewriting separates the men from the boys. We also have actors, directors, and designers interpreting us. In a way, we’re interpreted the way musicians interpret a composer. But when you have actors like John Glover, Nathan Lane or Zoe Caldwell doing your stuff, it’s thrilling for my words to be interpreted by these artists.

LW: Corpus Christi seemed to get lost to its controversy in the beginning even though the play outlived the scandal and has since had many productions without incident. How did you feel about that?

TM: People went expecting a dirty show, and it’s not that. Imagining the story of Christ and the apostles as if they were gay men and, other than that, it’s quite traditional. Why should I be told by the church that I have no right to participate in this story? I was consciously emulating a morality play. It’s a ritual more than a play. You know, after all, how it’s going to end. The notion that Christ could be a gay man made people go crazy. The play got lost because of homophobia—because it exposed the homophobia in our society.

[TM’s husband Tom entered the room at this point, turning the discussion to more personal matters. A lifelong runner—and smoker— TM stays off the track because he lost a lung to cancer over five years ago.]

LW: You were married to your partner Tom Kirdahy [a lawyer specializing in sexual minority civil rights cases]in Vermont back in 2004. You’ve been very passionate on the issue of same-sex marriage.

TM: When it first started I didn’t feel so passionate about gay marriage, but now I see that it is the final fight. My relationship with Tom is as good as my mother and father’s, and I’m no longer willing to accept that it is anything less.

When I first met Tom I told him on the third date that I had lung cancer.

LW: You are cancer-free now?

TM: Yes. I can’t run very far any more, but Tom and I had a very physically arduous trip to India earlier this year and I was fine. We have an intimacy that I’ve never had in my life. He inspires me too. Tom is a lawyer who works with people with hiv/aids—a public-interest lawyer who represents the poor and sexual minorities. He actually got the Teamsters to compensate a lesbian couple.

LW: Where would you say we are now in the struggle for gay civil rights?

TM: The whole gay civil rights issue goes back to this: Just be out, just be strident. You don’t have to be in politics or write plays; just be out. That is how social change happens.

Lewis Whittington is an art writer who frequently contributes to Philadelphia Weekly and to Dance magazine.