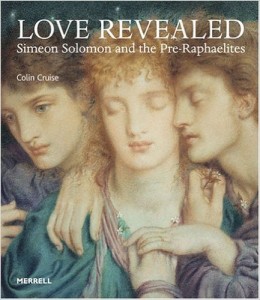

Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites

Love Revealed: Simeon Solomon and the Pre-Raphaelites

Traveling exhibit, 2006

Catalog by curator Colin Cruise

Merrill. 192 pages, $49.95

SIMEON SOLOMON, a gay, Jewish Pre-Raphaelite painter of the 19th century, has figured prominently in most studies of gay male painting, and there has been an upsurge in scholarly interest of late. However, it is still fair to say that his life story eclipses his artistic achievement. No wonder: in 1874, Solomon was among the first victims of a spate of high-profile prosecutions of gay men in London, convicted of “gross indecency.” Hence James Smalls, in Homosexuality in Art (2003), in comparing Solomon with Thomas Eakins and his English follower Henry Scott Tuke, writes: “The label ‘homosexual’ can be more assuredly applied to the most ‘out’ of 19th-century artists, Simeon Solomon.” For art historians interested in the representation of same-sex desire, Solomon’s transparency comes as welcome relief after the necessary circumspection concerning Eakins, Girodet, Flandrin—in fact, just about everyone after Caravaggio.