Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications

Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications

and Community, 1940’s-1970’s

by Martin Meeker

University of Chicago Press. 320 pages, $75 ($25.00 paper)

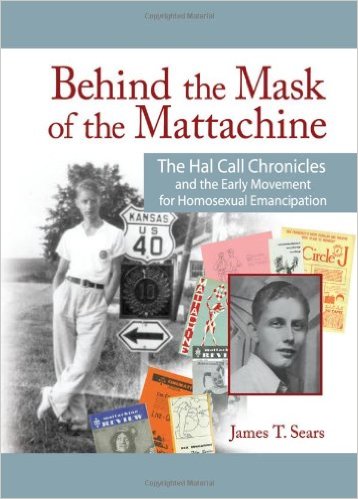

Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation

Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation

by James T. Sears

Haworth Press. 540 pages, $34.95

READERS of the Hobby Directory, a typewritten newsletter for “men and boys” published in the 1940’s, occasionally placed ads seeking correspondence with like-minded “Navy men” who shared their interests in physical culture, ballet, and sunbathing. Such requests, which appeared under the innocuous heading “Contacts Desired,” help Martin Meeker rethink the contacts that gay and lesbian Americans desired between the late 1940’s and the early 1970’s. By placing “the politics of communication” at the center of his story, he offers an interpretation of postwar America more nuanced and textured than earlier accounts that focused solely on politics or sex. And yet, as James Sears’ biography of gay activist Hal Call shows, “contacts” are difficult to separate from “desires.”