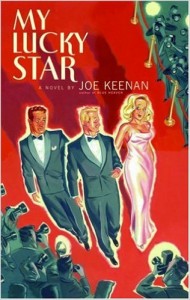

My Lucky Star

My Lucky Star

by Joe Keenan

Little, Brown & Co. 361 pages, $24.95

I REALLY WASN’T EXPECTING another novel from Joe Keenan. Several years ago, he’d written two perfect farces, Blue Heaven (1988) and Putting on the Ritz (1992), featuring narrator Philip Cavanaugh and his ex-lover Gilbert Selwyn, who would always draw Philip into impossible situations, eventually to be rescued by Philip’s writing partner Claire Simmons. In these books, Keenan demonstrated a control over intricate plotting, a mastery of the comic first-person narrative voice, and a gift for loopy similes that suggested that here at last we had found, in this struggling New York writer, a P. G. Wodehouse who was actually gay. Given the sturdiness of the basic set-up, there was every reason to assume that a Wodehousian stream of novels would continue to flow.