Published in: July-August 2006 issue.

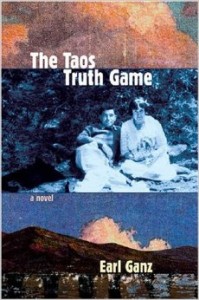

The Taos Truth Game

The Taos Truth Game

by Earl Ganz

University of New Mexico Press.

320 pages, $24.95

MYRON BRINIG, whose lifetime virtually spanned the 20th century, is all but forgotten today. His name is rarely found in compendia of gay writers, yet he was, according to the Gay & Lesbian Literary Heritage (1995), the first American Jewish novelist to write in any significant way about the gay experience. Upon arriving in the desert Southwest in 1933, already a popular novelist, he found himself among the day’s intelligentsia at the salon of the legendary Mabel Dodge Luhan.