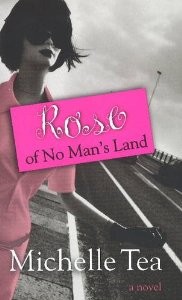

Rose of No Man’s Land

Rose of No Man’s Land

by Michelle Tea

MacAdam/Cage. 306 pages, $22.

“YES, ABSOLUTELY, this was the greatest day of my life,” declares Trisha Driscoll, the fourteen-year-old outer suburbanite narrator of Michelle Tea’s latest whirlwind street-girl adventure, Rose of No Man’s Land. During her nonstop killer of a day, Trisha starts and gets fired from her very first job, encounters a creepy, drug-dealing kiddie pornographer, smokes cigarettes and gets high for the first time, loses her virginity to another girl in the handicapped stall of a Chinese restaurant’s bathroom, goes diving for coins in that restaurant’s enormous fountain, and even buys herself a real, symbolic tattoo to mark the entire occasion. Like Holden Caulfield many years ago, Tea’s young lesbian protagonist comes of age in a single long, blissful, dangerous night. However, this coming-of-age story—also like Holden’s—could only belong to Trisha’s own generation.