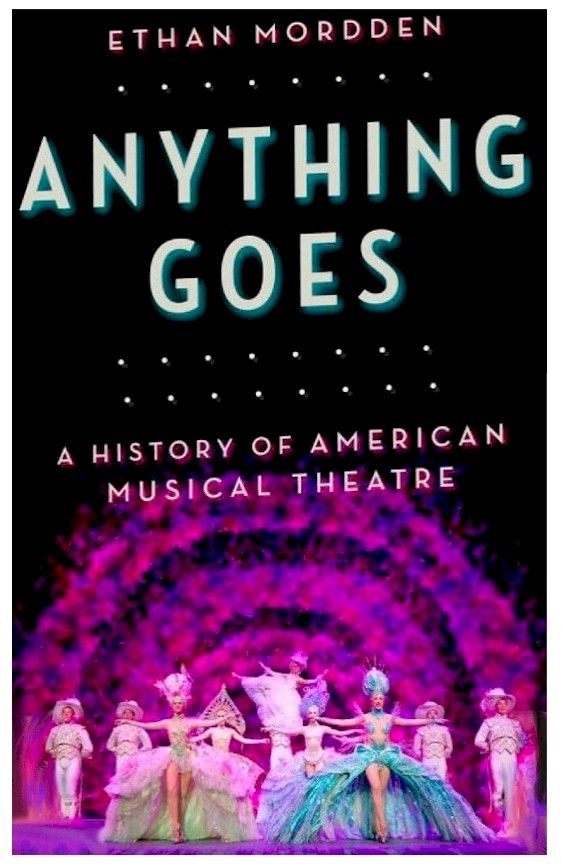

Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre

Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre

by Ethan Mordden

Oxford Univ. Press. 346 pages, $29.95

The Passionate Attention of an Interesting Man: A Novella and Four Stories

The Passionate Attention of an Interesting Man: A Novella and Four Stories

by Ethan Mordden

Magnus Books. 223 pages, $19.99

“I’M TELLING YOU, the only times I really feel the presence of God are when I’m having sex, and during a great Broadway musical,” a hyper-sexed Father Dan reveals to the title character Jeffrey in Paul Rudnick’s 1993 comedy about gay life at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Even as he brazenly attempts to seduce the emotionally confused stranger in the confessional, the strategically blasphemous priest warns him that Satan is real: “Phantom. Starlight Express. Miss Saigon! Know ye the signs of the devil: overmiking, smoke machines, trouble with Equity.”

Although novelist and theater historian Ethan Mordden invariably writes in a more judicious and measured style of argument, he shares with Rudnick’s flamboyant Father Dan a reverence for the life-affirming properties of American musical theater.

In that same essay, he reveals that from an early age he studied the theater pages of The New York Times and found his intellectual curiosity stimulated by an arresting logo or by a provocative title: “somehow I comprehended that the theatre was going to be my education.” Indeed, his obsession with musicals allowed him to escape the limits imposed on the imagination by family, church, and school, limits that his straight peers seemed to have had no difficulty accepting. “Musicals aren’t a fetish,” he concludes, “they are the stimulation of the cultivated.”

The extent to which musical theater has proven a lifelong stimulus for Mordden is on display in his new one-volume history of the musical stage. Mordden has been writing both informatively and entertainingly on this topic for nearly forty years, beginning with Better Foot Forward (1976), his initial attempt at a one-volume history, continuing through Broadway Babies: The People Who Made the American Musical (1995) and critical biographies of particular “Broadway babies” (namely Florenz Ziegfeld, Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, and Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II), and concluding with a magisterial seven-volume history that proceeds decade by decade from Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s (1997) to The Happiest Corpse I’ve Ever Seen: The Last Twenty-five Years of the Broadway Musical (2004). In the process he has established himself as the single most authoritative historian of American musical theater.

The extent to which musical theater has proven a lifelong stimulus for Mordden is on display in his new one-volume history of the musical stage. Mordden has been writing both informatively and entertainingly on this topic for nearly forty years, beginning with Better Foot Forward (1976), his initial attempt at a one-volume history, continuing through Broadway Babies: The People Who Made the American Musical (1995) and critical biographies of particular “Broadway babies” (namely Florenz Ziegfeld, Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya, and Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II), and concluding with a magisterial seven-volume history that proceeds decade by decade from Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s (1997) to The Happiest Corpse I’ve Ever Seen: The Last Twenty-five Years of the Broadway Musical (2004). In the process he has established himself as the single most authoritative historian of American musical theater.

His latest book, Anything Goes, far from being merely a rehash of his earlier works, offers the surest description to date of the roots and evolution of the musical, and represents Mordden’s own revised conclusions after almost forty years of considering these issues. Whereas Better Foot Forward opens with the sentence “It really begins with Show Boat [1927],” Anything Goes situates the start of musical theater with John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) and explores the kaleidoscopic ways in which a host of radically different forms of entertainment—the ballad opera, Gilbert and Sullivan’s Savoy Operas, Offenbach’s opéra bouffe, the American minstrel show, the burlesque revue, pantomime, Florenz Ziegfeld’s extravaganzas, and musical farce—morphed into musical comedy and operetta and eventually into the musical play. Mordden focuses upon the relationship between the score and the book from the early days—when lyrics offered only a slim pretext for the musical numbers and depended primarily upon the vocal style of the billed performers or the size of the singing and dancing choruses—to the moment when librettist-lyricists like Harry B. Smith and Oscar Hammerstein effected “a rapprochement between what the plot was doing and what the music was saying.”

Along the way, the author offers a valuable anatomy of song genres—for example, the establishing song, the wanting song, the moon song, the new dance sensation, or the comic novelty song—and descriptions of such long-forgotten hit plays as The Black Crook (1866), Evangeline (1874), El Capitan (1896), The Red Mill (1906), and Good News! (1927). Although he notes that Good News! “remained perhaps the single most popular show among high school dramatic clubs into the early 1960s,” this play, like the other titles mentioned, is rarely discussed today. Nevertheless, although forgotten even by most theater aficionados, such shows have remained vitally important to the most sophisticated contributors to contemporary musical theater. For example, John Kander and Fred Ebb drew upon the conventions of burlesque and the musical revue in both Cabaret and Chicago, while Stephen Sondheim and librettists James Goldman and James Lapine drew upon these works in Follies, adding an element of operetta in A Little Night Music.

Mordden also brings to bear a novelist’s eye for character. In Anything Goes we meet such engaging theater personalities as Lydia Thompson, the actor-manager who in 1869 horsewhipped a newspaper editor who had publicly chided her for her “use of disreputable language unrelieved by any wit or humor,” and who preceded Mae West and Sophie Tucker as an “independent wom[a]n who tested the legal limits of bourgeois protocols about gender.” In addition, Mordden introduces us to DeWolf Hopper, a successful comic who “nevertheless fielded a thundering basso profundo to send every lyric to the top of the house,” but whose memory has been overshadowed by that of one of his several ex-wives, failed actress and Hollywood gay-baiting gossip maven Hedda Hopper. And then there’s librettist-lyricist Harry B. Smith, who worked on over 300 shows, some of whose lyrics can still be counted on to “toot along with saucy charm” today.

Mordden offers remarkably detailed descriptions of the look and feel of productions to which fellow theater historians have little or no real access. In a recent interview Mordden described the wealth of material archived in the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, which he spends several days a week sifting through. Since the early 1980s, for example, it has become customary for producers to deposit in Lincoln Center’s collection a taped performance of every show that opens in New York City, thereby creating an unrivaled archive. But other of the library’s audio-visual resources go back as far as the mid-1940s, and Mordden has exhaustively studied every tape. He has also succeeded in identifying the script of Betsy, a Ziegfeld show with a score by Rodgers and Hart long thought to be lost, which he discovered among the yet-to-be cataloged papers of the great impresario.

He takes a moment in the introduction to express his gratitude to

the unique figure of the gay mentor, who in my case were former chorus boys and stage managers who carried with them a treasury of anecdotes and recollections and were glad of a new audience for them. My descriptions of shows that precede my own theatregoing owe everything to them, for, make no mistake, the chorus people have a larger perspective on a show than the leading players do, distracted as they [the leading players]are by the demands of their parts. And no one knows a show like its stage manager.

Questioned about this statement in a recent interview, Mordden described the scene that he found in Manhattan when he arrived there fresh out of college in 1969 at a moment when some Broadway shows could still afford to sport a full orchestra as well as both a singing and a dancing chorus. Because a dancer’s career is necessarily shorter than a musician’s or a singer’s, a male dancer often morphed into the company’s stage manager. Such theater stalwarts would share their professional war stories during gatherings at dinner clubs like Voisin.

Ever an attentive listener, Mordden learned how Fred Stone managed his impressive entrance in The Red Mill by falling backward down an eighteen-foot ladder (“padded trousers … gripped the ladder’s sides to control what appeared to the audience to be a sudden accident”), and how Gertrude Lawrence managed a seemingly impossible transformation during a momentary blackout in Lady in the Dark (as her character’s dream sequence “implodes in terror … Lawrence slipped offstage, leaving a double in … [a duplicate]costume to distract the audience while Lawrence breathlessly changed into street clothes to reappear seconds after the blackout, back in the psychiatrist’s office as if she had never left it”).

Anything Goes is a love song to musical theater by a scholar who has an encyclopedic command of the smallest details of each production’s history. For example, Mordden records that director-choreographer Bob Fosse himself had written the first draft of the book for Sweet Charity, “taking the sobriquet of ‘Bert Lewis’ (a play on his given names, Robert Louis). Realizing that he needed experienced help, he called in Neil Simon, giving Simon sole credit, but this occurred so late in the show’s gestation that the first song sheets came out with the Bert Lewis billing.” I was repeatedly struck by the justice of Mordden’s unexpected observations, such as those concerning the roots of My Fair Lady’s Ascot gavotte scene in Ziegfeldian extravaganza, or the pastiche construction of that play’s score (“the twee polka of ‘Why Can’t the English?,’ the soft-shoe ease of ‘I’m an Ordinary Man,’ which suggests an old music-hall song and dance”).

Deftly organizing a potentially overwhelming amount of factual information into a witty and smooth-flowing narrative, Mordden mentors his reader as generously and as gladly as he himself was mentored decades earlier by those onetime chorus boys and stage managers who revealed to him the tricks of the great stage magicians.

THE ROLE of the mentor in the evolution of gay culture is a theme that reverberates through Mordden’s fiction. Bud, the narrator of Mordden’s quintet of novels, repeatedly asserts that gay life is “an essentially civilizing force, like prep school or Peggy Lee albums.” He takes a particular pleasure “to introduce someone to something instructive or delightful that might—who knows?—change his life.” More importantly, he argues, the gay men who have migrated to post-Stonewall Manhattan are “cut off from our families of origin and the social system they champion or simply stooge for unthinkingly. We make our own families, invent our system. You need smarts to do that. So—education. The older among us kind of take care of the fledglings.”

The need “to help the newcomers” becomes almost a battle cry through the five books. And, much in the same manner as landlady Anna Madrigal selects renters who gradually coalesce into an alternative family in Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the City, Bud and his best friend Dennis Savage create on West 53rd Street a capacious household that shelters, among others, two naïfs newly arrived in Manhattan and in danger of being swallowed up by life on the street; a stud savant who occasionally sleeps on Bud’s living room sofa and brings a remarkably fresh moral perspective to the group’s affairs; a handsome publisher who leaves the closet in his mid-thirties and must learn to negotiate gay life at the height of the AIDS epidemic; and—as Bud finally passes into his forties—a clique of twenty-something Chelsea Boys to whom Bud serves as den mother and default sounding board.

Mordden offers, in effect, a modern take on the classical educational institution of pederastia, and one that has as far-reaching personal and social consequences as the ancient Greek model. Across the five books, onetime enemies bond in the kitchen as the more experienced Dennis Savage takes Cosgrove “stage by stage through some of his dishes” and the former street hustler learns the secrets of a very different “trade.” Abandoned months earlier by his own lover, Dennis Savage protests no longer “having some cute guy do some mystifying and troubling thing, then suddenly turn to me with that Peter Pan bewilderment where they hold on for dear life.” Attempting to explain a difficult encounter that Dennis Savage has had at a college reunion, Bud observes that “the truest friends are those who teach us something that matters greatly, even something with hard feelings in it: and those friends stay essential to us for life, not only part of our past but of our future as well. Our teachers are always with us.”

Although Mordden concluded his quintet with How’s Your Romance? in 2005, the last story of his new collection, The Passionate Attention of an Interesting Man, reunites Bud, Dennis Savage, Cosgrove and the final volume’s Chelsea Boys in a plot situation that seems contemporaneous with the action of Some Men Are Lookers (1997), the fourth volume in the series. No matter that the story may be a chapter excised from Lookers or Romance by an editor concerned about the book’s length: it is good to hear friends’ familiar voices again. In “The Food of Love,” Bud follows the progress of handsome, forty-something actor friend Alex’s affair with his female roommate’s emotionally domineering and presumptively straight boyfriend. Meanwhile, an acting class taken by Cosgrove and the Chelsea Boys allows Mordden to explore how gays generally address personal problems through role-playing, and more specifically how Alex can only learn his own sexual character through improvisation both on stage and off.

For Mordden, gay men only discover their true selves by first rejecting outright the roles imposed by straight society and then by improvising new ones. In his fiction Mordden continues to be fascinated by the creative ways in which gay society fashions and constantly refashions itself—that is, by the ways in which gay men are educated (by theater, by sex) and in turn educate “the newcomers.” In Mordden’s world, the same dynamic that governs the transfer of professional knowledge from stage manager to chorus boy to starry-eyed newcomer just off the bus from the wilds of Pennsylvania operates as well to protect the most vulnerable among us in gay society. As one of Mordden’s characters says, “Everyone teaches and everyone learns. That’s friendship, ace.”

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas.