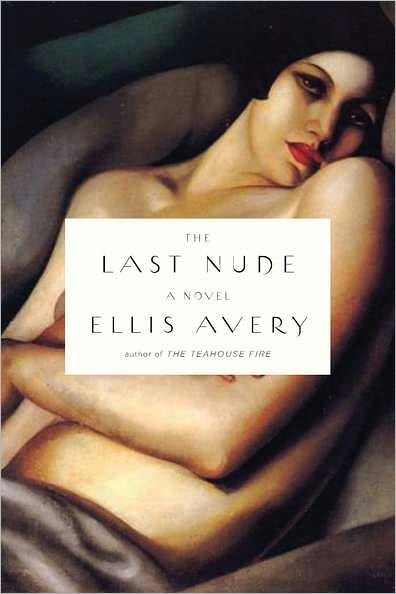

The Last Nude

The Last Nude

by Ellis Avery

Riverhead. 320 pages, $25.95

CLAUDE CAHUN, noted lesbian photographer of the 1920’s and 30’s, contended that lesbianism “occurs with special frequency in women of high intelligence.” In The Last Nude, novelist Ellis Avery gives Cahun’s notion of an “aristocracy of taste” quite a workout through Avery’s fictionalization of an erotic painting titled Beautiful Rafaela (1927), by Polish artist Tamara de Lempicka (1898–1980).

Avery, who teaches fiction writing at Columbia University and lives in New York City, became intrigued when she discovered that the last painting Lempicka was working on when she died was a copy of her 1927 painting of Rafaela. Inspired by Lempicka’s art, Avery’s curiosity led her to invent a reason why the enfeebled eighty-year-old returned to this image from the past, one that reconsiders the nature of the relationship between these two women.

Cassandra Langer, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in New York City.