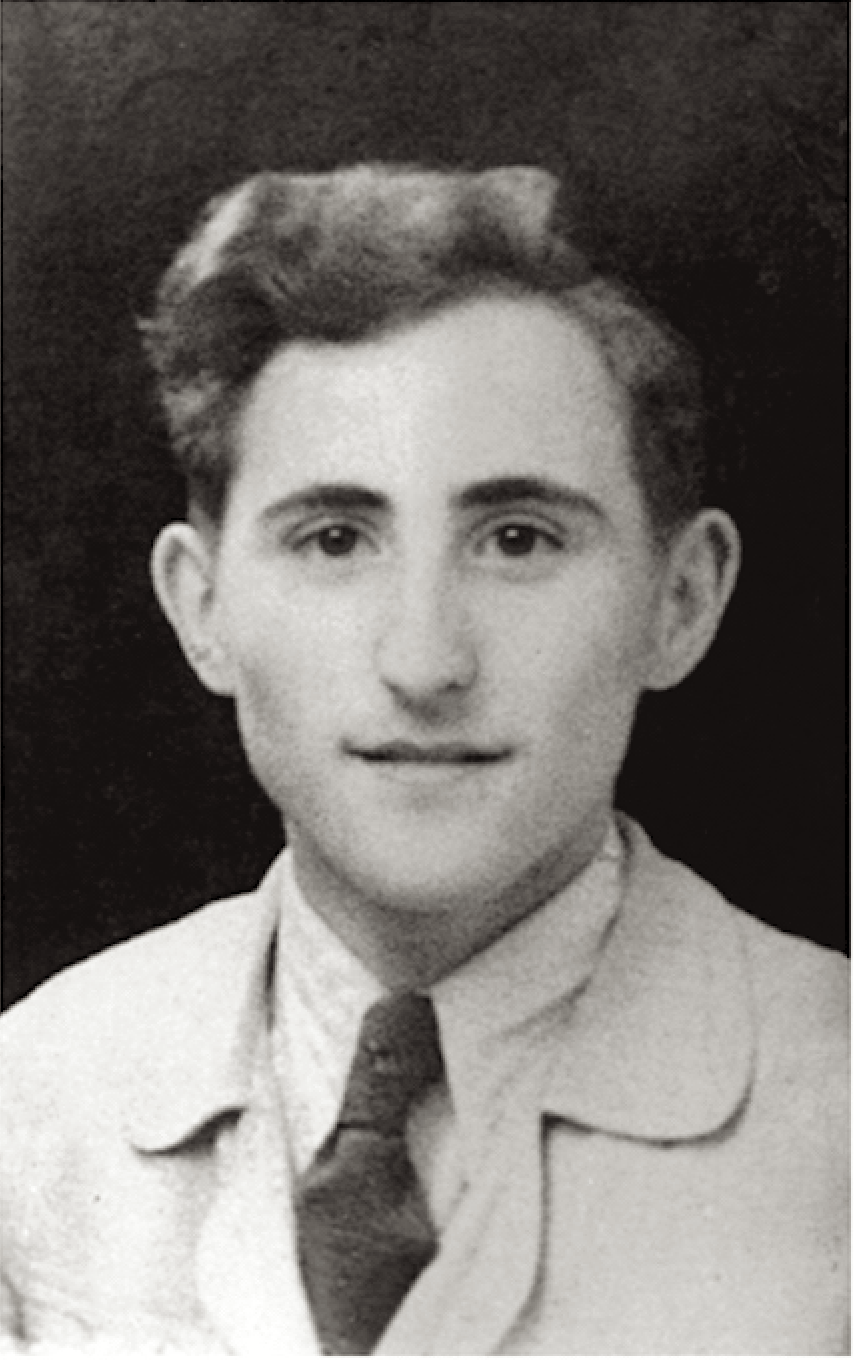

ANY DEFINITION of a “hero” has to be expansive enough to accommodate everyone from Achilles to Harriet Tubman, among many other well-known examples both fictional and historical. One person in history who isn’t well known, but who certainly fits almost any definition of a hero, is Gad Beck, who resisted the Nazis inside Germany during World War II and saved several dozen lives.

Beck started life as a gay Jewish boy (also short, slight, and nonviolent) and ended up leading the most successful resistance cell in Nazi Berlin—and he even survived the war. In fact, he lived until 2012, which means that if I had started my research on him just a few years before I did, I might have been able to meet him in person. During World War II, he won many small victories against the Nazis in the best of all possible ways—through bravery, a capacity to make (and defend) friends, and wit. In many ways, he was reminiscent of the mythical archetype of the trickster, which could embrace everyone from Homer’s Odysseus to the Norse god Loki.

He was born as Gerhard Beck in Berlin in 1923. (Gad is a Hebrew name that he chose for himself later on.) This was well before the rise of the Nazis, at a time when Berlin was quite progressive even by today’s standards. There was an atmosphere of religious tolerance such that a “mixed marriage” like that of Beck’s parents was neither uncommon nor frowned upon. His mother was a working-class Christian young woman who married her glamorous, Viennese Jewish boss. Both of their families were against the marriage, but they mostly got over it. Indeed, during the Nazi period, his mother’s family did everything they could to protect their sister and brother-in-law—and especially their nephew and niece, namely Beck and his twin sister Margot (later Miriam).

As children, Gerhard and Margot also went to regular state schools. Even after the Nazis took control, Beck’s parents, like most middle-class German Jews, hoped the anti-Semitic wave would just pass by. They instructed their son to keep his head down, ignore the bullying, and stay in his high school preparing for university. But this is where Beck’s character started to show: he didn’t want to conceal his identity. As soon as he heard there was a Jewish high school in the Scheunenviertel—the old Jewish neighborhood, later the Nazis’ ghetto—he wanted to attend, and he was much happier once he was there.

Beck was not interested in hiding his sexuality either, though he may not have had much choice. He seems to have been one of those gay guys with a feminine side that they can’t easily conceal. As a child, he didn’t like to roughhouse but did like to play with dolls. As an adult, he was what we might call a “swish”; sexually, he was a “bottom,” and a rather promiscuous one at that (but, like many people, he preferred cuddling above all else). What’s more, he was remarkably open about all this, starting with his first experience at age eleven, with a gym teacher, after which he didn’t hesitate to tell his mother about the encounter.

Over time, Beck would develop a set of attitudes that make him look remarkably modern—in fact, quite admirable even by today’s standards. While he could not have known today’s word “intersectionality,” he was a proud exemplar of it as one who belonged simultaneously to several disempowered groups. He had one Jewish parent and was the product of a mixed marriage; he was an effeminate homosexual; and he associated with the most marginalized elements of society. His friends included gypsies, prostitutes, the disabled—a panoply of victims of discrimination and bigotry. As a half-Jew from a bourgeois family, he did have a kind of privilege, but he didn’t want to take advantage of it; he always identified with the poor Jews of the ghetto.

This commitment is what came to the fore during the Nazi period. The Becks were in somewhat protected categories—Heinrich (Gerhard and Margot’s father) because he was married to an “Aryan,” and Beck and his sister because they were “Mischlinge” (half-breeds). They were all arrested in the Fabrikaktion of 1943, when Eichmann attempted to deport every last Jew or partial Jew from Germany, but along with many others they were released after dramatic protests by the “Aryan” wives and mothers (including Beck’s mother and aunts). In the end, only Beck himself was not released, and for his activities as a resistance leader rather than simply for being Jewish.

While his parents tried (broadly speaking) to lie low and just survive, Beck became ever more involved in his Zionist youth group, the Hechalutz, as it morphed into a resistance cell, protecting Jews who had gone underground to avoid deportation. Eventually, when the founder of the cell fled to Switzerland, Beck ended up running the group. By the end of the war, he was organizing support for 36 “illegal” Jews in hiding in Berlin, arranging new hiding places (when old ones fell through), securing ration cards or buying food for them on the black market, and so on.

Some of his exploits in this period were astonishing. Two in particular stand out for me, though there were quite a few others.

In the early 1940s, Beck fell in love with a boy called Manfred Lewin, whom he met in the Hechalutz. In fact, the story of how they fell in love is one worth telling. Those who know the Verdi opera Don Carlo will understand. They were chosen to read the roles of Don Carlo and the Marquis Posa in a staged reading of Schiller’s play (on which the opera is based)—a classic pair of “buddies” who could easily be boyfriends. So one thing led to another.

But in 1942, Lewin, who was Jewish on both sides, was taken for deportation along with his family. Beck’s response was not what you would expect. He raced to the paint business where Lewin had been doing forced labor and talked to the boss. It was a risky move, but Lewin had told him that the boss was just a regular German businessman, not a committed Nazi. He told the boss what had happened, and when he was sure that the boss was on his side, he told him that he wanted to rescue Lewin. And the boss did in fact offer help: he said that his son was out and that Beck could borrow his Hitlerjugend uniform to gain entry into the holding camp. So Beck put on the uniform—several sizes too big—and went down to the Scheunenviertel. He made a few “Heil Hitlers” and asked to speak to the commandant, whom he proceeded, as was his style, to bullshit. He told him that Lewin worked with him renovating apartments and had failed to turn in keys that his company needed. He had to take Lewin back to have him show them which key was for which apartment. He would bring him back soon: “What would I want with a Jew?” he asked.

Amazingly enough, it worked. The commandant let him walk out of there with Lewin. It didn’t matter much to him, and Beck was careful not to seem too excited. Truly a triumph worthy of Odysseus! True to form, Beck had it all planned out. One of his Christian uncles had built an air-raid shelter at his country house, so Beck and his sister could hide there, and he told Lewin to go there and wait for him. But this is where the rollercoaster goes back down. It was only 1942. Most people didn’t know about death camps, and Lewin didn’t think he could abandon his family to face deportation to a work camp in Poland without their strong, young son. So he insisted on going back—to his death, as it turned out. His whole family was murdered at Auschwitz.

The other of Beck’s amazing feats took place in 1945, after the Gestapo finally caught up with him. They found the apartment where he was staying with a later boyfriend and collaborator, Zwi Aviram, and arrested them in the middle of the night. Stupidly, Beck had kept extensive records of the money that they had used to support their “illegals”—money collected by Jewish organizations and transmitted to them via Switzerland. So the Gestapo had a ton of information to question them about. Yet Beck managed to deceive them again. They made him write a confession, and he went all the way, writing thirty pages about all the diplomats and Jewish organizations that had helped him—but he carefully avoided mentioning anyone who was still in Germany.

The Gestapo tried everything to get more complete information—including the trick Baron Scarpia uses in Tosca, that of having Aviram beaten in a nearby room while questioning Beck. But they couldn’t break either of them. Beck even managed to throw them off by using his social skills. By an extraordinary coincidence, the torturer who was questioning him—with brass knuckles on the table between them—whose name was Erich Möller, was an old family connection. Before the war, Möller and his wife had run a newspaper stand that Beck’s father supplied with cigarettes, and they were particularly kind to Beck and his sister. Beck managed to find a moment in the interrogation to remind Möller of their acquaintance.

Is that what saved them? No one knows. They may just have been left alive because the Allies were closing in on Berlin, and Beck was well known in resistance circles, so the Gestapo men were afraid to kill him. In any case, somehow they survived until the Red Army arrived and liberated them. Indeed, Beck lived to a ripe old age, and Aviram is still alive and living in Israel.

The heroism of Gad Beck deserves to be remembered and celebrated. He was an underdog in almost every way. Small and slight, he was a member of two minorities that were destined for extermination under the Nazis. But instead of trying to hide his identities, he stood up for himself and for his people. His only weapons were quick thinking, a knack for storytelling, and excellent social skills, which he brought to bear against the Nazi extermination machine, saving himself and two boyfriends (though one of them not for long), and 36 other German Jews.

Andrew Lear is a gay history scholar and president of Oscar Wilde Tours. He is developing a biopic about Gad Beck.

Discussion3 Comments

I loved this. Thank you for providing his story, and with such detail.

I wonder if the author realizes that the name Gad that he describes as having been chosen by Gerhard, is a short version of Gedallia, a man’s Hebrew name, and that although in Orthodox and Conservative Jewish tradition, you are considered to be Jewish if you have a Jewish mother, in Germany where the Reform movement had its roots, children of a Jewish father were recognized as being Jewish. It is therefore possible that he and his sister were given their Hebrew names by their father , which is where Gad and Miriam may have been derived! For example we had an Uncle who in public school and in civil records in Europe was know as Hans but had the Hebrew name Asher and by the late 1930’s started only using his Hebrew name, Asher.

Hi, that’s interesting, but I happen to know that Gad picked the name Gad when he joined Hechalutz.