PENISES IN ART are a bigger theme than you might think. After all, what is the number one question people ask in the Greek and Roman collection of any museum? There is no competition: why the penises in Classical art so small? And the second most-asked question is undoubtedly: is it true that the reason so many male nude statues are missing their penises is because the Christians lopped them off?

The answer to the first question is actually pretty clear. The Greeks saw penises as symbolic of masculinity (naturally enough). What’s distinctive about Greek culture is that the most important masculine virtue was self-control. In their eyes, a smaller penis symbolized this virtue, while a large or erect penis showed lack of self-control. There are speeches in ancient comedy that make this crystal clear, but it’s conspicuous in the art itself. Heroes like Hercules have tiny penises, while comic and shameful half-human creatures like Satyrs and Silenus have large, often erect penises.

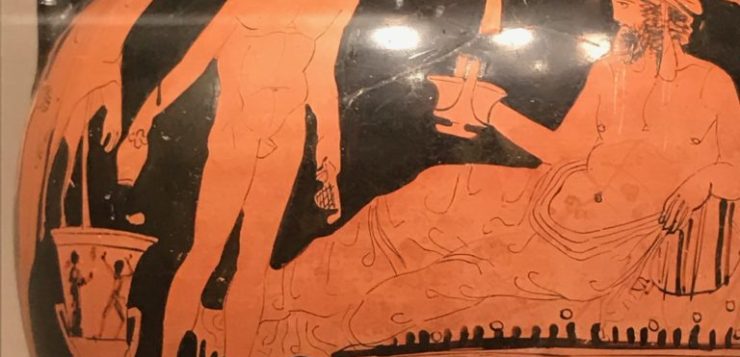

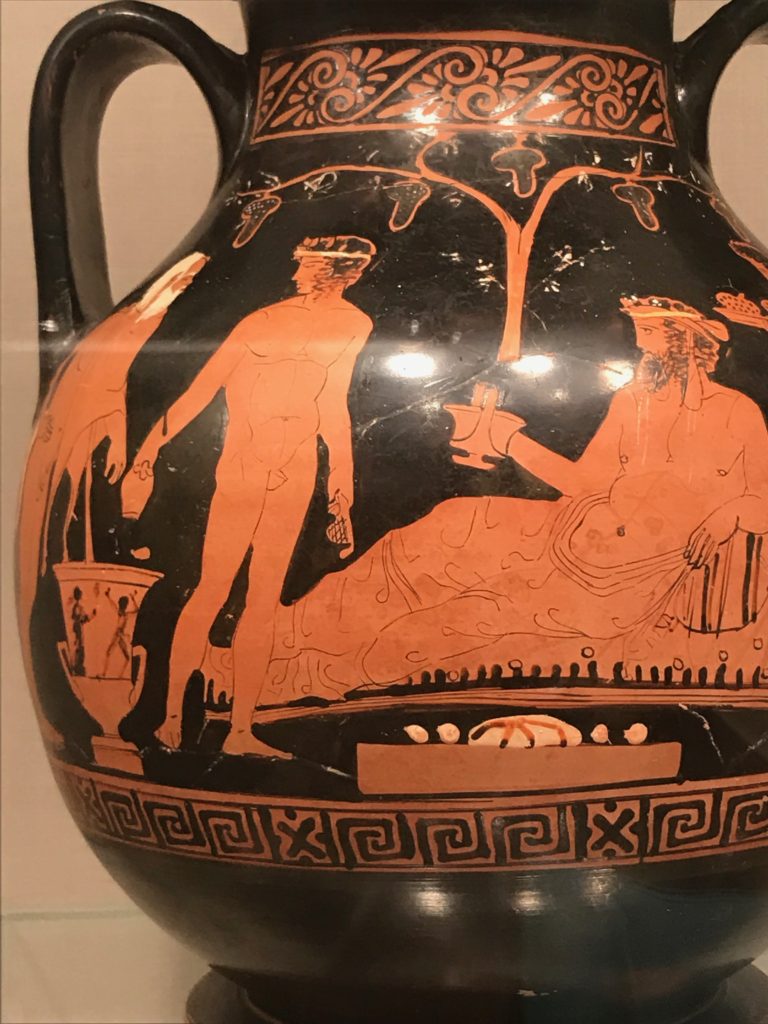

Some examples of these phallic conventions can be found in New York’s Metropolitan Museum. In one, an attractive adolescent boy is serving wine to a seated Bacchus. He has the penis that corresponds to beauty and youth in Greek art: the penis of a child. Not far from him is a little oil flask shaped like Silenus, the eldest of Bacchus’ followers. He is balding and ugly and has a grotesque, drunken expression. He has a large, messy-looking penis.

In everyday life, Greek men saw each other naked far more than men in most cultures, because at least the wealthy spent a good part of the day working out in the nude at the local gymnasium. In fact, gymnosmeans “naked,” so the gymnasium is the “naked place.” So if their eyes were open, they would have noticed that penises—like other body parts, only more so—vary in size; and this variation does not correspond to their owners’ moral or ethical character. This was a cultural convention, in other words, that presumably did not expose the well-endowed to moral judgment at their local gym.

The answer to the second question is more complicated. Most of the ancient statuary we have is marble (since bronze statues were mostly melted down in the Middle Ages) and damaged. The penis, like the nose, is one of the most fragile parts of a marble statue. So they could just have been damaged over time.

On the other hand, early Christians did deface statues of the gods, especially sexy statues, so they may have broken off some penises. On the whole, I think Christians generally defaced statues with chisels, so chisel marks could be a sign. I think for instance that the nose of the bust of the Emperor Hadrian’s boy-toy Antinous at the Met may have been chiseled off by Christians. Hadrian declared Antinous a god when he died, and Christians were particularly outraged at the idea of the boy-toy god. I do not believe that Christians broke off any of the missing penises at the Met, though there is no definitive proof either way.

There are in fact a lot of other fun facts about penises in art. The Romans, for instance, thought of erect penises (or at least sculptures of erect penises) as good-luck charms, so they hung little multi-penis wind-chimes (as it were) in their houses to ward off the evil eye. In the image shown here, the object is a penis with a penis, and a penis for a tail too. And penises also appear in the art of other periods, as in the vastly exaggerated codpieces that men wore in the Renaissance to proclaim their towering masculine powers.

To find out more, come on the Unhung Heroes tour of the Met on Sunday September 13, and for more online events – visit Oscar Wilde Tours Zooming Through Queer Culture.