I FIRST CAME TO KNOW the artist Bernard Perlin not through one of his extraordinary paintings, but through an exquisite photographic portrait taken of him in 1940 by the legendary photographer George Platt Lynes. That portrait, included in a book of Lynes’ photography that I acquired about a decade ago, shows a 21-year-old Perlin standing in his shirtsleeves, one arm flung up over his forehead, with languid eyes peering out beneath. I was instantly beguiled and thereafter haunted by this mysterious figure, about whom very little information was then available, aside from some images of his own evocative artwork.

Compounding the fascination for me was the fact that I had found the name of this mystery man, Bernard Perlin, threaded through all of the books I was then reading about the illustrious gay social and artistic circle of which George Platt Lynes had been a part from the 1930s through the 1950s. It seemed that Perlin had been intimately connected with this great New York gay “cabal,” whose members and visitors had included such artists as Paul Cadmus, Jared French, George Tooker, Pavel Tchelitchew, the impresario Lincoln Kirstein, and such literary figures as E. M. Forster, Somerset Maugham, Christopher Isherwood, Glenway Wescott, and Truman Capote. I soon came to discover that Bernard Perlin was the last living member of this extraordinary company.

The fortuitous purchase of a beautiful Perlin drawing a few years later gave me the impetus (and excuse) to finally reach out to him. He answered my “fan letter” with a phone call that left me completely in his thrall. Bernard, I quickly realized, was a storyteller the likes of whom I had never before encountered. After a flurry of convivial phone calls and letters, I was summoned to his home in Connecticut.

At age 92, Bernard was every bit the venerable yet mischievous old character I’d imagined him to be. That I kept up with his increasingly salty stories and scotch drinking until 3 a.m. our first evening together won me his respect and trust. There would be many such evenings to follow over the next three years. I began recording and transcribing our conversations from the outset, hoping to preserve the rich story of his life and times as told in his own colorful way. Sparked by Bernard’s desire to re-examine his life’s work, I also began tracking down and learning all I could about his art, which hung in major museums and private collections. A book about Perlin began to take form almost immediately, but so too did something completely unexpected: an education in how to live life to its fullest.

What I learned from the time I spent in his company was that in his life, as in his art, Bernard was an inveterate explorer, someone who reveled in pushing social, sexual, political, and creative boundaries. Shifting styles and themes often throughout his long career, he rejected the labels that critics, curators, and art historians often used to classify his art (such as “social realistm” “magic realism,” “romantic realism”). That he was a gay artist was never in doubt. He told me it never occurred to him not to fully embrace and express who he was despite the anti-gay mainstream culture in which he started his career. Indeed, the pursuit of sexual adventure was a main preoccupation throughout his life, second only to his art.

Although he painted a wide variety of subjects, many for commercial markets, starting in the late 1930s he also daringly committed to canvas and paper scenes of underground gay bars, homoerotic images of servicemen, nude studies of hustlers, and portraits of others like himself who were openly gay. In his art as in his life, Bernard sought to promote a recognition and acceptance of homosexuality as being just another variety of normal human experience and expression.

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Bernard Perlin was born in 1918 in Richmond, Virginia. He was sent to art school in New York at age fifteen and had early success as a muralist for Depression-era public works projects. After being rejected for military service during World War II due to his professed homosexuality, he instead fought the war with his paintbrush, designing many now iconic propaganda posters for the war effort. He then became a war artist–correspondent for Life and Fortune magazines, embedding with commando forces in Nazi-occupied Greece and later covering the war and its aftermath in the South Pacific and Asia.

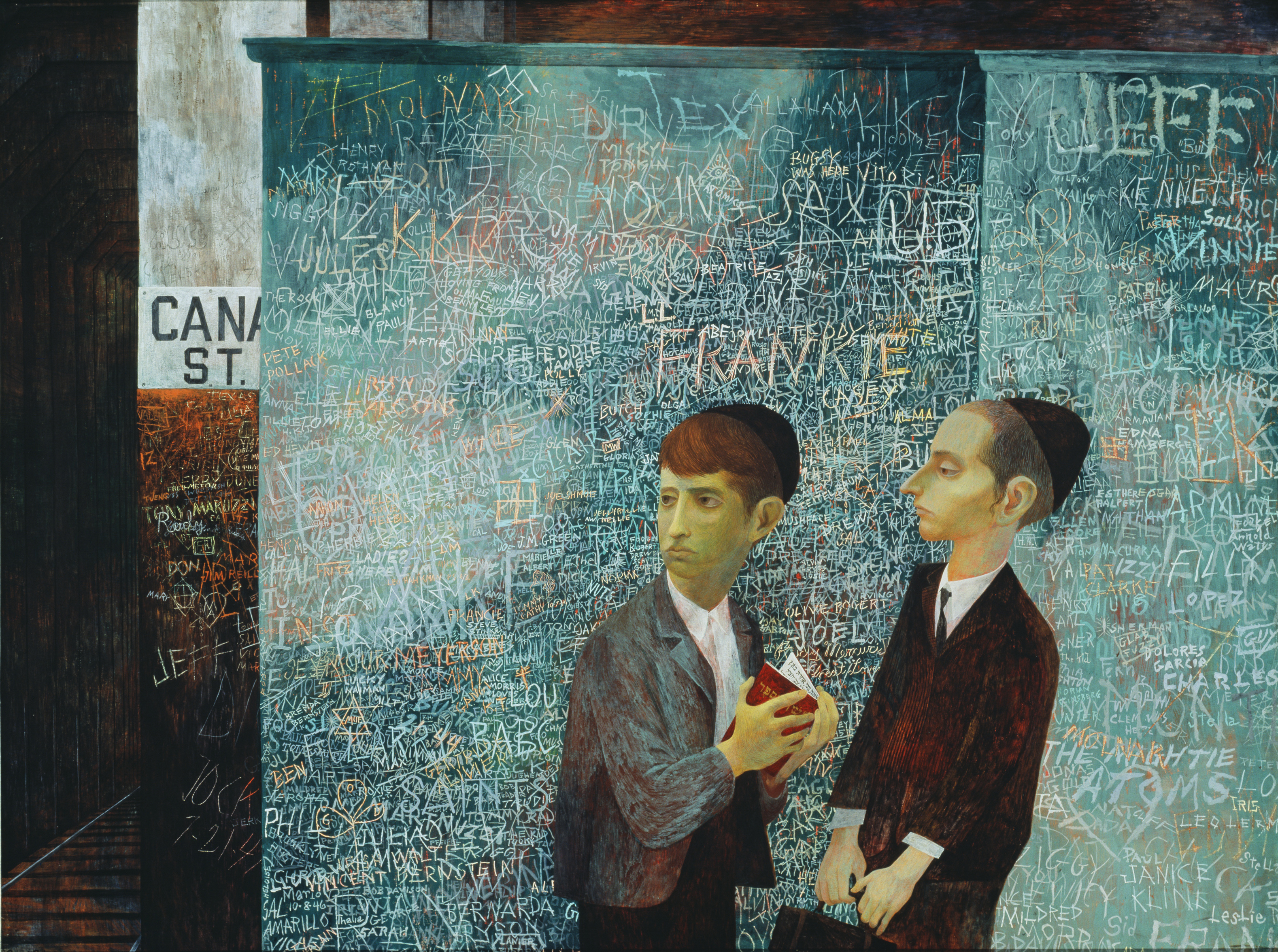

Returning to the U.S., Bernard embarked on a series of “social realist” paintings, recording scenes of life on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The most famous of these, Orthodox Boys (1948), depicts two Jewish boys standing warily on a subway platform under an intimidating wall of graffiti. With its references to the Holocaust and to continuing postwar prejudice on the American home front, Orthodox Boys established Perlin’s reputation in the art world. During that time, he was also becoming a successful illustrator for popular magazines such as Harper’s and Collier’s, continuing his commercial work well into the 1960s.

Bernard lived and painted in Italy from 1948 to 1953. There he began to move away from the realism of his previous work and instead painted, in his words, “beautiful pictures”: landscapes, still lifes, and figures in lush, sensuous colors and forms that lifted the “real” into the realm of the magical. It was this work that placed him in the company of other “magic realist” artists who “painted situations where magic was happening,” as the celebrated artist Peter Blake, a longtime fan of Bernard’s work, told The Guardian in 2012. “But rather than inventing the magic, it was a kind of everyday magic.”

Bernard also fully immersed himself in the “dolce vita” of 1950s Rome, chumming around with Truman Capote and Carson McCullers while competing with Tennessee Williams and Jean Genet for the attentions of the young men who hustled near the Spanish Steps. He was jailed in Paris during this period, as he had been back home in Virginia and Florida, for “behavior against public decency.”

He returned to New York to document the “cocktail culture” of the late 1950s, producing a remarkably bold series of “night pictures” that included scenes of jazz clubs, street boys, and underground gay bars—the last of which were very daring public works for the time. By now he was part of the upper echelon of New York gay society, a glittering “cufflink crowd” that included Leonard Bernstein, Jerome Robbins, Arthur Laurents, Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, Gian Carlo Menotti, Ned Rorem, and Gore Vidal.

Bernard left the New York art scene for Connecticut in 1959 and continued his work as a figurative painter for the next several decades. He took a long hiatus from his work following the devastating loss of a close friend to AIDS, but resumed painting for his own enjoyment in his nineties. In 2009, he legally married his partner of 54 years, Edward Newell. Still socially and sexually active at age 95, Bernard was at work on a new series of male nudes when he peacefully passed away in January 2014.

In Bernard Perlin, I was blessed to have observed someone who had the courage and ability to embrace and to dominate life. Bernard committed to canvas moments of his emotional memory, but in a manner that was illusionary and amplified, so that anyone who observed his art could feel something larger than life about it. He hoped viewers of his art would not only buy into the illusion but would also bring something of their own to it, that they would see themselves in a similar place or interaction and remember themselves there in the past. He marketed illusionary memories to excite in viewers a recognition of our shared experience as human beings. That’s where the magic truly comes into his art.

Michael Schreiber is curator for the Estate of Bernard Perlin. His new book One-Man Show: The Life and Art of Bernard Perlin is published by Bruno Gmünder.