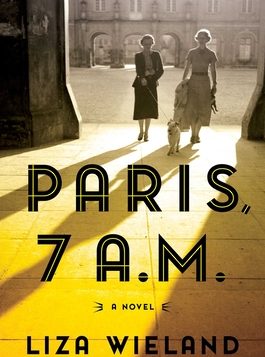

Paris, 7 A.M.

Paris, 7 A.M.

by Liza Wieland

Simon & Schuster. 333 pages, $26.99

PARIS, 7 A.M. is a quietly striking novel that imagines poet Elizabeth Bishop’s first trip to Europe in 1937. Having just graduated from Vassar College and still developing her talent, Elizabeth travels to France with three college friends. Staying in the Paris apartment of a friend’s mother’s acquaintance, she finds a city anxious about Germany’s actions. She befriends a worker at the German Embassy, suffers a terrible car accident that leaves a friend horribly injured, and performs a secret undertaking that she will never talk or write about to anyone.

Weiland takes her inspiration from the fact that, as she quotes from Brett C. Miller’s Elizabeth Bishop: Life and the Memory of It (1993), “Elizabeth’s journal breaks off” upon entering Paris in June 1937, “and the three women’s specific activities for the first three weeks in Paris are unknown.”

While the mission that she undertakes in France certainly provides moments of suspense, it is only one of many incidents of her life there. She bonds with her apartment’s owner, Clara, who’s still grieving over her daughter’s death and looks on Elizabeth as a surrogate daughter of sorts. In fact, Clara slowly and slyly recruits her for this job. In addition, Elizabeth receives terrible news about Robert, which fills her with guilt. She meets Sylvia Beach and visits her bookshop, overhearing a quarrel between Beach and her photographer friend. These scenes are so restrained that the car accident feels almost joltingly dramatic.

Homosexuality permeates the novel, rarely explicit but always present. Elizabeth has feelings for Margaret, even though Louise, a lesbian herself, tells her “it’s never going to change.” Sigrid, her friend from the German embassy, makes subtle reference to it while talking with Elizabeth. They later share an incredibly erotic scene. Vom Rath, a higher-up in the embassy, is frequently accompanied by a young Polish man.

Lovers of Bishop’s poetry will enjoy the many allusions to it in the novel, some obvious, others less so. Sections are named for her books, such as Geography III. Clara’s apartment, like the one in the poem, has clocks that all give different times. Elizabeth thinks about “The Man-Moth” when she finds herself “facing the wrong way” on trains. She remembers being told to “say goodbye to your cousin Arthur” at his funeral, as in “First Death in Nova Scotia.” Toward the end, the narrator lists everything Elizabeth has lost, including a watch, keys, “continents,” reminiscent of “One Art.” At the novel’s start, she thinks “Write it!” several times, a phrase at the end of “One Art.”

With short chapters and quick sentences, the book crisply imagines how Bishop’s French adventures could have shaped her life. It makes a powerful companion to Michael Sledge’s The More I Owe You, a fictional account of Bishop’s life with Soares.

Charles Green is a writer based in Annapolis, Maryland.