LOST BOYS

Amos Badertscher’s Baltimore

Albin O. Kuhn Library Gallery,

Univ. of Maryland, Baltimore

August 30–December 15, 2023

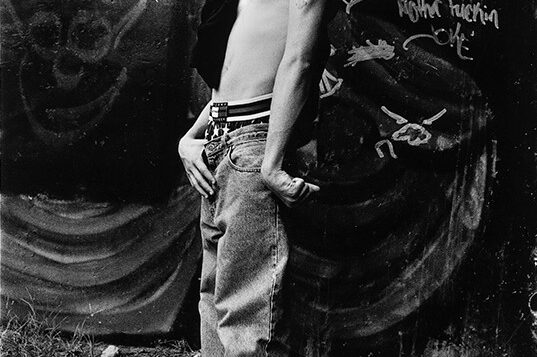

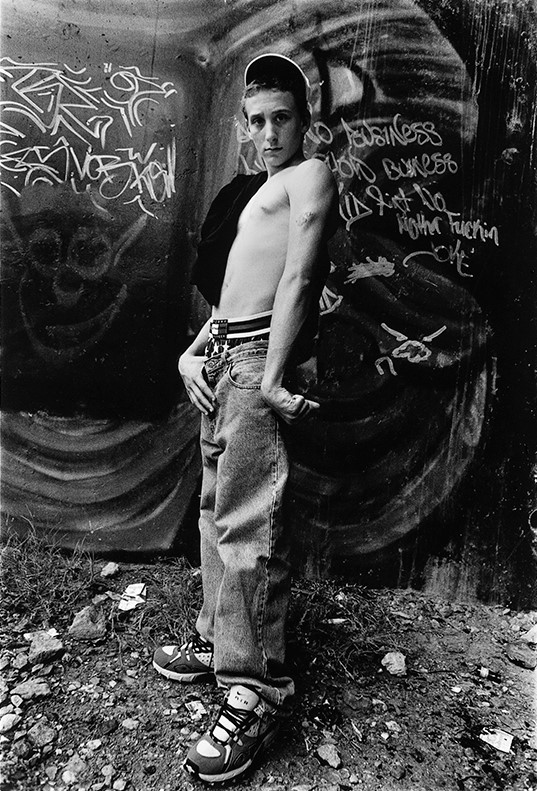

PHOTOGRAPHER Amos Badert-scher (1936–2023) captured the queer landscape of Baltimore from Eastern Avenue near Patterson Park, along Wilkens Avenue, and the Meat Rack on Park Avenue in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. His monograph Baltimore Portraits came out in 1999, and the recent exhibition Lost Boys: Amos Badertscher’s Baltimore in the Albin O. Kuhn Library Gallery at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, was the artist’s posthumous, first career retrospective. The exhibition included striking images of hustlers, club kids, go-go dancers, drag queens, drug addicts, friends, and lovers, and it established Badertscher’s centrality as an artist who documented queer Baltimore from the Stonewall era through the AIDS pandemic. He didn’t romanticize queer locations and the violence and risks: “I was forced to employ a number of eccentric and photogenic friends, gay and otherwise, and the ubiquitous teenagers who sold their bodies at an alarming number of locations throughout Charm City.”

LGBT people are diasporic, and migration is often necessary for survival, particularly at a time when same-sex sexuality and gender difference were not just unwelcome, but illegal. They fled to urban centers where they could lead anonymous, hidden lives. Without community, social, or political systems, most relied on interpersonal relationships and career pursuits. During the 20th century, before assimilation and gentrification, there emerged heterogeneous subcultures in urban neighborhoods in places like New York’s Greenwich Village, West Hollywood, Boston’s South End, Chicago’s Northside, Philadelphia’s Center City, 39th Street in Oklahoma City, San Francisco’s Castro Street, and Baltimore’s Mt. Vernon neighborhood.

Why the kids are out there on the street and homeless in the first place is the question few are asking. … The real answer to this problem is too elusive or painful to contemplate. Its roots are firmly embedded in the latent and active aggression of a capitalist order and in the blindness and bizarre ideology that allows our entire United States Congress, and executive branch, and justice department to sit in a city, just yards from the worst poverty, corruption, and disease in America.

In an essay titled “Photography, Sexuality, Community” in the 1999 collection Baltimore Portraits, Tyler Curtain writes: “The people who step into and out of the frames of these photos were his friends, lovers, erotic fixations, acquaintances, tricks, street kids, and pretty boys, who wanted attention and affirmation. Badertscher’s art takes the field, the excitement, of a trick and transfers it to the surfaces of the photo.”

Badertscher wrote handwritten notes on his prints, which are visual documents of human existence. For example: “Sandy the mild prostitute—at 18. Her haunt was Eastern Avenue. … [S]he died in September of 1993 of AIDS at age 32. Her real name: Steve Helmick.” And: “Steve: Big Daddy … street-wise with a short fuse.” And: “Tony. Death Angel. Attractive in a damaged way! This is what every genteel blue-collar mother warns her teenage son (or daughter) about. Rough trade!” And: “Elliott the antique dealer. This is certainly one of the true Baltimore crazies. … He dropped dead of a heart attack in the late 80s unencumbered by conventional moorings.” These are not mere annotations on the frames of Badertscher’s subjects, but living politics and realities, an engagement with photographic bodies. They breathe the conviction of a manifesto.

Steven F. Dansky, a documentarian and writer, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.