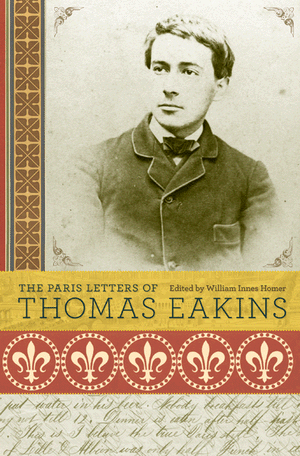

Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature

Inseparable: Desire Between Women in Literature

by Emma Donoghue

Alfred A. Knopf. 304 pages, $27.95

From the tales traded by Chaucer’s pilgrims to Jeanette Winterson’s gender-flipped contemporary classics, desire between women winks out from the pages throughout literary history. Inseparable serves, in the author’s words, as “a sort of map. It charts a territory of literature that, like all undiscovered countries, has been there all along.” Filtered through six categories that include coming out revelations, romantic rivalries, and cross-dressing that leads to mistaken same-sex desire, the book surveys works dating from the 12th century through the 21st. Emma Donoghue’s pedigree as a literary critic, novelist, scholar, and (it should go without saying) passionate reader makes her the perfect tour guide. Equally at home with Ovid and Rita Mae Brown, she is generous with her insights, providing helpful context as literary influences and social norms shift over time. The chapter concerning the “inseparables” of the title, devoted female friends in passionate, sometimes obsessive relationships, takes note of a romantic paradox: it makes sense to modern readers when a woman falls for a woman dressed as a man, because “opposites attract.” (Also, where else will you find a boyfriend with such fantastic skin?) Why, then, is there literary precedent for women to also fall for men dressed as women? As the author explains it: “[T]he classical model [of love in Renaissance literature]was the romantic bond between two men. Like calls to like; birds of a feather flock together.” Not all the relationships explored are sexual, and Donoghue remarks on the futility of trying to differentiate sexual relations from Platonic ones. Brilliant, insightful, and frequently funny, Inseparable is sure to bring new readers to the world of classic literature.

Heather L. Seggel

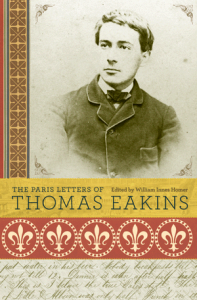

The Paris Letters of Thomas Eakins

The Paris Letters of Thomas Eakins

Edited by William Innes Homer

Princeton University Press. 342 pages, $35.

Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) is today considered one of the important American painters of the late 19th century. Because of his fondness for painting the male physique, often engaged in athletics, and because he showed no respect for the Main Line Philadelphia morality of his era, which led to his being dismissed in 1886 from his teaching post at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, there has been much speculation about his sexuality. This volume won’t resolve it. It brings together letters Eakins wrote to family and friends from 1866 to 1870 while studying art in Paris. Whether he took advantage of being far from home and living in sexually more liberated Paris to experiment, they do not reveal. But then, given his audience, it’s doubtful he would have mentioned such adventures even had he indulged in them. He does at one point remark to his father that a woman “is the most beautiful thing there is in the world except a naked man.” As has been repeatedly remarked, however, most recently by Axel Nissen in Manly Love: Romantic Friendship in American Fiction (reviewed in these pages, March-April 2010), “one of the losses of our current outlook is the ability to separate æsthetic appreciation of beauty—be it male or female—from sexual attraction.” The fact that Eakins considered male bodies more beautiful than female doesn’t prove that he was sexually attracted to them. The fact that he could write this to his father back in Philadelphia suggests that he didn’t think his family would deduce that either. One might expect that a young painter living in Paris at this time would have taken some interest in the revolutionary painters who were starting to make an impression, as it were, such as Monet. But Eakins studied with and idolized the Academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, who hated Monet and did what he could to obstruct his career, and he never mentions the Impressionists. Remarks the book’s editor: “Eakins himself must be seen as compulsively rational.” This book will be of interest to Eakins devotees but may have less appeal for the general reader.

Richard M. Berrong

Oscar Wilde might seem an unusual hero for a mystery. But as he says frequently in the third entry in this series, “the eye is the notebook of the poet—and the detective.” Taking place primarily from 1881 to 1883, during Wilde’s American tour and subsequent visit to France, this novel depicts the end of the La Grange acting dynasty. Edmund, the patriarch, meets Wilde on the boat returning to Europe, and hires him to work on their production of Hamlet. However, four murders among the cast and crew threaten the performance. The first, of Wilde’s former valet, prompts him to investigate. Many secrets are uncovered, especially concerning Edmund’s talented children. Despite the violence and dark subject matter, the novel is full of humor. Wilde finds many occasions to make some of his famous quips during the course of his investigation. His famous line “I have nothing to declare except my genius” becomes a running joke, with variations uttered to customs officials throughout his travels. One curious aspect of the book is that while it makes no mention of Wilde’s homosexuality, he enjoys many habits characteristic of today’s gay men. These include his wearing of flamboyant clothing, copious alcohol consumption, frequenting risqué nightclubs and bars, and even partaking of brunch. By novel’s end, Wilde appears to have solved the murders and even cleared the name of an innocent man. Yet the epilogue reveals a twist that throws everything into doubt, offering a disturbing but credible alternative solution. Oscar Wilde and the Dead Man’s Smile is an engaging, well-researched mystery, with a clever plot and large cast of famous characters, including Sarah Bernhardt, James Russell Lowell, and Arthur Conan Doyle. Charles Green In her first-person narrative Rebecca Cantrell depicts in dramatic fashion the life of Hannah Vogel, a crime reporter in Weimar Germany who writes under the alias of Peter Weill. Hannah is a socialist and despises the Nazis. Her gay brother Ernst is a transvestite who has been murdered at the novel’s start, setting up the whodunit aspect of the story. Hitler’s gay protégé, Ernst Röhm, who historically was the leader of the Brownshirts, figures prominently in the book as the former lover of Hannah’s brother and the father of a young boy, Anton. We also learn that Hannah and her brother have loaned their identity papers to their friends Sarah and her son Tobias, both Jews escaping to America. Before his death, Ernst had been kept by a lawyer named Rudolph von Reiche and had an affair with a Nazi named Wilhelm Lehmann. Hannah’s own love interest is Boris Krause, a handsome banker. The gay characters definitely get short shrift in this novel, either murdered or, in Röhm’s case, trying to rape Hannah, who has dressed up as a boy in order to attend an all-male Nazi party. Rudolph von Reiche is evil, Wilhelm is a Nazi boy wunderkind with a patriarchal monster of a dad, and Ernst is a cross-dresser with a hankering for all things red, who sings at the El Dorado, a gay club. A strength of the novel is Cantrell’s historical knowledge and imagination. She has designed a plot and an atmosphere that are well matched to the noir tones of the period. A weakness is that the author sometimes tries to include too much—too many characters, too many moments of high pathos and sentimentality. But the novel is sufficiently gripping to be an enjoyable reading experience. Walter Holland As this novel opens, Reginald Fortiphton, just out of prison and a term of house arrest, has found a job, having convinced a small publishing house to hire him to write a travel book about the northwest coast of North America. The result is a book within a book, as author Bruce Benderson leads us through Fortiphton’s maze of encounters with local characters as he writes Impressions of the Pacific Northwest. Fortiphton’s prose is heavily annotated by one Narcissa Whitman Applegate, whose editorial commentary on the main story, notably the author’s errors and misjudgments, runs at the bottom of most pages of Pacific Agony. Fortiphton’s adventures include the attempted seduction of one of his hosts, a married man; becoming sexually aroused at an art opening by a scantily clad young man; and meeting a hustler in Portland who desperately needs a bath and clean clothes, as well as money. If the leading character were a teenager, this might be called a coming-of-age novel; but Fortiphton is a mature man and it might better be called a coming-to-death novel. Fortiphton is old enough to be beyond heavy drug and alcohol use—or is he preparing for one last hurrah at life’s finish line? Despite some beautiful and witty writing, this novel doesn’t venture deeply enough into the lives and minds of its characters, many of whom go nameless. Reginald Fortiphton’s decline into depression (or other mental illnesses) doesn’t make him particularly good company for almost 200 pages. Nevertheless, some of the characters, such as the worldly Delilah and the mysterious (possibly criminal) Jukka a.k.a. Johnny, offer enough intrigue to keep the pages turning. David Ritchey Oscar Wilde and the Dead Man’s Smile: A Mystery

Oscar Wilde and the Dead Man’s Smile: A Mystery

by Gyles Brandreth

Touchstone. 365 pages, $14.

A Trace of Smoke

A Trace of Smoke

by Rebecca Cantrell

Forge Books. 300 pages, $24.95 Pacific Agony

Pacific Agony

by Bruce Benderson

Semiotext(e). 183 pages, $14.95