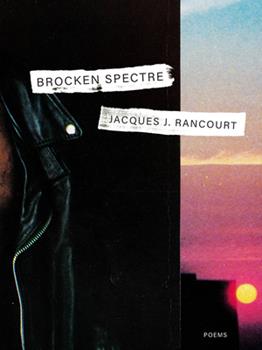

BROCKEN SPECTRE

BROCKEN SPECTRE

by Jacques J. Rancourt

Alice James Books. 102 pages, $18.95

TWO MEN HIKE to the top of a cliff. Cast on clouds of mist, their shadows appears huge and haloed. This is the optical phenomenon called the Brocken Spectre, the logical one explains. The sensitive one comprehends yet also wonders: Is this what a soul looks like? The poems in Brocken Spectre, Jacques J. Rancourt’s second full-length collection, document the evolving relationship between these two men, a doctor and a poet. On their first date, they walk through a San Francisco park. A man they pass crumples to the ground, seized by a heart attack. The doctor tries and fails to revive him, yet his valiant effort wins the poet’s everlasting admiration. This stranger’s death gives birth to their relationship.

Unfolding in the present day, this relationship stands in the long shadow of the AIDS crisis. Born “the year AZT was released,” the speaker exhibits a strange case of survivor’s guilt: “636,000 … of us died & I did not./ know a single one,” he marvels in “The Wake.” See what he did there with that period? He anchored his individual experience in the collective one. He is imprinted by grief for his lost gay forebears.

The poems struggle to make sense of this preoccupation. The speaker is aware that the glamorous sheen of the heightened past has a dangerous hold on him. He tries tempering his romantic notions with harsh statistics and realities. Yet his imagination transforms every subject it lights upon. Cruising parks and bathhouses are likened to places of worship, where sex is driven by the need for connection, absolution, and redemption.

The present day seems less epic, curiously stagnant by comparison, although it offers gay men the gift of living in “the easier century,” the speaker acknowledges in “Near the Sheep Gate.” Born twenty years earlier, “we might/ be counted among/ the dead.” Yet the present day carries its own threats. In “Mt. Diablo,” mortality is circled by the Californian wildfires. “A year ago/ I barely knew you & now I picture/ all the ways I could lose you,” the speaker reflects.

In “June 12th, 2016,” the morning after the shootings at the Pulse nightclub, the speaker’s mother gently inquires about his well-being. “I tell you that/ I live/ nowhere near Orlando,” he coolly replies, and one wonders if a kind of internalized homophobia has suddenly flung up its distancing walls. Yet it’s soon revealed that he’s preoccupied by a more immediate tragedy, the death of his beloved cat, “this critter I loved more/ than I love most people.” Animals, with their mysterious and innate understanding of the natural world, have a kind of sacredness in Brocken Spectre. Squid, eels, bullfrogs, and loons are just some of the many that appear.

Throughout the collection, the speaker frequently returns to the woodland scenes of his youth, where campfires, stars, and skinny-dipping convey all the innocence of Eden. There’s a suggestion that he, too, was driven out of paradise; gay men have always flocked to cities for safety, to discover themselves and one another. “In the Castro” finds the speaker and his lover on what feels like another privileged night out, “bored of mojitos.” Staggering from one bar to the next, the speaker suddenly imagines the marches and protests that once took place on these same streets: “There are moments I get lost/ in time,” he confesses.

In Brocken Spectre, the present moment is always haunted, not only by the past, but by the suggestion of something divine that can never be adequately named or proved. The poems grapple with questions of faith from the perspective of an uncertain believer. “Once, I believed in God,” he admits in “Golden Gate Park.” But for all his admitted uncertainty, that space where belief once stood inside him still feels largely occupied. All of the poems remain alert to evidence that there’s more to life than that which we can rationally perceive.

Gay men all experience being gay differently; it is also something we all share. In Brocken Spectre, the poet locates himself in both experiences. He throws his shadow on a misty past to see his divine self projected: large, inscrutable, and haloed by a rainbow. ____________________________________________________ Michael Quinn reviews books for literary journals, for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue, and for his own website, mastermichaelquinn.com.