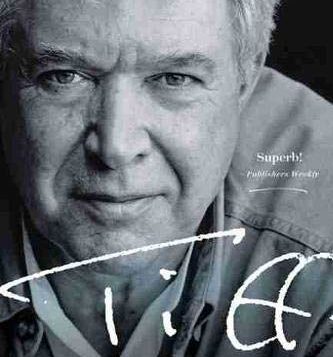

UNLESS you’re Canadian, older, or a scholar of 20th-century literature, you’ve probably never heard of Timothy Findley—the subject of Sherill Grace’s enormous and detailed biography. Yet he was a major figure in his time: actor, playwright, producer, much honored and best-selling author—almost until his death in 2002. He was openly gay in the media quite early on, and he made certain that his male life partner was included in everything public that he did. Yet he refused to be called a “gay author” and never wrote anything that can be said to add to LGBT literature as we know it. The few gay characters in his later books are often creepy or mentally disturbed—some prey upon teens, who, in turn, often prey back on them.

So, placing Findley as a writer becomes difficult. Although he came out to his parents at the amazing age of fourteen, and at times he was outspoken for gay rights and AIDS care, it is more crucial that he was alcoholic and probably bipolar. His boundless ambition, intelligence, and talent for the stage placed him in the Stratford Shakespeare Festival early on. It led to connections like Tyrone Guthrie and Alec Guinness, who got him stage and TV acting work and connections in England as well. Even so, and despite writing a dozen plays for various media, the theater wasn’t his real milieu; the written page was.

Findley’s third novel, The Wars, (1977) based on his uncle’s World War I experiences was raw and anti-war, shocking to a nation dedicated to “doing the honorable thing,” i.e., sacrificing its sons for England. But he wasn’t merely a provocateur. He waited until 1995 in The Piano Man’s Daughter to write about his mother’s unconventional, wildly dysfunctional family. Three novels of the 1980s—Famous Last Words (1981), a best-seller: once available as a Dell paperback; Not Wanted on the Voyage (1984); and the post-Watergate The Telling of Lies (1986)—are his most original, entertaining, and literary books. Later novels like Headhunter (1993) and Pilgrim (1996) pick up themes from his 1960s novels, namely The Last of the Crazy People and The Butterfly Plague.

Mental health and illness were a subject in his family history, in his own life, and in his work. He had a therapist for decades, and his “ill” characters are among his best written. But Findley seemed less interested in his characters’ growth through experience than in locating and focusing on the precise place and time where their interior worlds met, matched, or utterly collided with that of the world around them. For some readers, Noah’s cat in Findley’s ark tale, Not Wanted on the Voyage, may be the perfect synopsis of Findley’s “center of consciousness”: amoral, unethical, sharply observant, ferocious when crossed.

It is unclear exactly where Tiff stands in any canon. But if you love big, well-researched, and more-or-less objectively written biographies—including 112 pages of bibliography, indexes, and family trees—this book could be just what you’re looking for.

____________________________________________________

Felice Picano’s latest fiction is Justify My Sins: A Hollywood Novel in Three Acts (Beautiful Dreamer Press).