NEVER ANYONE BUT YOU

NEVER ANYONE BUT YOU

by Rupert Thomson

Other Press. 368 pages, $16.99

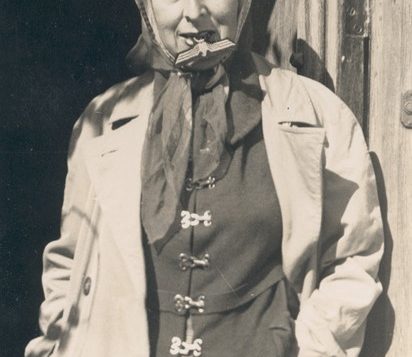

CLAUDE CAHUN and Marcel Moore—née Lucie Schwob (1894–1954) and Suzanne Malherbe (1892–1972)—were a pair of artists who befriended and worked among some of the most important artists and writers of the 20th century, and they not only endured but participated in the century’s most consequential war. The two women left behind their own original artistic record and managed to sustain a nearly fifty-year relationship to boot.

Rupert Thomson’s fictionalized depiction of their relationship, Never Anyone But You, begins with a glimpse of their lives in 1940:

Claude and Marcel knew each other as teenagers and had already developed a mutual attraction when—in what must be seen as a remarkable stroke of luck—Moore’s mother married Cahun’s father. Now stepsisters living under the same roof, they had an excuse to maintain their closeness while hardly raising any suspicions.

Perhaps Thomson felt the two women’s lives were simply too full to skip over any of their time together. The cost of covering sixty years is that the narrative rarely goes too deeply under the surface of their relationship. Thomson’s decision to have Marcel narrate the novel means that its principal focus is the abiding object of her interest and desire: Claude Cahun. Through Marcel’s eyes we watch Claude flirting with a man that she may or may not have had an affair with. We witness Marcel trying to talk the impetuous Claude out of doing various things that she’s contemplating, including suicide. Marcel Moore, who became an accomplished photographer, took many photos of Claude during their life together—a perfect metaphor for their relationship in this novel.

There’s no ignoring the fact that the two women rubbed shoulders with some of the intellectual and artistic luminaries of their day, from André Breton and Robert Desnos to Salvador Dalí and Ernest Hemingway. But the snapshots that comprise so much of the book never seem sufficient to set up a cohesive plot. Claude and Marcel are friends with artists; Claude is trying to make a name for herself in Paris; the war is approaching; they flee to the Isle of Jersey to escape. Their love story provides something of a narrative thread, but it’s too episodic to provide an overarching through-line on which to hang these events. Things seem to just happen around them as Marcel watches and does her best to protect Claude from reckless decisions.

Never Anyone But You is strongest once the two women retreat from Paris for Jersey and set up house away from the war. The third section, “Self Portrait,” presents the most meaningful exploration of their mutual connectedness as opposed to a one-way observation. Only relatively late in the game, at a crucial moment after the two women have been captured by the Nazis for their role in resisting the occupation, does Thomson fully allow us to see what the two women mean to each other. Other than that, the novel rarely takes the plunge to reveal the love between Marcel and Claude, settling instead for a same-sex romance about one woman and the object of her devotion.

____________________________________________________