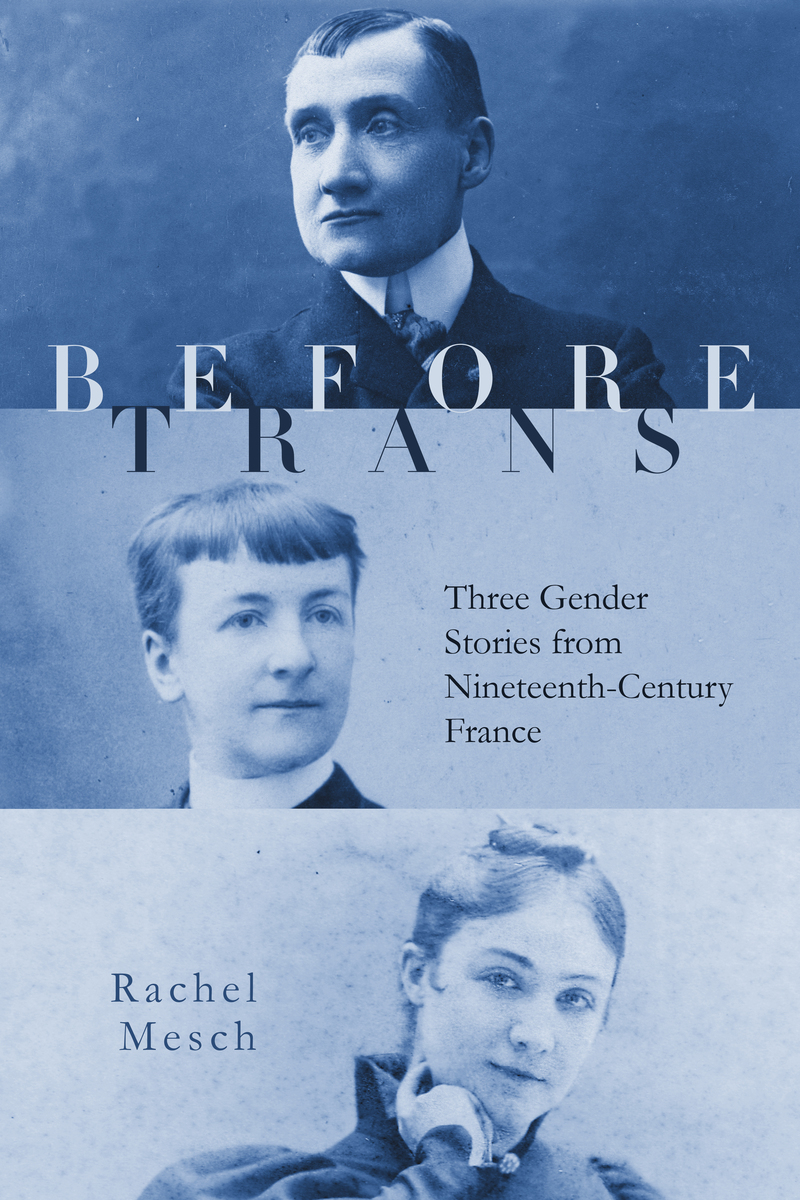

BEFORE TRANS

BEFORE TRANS

Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

by Rachel Mesch

Stanford Univ. Press. 333 pages, $30.

MARIA was a shy, bright girl growing up in East Los Angeles. According to her mother, there was nothing unusual about her gender presentation in elementary school: she liked dolls, her long hair, dresses, princess costumes for Halloween. (Names and details have been changed to protect anonymity.) Mother and child agreed about that. It was only in middle school, with the start of puberty, that Maria started to feel there was something deeply troubling about her body and how she felt in it. After watching a female-to-male trans teen on YouTube, Maria started to figure out that he really felt like a boy and that “trans” was the term to describe this. There followed two years of quiet struggle, gradual adoption of male clothes, and increasing hostility from peers. After trying on a couple of boy’s names, he settled on Eddie. In the meantime, he switched schools twice due to teasing and an assault (ironically, because he got bullied as a “fag”).

Despite the proliferation of trans celebrities and characters in diverse media, it can still be a turbulent, even perilous, process for a person with atypical gender feelings to develop their gender identity and sexuality. Medicine only formulated the concept of “transsexualism” in the first half of the 20th century. This diagnosis and its treatment with hormones and surgery were codified and legitimized in the second half (after the manufacture of sex hormones). While the medical model was being standardized, individuals with diverse gendered feelings were busting through that model by the 1990s, leading to a multiplicity of identities and terms: transgender, genderqueer, gender fluid, gender nonbinary, non-transitioning transgender, and so on.

Before the 20th century, what would a Western person with trouble conforming to gender norms have done without any of these terms? They may have suffered silently. They may have discretely “passed” in their desired gender role—until being exposed in life or at autopsy. They may have brazenly violated vestiary conventions and laws. Many of these stories have recently been detailed by scholars (such as the late Leslie Feinberg) as examples of “transgender warriors” from antiquity to the present. However, it is problematic to lump all of these manifestations of gender diversity as exemplars of our contemporary category of “transgender.” The historical characters did not have this identity label, and, like many a queer teen today, may have actively resisted being lumped under any category.

In her new book Before Trans, Rachel Mesch adroitly walks the methodological tightrope of examining historical characters through the lens of transgender analysis, yet accepting their gender originality. Her writing is theoretically savvy without being academically ponderous. A professor of French studies at Yeshiva University, Mesch has previously studied French women authors of the Belle Époque. In her current book, she brings to life three gender-bending women of the period: Jane Dieulafoy, Rachilde, and Marc de Montifaud. There is a wealth of Rachilde scholarship by feminists—despite the fact that Rachilde disavowed the label. The other two women are more obscure, though visitors to the Louvre might recognize the monumental finds from Dieulafoy’s Persian excavations. Mesch refers to her three subjects as “women” because that is how they identified themselves, sometimes explicitly dismissing the aspersions cast upon them by journalists or rivals who viewed them as mannish feminists, “New Women,” or “bas-bleu.” (Bas-Bleu—“blue-stocking”—remains a pejorative French term for women with literary or intellectual pretensions.)

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and Associate Clinical Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UCLA.