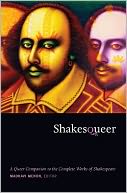

Queer Shakespeare: Desire & Sexuality

Queer Shakespeare: Desire & Sexuality

Edited by Goran Stanivukovic

Bloomsbury. 402 pages, $80.

WAS SHAKESPEARE GAY, or perhaps bisexual? If so, was it in the way that we think of gay or bisexual today? Or was he being trendy, playing games with Elizabethan literary and high society, the way David Bowie and Prince exploited gayness in the 1970s and ’80s ? If the latter is true, what do Shakespeare’s poetry and plays actually say on the matter? We’re pretty sure that his contemporary Christopher Marlowe was homosexual, but what about the Bard?

The question is more than idle curiosity, and not only because of Shakespeare’s standing in the literary world and his continued influence in the performance world. The very fact that boys and young men were trained and hired to perform the parts of women in his plays has to be significant on some level. This new compendium contains two essays about a 2016 British production of A Midsummer’s Night Dream in which one of the women’s roles was played by a man—apparently hot stuff in the academic world. And yet, this modern switch seems a slight innovation. One wants to protest: People, all of the females were originally played by males! Think of it, some acne-faced lad was actually the first Lady Macbeth. Another boy was the original Cleopatra, subject of the lines “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale/ Her infinite variety.” Regan, Goneril, Beatrice, Juliet—all boys.

Over a quarter of Queer Shakespeare’s pages are devoted to notes, bibliography, and an index. The editor’s introduction gives warning that they will use the word “queer” not as we do, because that would “signal marginality” and also “privilege the avant-garde” (that’s you, reader!). Instead it is being used in a new, broadened sense that includes not only language and objects, but also intent and meaning and place and environment and even weather. In other words, everything is queer. So the next time someone comes at you wielding a baseball bat yelling “queer,” he’s not calling you a faggot but instead an immanence of the universe.

If you love reading essays that bring up interesting aspects or moments in the Bard’s work, this book will not disappoint. The best ones make up a little more than half of the book, with odd yet often intriguing headings like “Romeo & Juliet and the Promiscuous Seductions of the Plague,” where it is disease rather than any single outbreak that is being studied. “Queer nature, or the weather in Macbeth” is pretty much a given: stage, film, and opera directors have had a ball with all the strange goings-on in the play, none more than Akira Kurosawa in Throne of Blood. “Strange insertions in The Merchant of Venice” is about Antonio, whose predicament is solved by Portia but whose exact relationship to the man she marries not only incites the action but also, by the end of the play, still remains a mystery.

“Two Lips, Indifferent Red: Queer Styles in Twelfth Night,” by the editor himself, and a piece with my favorite title, “Antisocial Procreation in Measure For Measure,” by Melissa E. Sanchez, are another matter altogether. These might have been intriguing had they actually addressed their announced topics. Instead we get, in the piece by Sanchez, a sentence like this: “In this chapter, I want to place Edelmann’s important challenge to reproductive futurism in conversation with recent new materialist work that stresses what Jane Bennett calls the ‘vitality’ of matter in order to ‘dissipate the onto-theological binaries of life/matter, human/animal, will/determinant and organic/inorganic.’” It appears to be English, but I defy anyone to tell me what it means. True, it is taken out of context, but alas the context is even more mind-numbing and hardly clarifying. And what does any of it have to do with Shakespeare’s play, sexuality, or desire?

John Madden’s popular, Oscar winning-film Shakespeare in Love (1998) also explored gender issues in Shakespeare, as well as desire and sexuality. A high society young woman wants to be an actor at a time when women were not allowed onstage. She fabricates an identity as a boy actor, is hired, acts briefly, obtains the love of Will, and is found out. But Madden’s genius in the film is his choice of the two lead actors: Gwyneth Paltrow as the girl pretending to be a boy is tall and gangly, with a squarish face more handsome than pretty. She passes easily as a boy. Joseph Fiennes as Will is lean and compact, with lustrous, brown eyes, a bow-shaped mouth, and a thin oval face, accentuated by his meager goatee—just like Nicholas Hilliard’s portraits of stylish young noblemen of the time. In other words, she’s butch and he’s femme. It completely upends our romantic expectations, and in so doing it actually earns that much misused and overused term, “queer.”

Felice Picano’s latest book is a memoir titled Nights at Rizzoli (OR Books).