IN HIS RECENT, RICH BOOK Love’s Next Meeting: The Forgotten History of Homosexuality and the Left in American Culture (2021), Aaron S. Lecklider summarized its subject in a single line: “The vigorous opposition to homosexuality in American culture was often recapitulated on the Left.” So it was, “often”—but not uniformly, as Lecklider himself documents. Particularly in the 1930s to the ’40s, some heterosexual lefties (the number can easily be exaggerated) regarded homosexuals as at least potential allies, as members of the dispossessed class in its struggle against capitalism. Yet the fact remains: the Communist Party USA was for most of its history culturally conservative, with known homosexuals discouraged from joining or booted out once discovered. Socialism, on the other hand, has at various times in its history been far more welcoming.

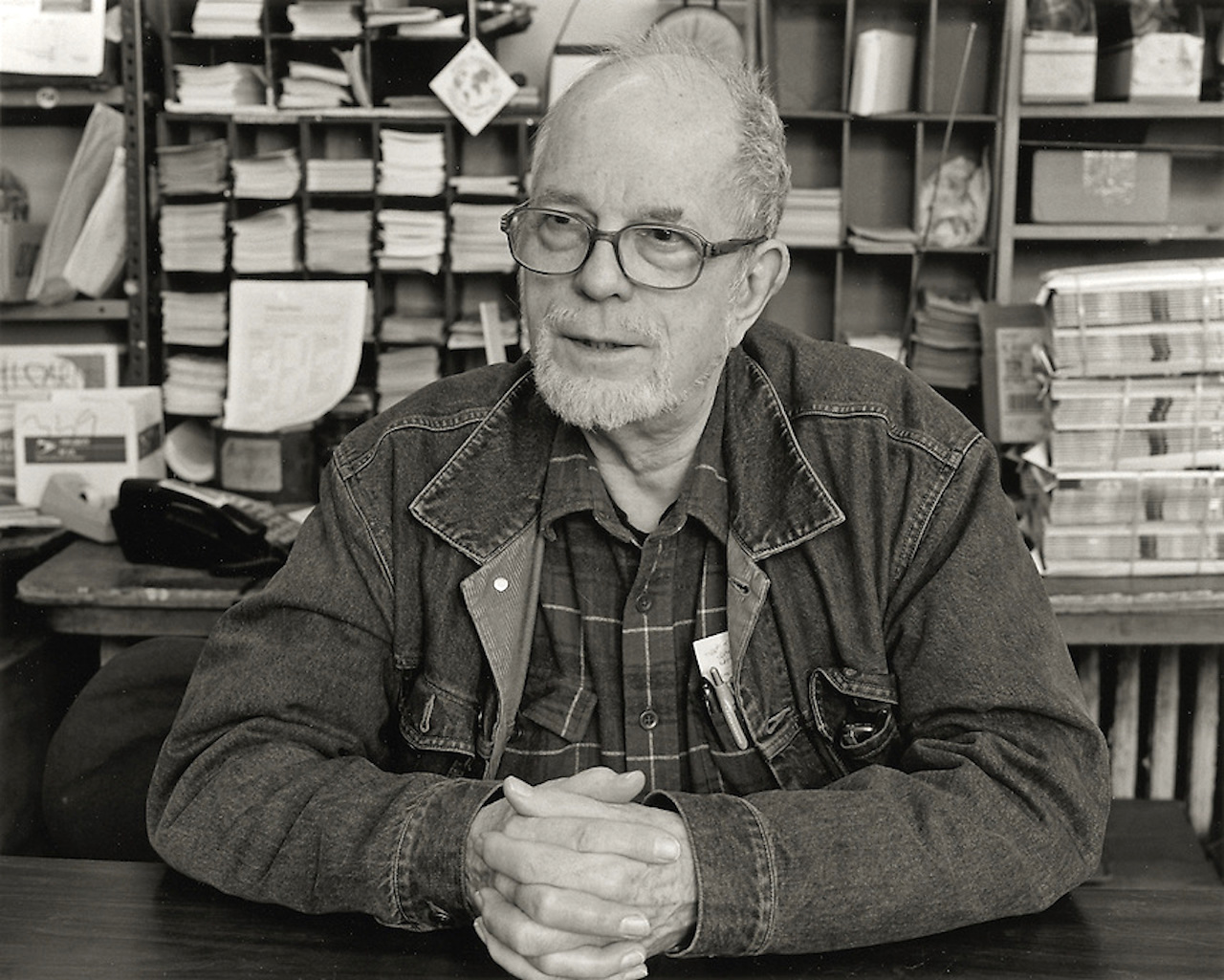

In the interest of brevity I’ve chosen to encapsulate the complex issues at stake in the history of two individuals that I happened to know personally: Dorothy Healey, for a time head of the Communist Party in L.A.; and David McReynolds, who ran for U.S. president on the ticket of the Socialist Party USA (the left wing of the old Socialist Party) in 1980 and again in 2000. My contact with Dorothy was limited to a single afternoon and a long interview I did with her when researching my biography of Paul Robeson. I knew David much longer and better. Both are deceased.

To step back for a moment, in 1981 Paul Robeson Jr. invited me to undertake his father’s biography and offered unrestricted access to the vast family archives previously closed to scholars. (It will be recalled that Paul Robeson was a concert singer and film actor who became a major activist in leftist causes in the postwar era.) Delighted at the offer, I set to work immediately, alternating archival research with intervals of travel and interviewing. Some of the people I met along the way were wonderfully open and forthcoming, while others, having had the courage to live unconventional lives, seemed retrospectively hellbent on covering their tracks. Oral history is a tricky enterprise. Interview someone on a day when their bursitis is kicking up, and memory can turn acidic; two days later, symptom-free, bitterness gives way to warmth and compassion.

Dorothy Healey: Unorthodox Communist

Of the many remarkable people I’ve met over the years, none impressed me more than Dorothy Healey, the one-time leader of the Communist Party (CP) in California. When I walked into her apartment that spring day early in 1982, she was from the outset feisty and free of affectation—far removed from the standard caricature of the rigid, dogmatic Communist, though a devoted Party member she had indeed been (until 1968). Throughout the period of her membership, the CP leadership had been overwhelmingly male, and policy decisions descended from the National Board down to the rank-and-file. Yet Dorothy had managed to rise to the head of the Party’s large L.A. branch—the Los Angeles Mirror dubbed her the city’s “No. 1 Red”—and by the late ’50s she’d been elected to the CP’s National Board.

But this should not be taken as evidence of Dorothy’s knee-jerk submission to Party dictates. She despised revolutionary bombast and rigidity and never robotically yielded to Party discipline. “We were 3,000 miles away from the God-damned National Office [in New York City],” she told me, “away from ‘Prussian Communism.’ … [W]e did have a lot of freedom of operation here in a way that nobody else had.” Given our assigned topic of “Robeson,” we began by talking about the CP’s record dating back to the 1920s, of which she felt justifiably proud, a record of fighting racism both within the CP and in the country at large. The Party had been virtually alone among political organizations in its insistence on racial integration, and Blacks had long been represented—in both the ranks and the Party leadership—in numbers proportional to their presence in the population at large. This factor had been the source of the CP’s appeal to Paul Robeson, though he never affiliated formally with the Party. When we turned to talking about the emergence of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in the 1960s, Dorothy counted herself among the few party members who greeted the New Left with enthusiasm. She urged the national CP leadership to fully embrace what she called “the most significant outbreak of youthful radicalism in thirty years.” Gus Hall, leader of the CP, saw the situation differently. He regarded SDS as at best a distraction and at worst a threat to Communist influence. He insisted, much to Dorothy’s disgust, that “no Party worker should join SDS,” which he labeled a “petty bourgeois” organization. In opposition to Hall, Dorothy led an energetic struggle in southern California to support SDS, as did the Boston CP chapter and a few others. However, when it came to the Black Panther movement, Dorothy showed only limited sympathy. While admiring its dedication, she told me that she thought the Panthers embodied “some of the worst aspects of street culture.” (It was one of the few issues during our long talk about which we disagreed.) Conversely, when Jim Jackson, an African-American second-tier Party leader, wrote a series of editorials denouncing Malcolm X, an angry Dorothy dismissed them as “vitriolic and hysterical.” She also criticized her fellow CP member Angela Davis, whose intellect she respected, for defending the Panthers, difficult though she found it “to fight with those who were near and dear to you.” After Dorothy resigned from the CP in 1968 to protest the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, she further faulted Davis for remaining in the Party (which she did until 1991). Dorothy’s view of the emerging Women’s Liberation movement in the late ’60s was basically positive, but measured. She thought the feminist critique of the CP’s “overwhelming sexism” to be exaggerated, and in defense of the Party she pointed out that as the CP had advocated 24-hour daycare centers as early as the mid-1930s. Yet she did acknowledge that, generally speaking, the Party was unquestionably male-dominated, though she felt that the leadership had historically been right to give the highest priority not to women’s rights but to strengthening trade unionism and to “the Negro question.” Acknowledging the Party’s patriarchal structure, Dorothy conceded in retrospect that she hadn’t been “very sensitive” to this issue: “1 wasn’t offended by the sexism. I considered the male comrades who indulged in that were just jackasses, more to be pitied than censured.” But she knew that some women in the Party felt otherwise, and cited Betty Gannett as one example. Gannett had never been elected to the National Board, though Dorothy thought her “brilliant” and felt certain that “she would have been [elected]if she’d been a man, no question about it.” She also acknowledged that her own demotion of the feminist issue probably did reflect to some degree the well-known “capacity of the oppressed to internalize the standards of the oppressor.” Yet she expressed dislike, too, for what she called certain “awkwardnesses” in feminism—“the overstatement, the over-rhetoricizing of positions, the posing of women’s liberation as against the general emancipation of all humanity.” Going even further, she expressed concern that some feminists were “making a political question out of sexual preferences, so that some young women have gone into lesbian relationships not because they wanted to, in the sense of physiological and biological or psychological desire, but because politically they thought this equated with emancipation, equality.” I assured her that—at least from my experience in the gay movement—if such instances existed, they were rare. She wasn’t persuaded, because apparently the homophobic stance of the Party’s national leadership had influenced her more than she was aware, or cared to admit. In fact, the official Communist take on homosexuality had a complicated history. Following the successful revolution in Russia in 1917, the Bolsheviks had abolished all legal restrictions on same-gender sexuality. But less than twenty years later, Stalin reversed that position, declaring homosexuality to be a diseased product of capitalism, and he re-criminalized it with a three- to five-year prison sentence—a more severe punishment than had existed under the czars. The American Communist Party (CPUSA) had dutifully followed suit, as did the various Trotskyist and Maoist groups. All took a dim view of homosexuality as a “character disorder.” The CPUSA was itself stiflingly puritanical. It even took a negative view of “recreational sex,” and it banned outright all applications for membership from homosexuals—a policy that in 1950 led to the resignation of Harry Hay, who would soon go on to found the pioneering homophile group, the Mattachine Society. Dorothy further revealed to me that she had been the person assigned the job of notifying certain members of the Party—including Harry Hay—that their sexuality made them personæ non grata. In retrospect, Dorothy deplored the Party’s treatment of homosexuality and expressed particular disgust over what she called CP leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn’s “blatant” homophobia. Bettina Aptheker, however, has provided a somewhat gentler view of the CP’s attitude, writing that in the Communist Party of Northern California in the late 1970s she’d found that her lesbian identity was at least “tolerated” on a kind of “Don’t ask, don’t tell” basis. However, she never doubted that the national leadership of the Party was profoundly homophobic.* Aptheker also discovered that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn had in fact lived with a “known lesbian,” Marie Equi, a physician. Flynn’s biographer, Nancy Krieger, has described their relationship as “an intense, emotionally involved” one, but concluded that it had never been sexual. Such a distinction, Aptheker believes, “belittles” the relationship (which is, given the lack of concrete evidence, a debatable judgment). Aptheker is still more certain, though no more persuasive, that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn “didn’t cast negative judgments on people’s sexual orientation.” As proof she offers the fact that in the 1920s Flynn was a member of New York City’s Heterodoxy Club, to which a number of “out” lesbians—including Amy Lowell—belonged. But it’s also possible that Flynn retained her membership in the Club despite the presence of known lesbians. We simply don’t have the needed evidence for a confident judgment. On leaving the Communist Party after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Dorothy stressed her discontent with “a distorted version of democratic centralism to compel approval of decisions made without prior discussion among the membership.” She made it clear, though, that she was not resigning in a “God that failed” state of mind; nor was she to any degree “embracing capitalism.” She had lost her party but not her political passion. She promptly allied herself with the democratic socialist New American Movement (NAM), and continued her involvement after it merged with Michael Harrington’s Democratic Socialists of America. To turn from the Communist disdain for homosexuality to the attitude of American socialists is to shift gears almost entirely. Though the U.S. was by 1950 heading into a conservative deep freeze, in California there remained a decided “edge of Bohemia” to the L.A. chapter of the Socialist Party. Membership had fallen from its high point in the 1920s and ’30s, but in stark contrast to the rigidly Marxist Left, the Socialist Party still sounded utopian echoes from the late 19th century, when such prominent radicals as Emma Goldman, Karl Kautsky, Eduard Bernstein, August Bebel, and Edward Carpenter had boldly defended homosexuality. David McReynolds’ story is a case in point. Sexually and politically active when still in high school, he joined the L.A. branch of the Socialist Party after graduating from UCLA. From the start, David told me, he “experienced little bias within the Party … except for some of those around Max Shachtman” (the dissident socialist who advocated working within the Democratic Party and ended up defending the U.S. invasion of Cuba). David’s feeling of near total acceptance within the Party may need some modification in light of historian Christopher Phelps’ recent discovery of a brief article published in The Young Socialist by a possibly pseudonymous H. L. Small in 1952.† The article called for “the freedom of the legally-of-age adult of both sexes to have sexual relations with whomever he or she wishes of the same or opposite sex, without fear of sanction.” Comments Phelps: “That The Young Socialist would publish such an article at all without disclaimer or controversy is testament to the scope of its internal freedom”—which is not to say, Phelps cautions, that either the Party or its youth branch “was free from homophobia.” Undoubtedly true, though in 1952, at the height of McCarthyism, Small’s article represents something of a miraculous oasis in a desert of belligerent bigotry. After graduating from UCLA, David moved to New York and joined the staff of the socialist-oriented War Resisters League, for which he worked for nearly forty years. At WRL, his homosexuality was never an issue—which he ascribed to the fact that the “secular pacifists” of WRL were “much more profoundly radical than … most Marxists.” Yet surely another part of the explanation is that David never became an activist on behalf of gay rights. As early as 1965, he did make an effort to connect with the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO), the tiny segment of the gay population then attempting to organize politically. In 1965, he even attended one of its conferences, but was unimpressed. He disagreed strenuously with the insistence of Frank Kameny, one of ECHO’s leading figures, that “you are not going to cure society’s prejudices by leading the homosexual into a rejection of society’s values.” Nor did David like the look of the attendees at the conference. Not only were they all white; they were also “very quiet, sedate, everyone looking terribly respectable.” They could, in his view, “have passed for some sort of Junior Chamber of Commerce types.” He came away further convinced that it was not necessary “to set up organizations of homosexuals as if they were some kind of minority that was unique.” He gave no credit to the “sedate” members of ECHO for their bravery in attending a public conference and openly calling for gay and lesbian rights, automatically opening themselves up to the threat of physical violence and loss of their jobs, their apartments, their straight friends, and their families. Four years later, when the Stonewall Riots erupted, David admitted to being stunned: “That crowd was the last crowd I would have expected to have a rebellion. God bless ’em!” Henceforth, he believed that “the openness of homosexuals is permanent”—a development he welcomed, though he continued to invest his time and energy not in achieving civil rights for gay people but in what he considered the more important, more encompassing issues related to race, class, colonialism, and war. A dedicated “peacenik” and a passionate, brilliant public speaker, David would in 1980 (and again in 2000) win the nomination of the Socialist Party USA to run for president of the United States. His campaign platform centered on the struggle for economic democracy. In personality and policy he was something of a precursor to Bernie Sanders. In fact, while campaigning in Vermont in 1980, David actually conferred with Sanders, who had not yet become mayor of Burlington, but failed to get his endorsement. In the end David only received some 10,000 votes, but he was unfazed. His commitment to socialism and to nonviolence would remain the pillars of his political world—which meant he would always live on the edge of poverty, right up until his death in 2018. During his 2000 campaign he described himself as “a badly read Marxist and a Gandhian pacifist who never found the perfect formula to blend Marx and Gandhi.” * Bettina Aptheker’s affectionate portrait of Dorothy (Intimate Politics, 2006) agrees with my own. Most of my account in this paper derives from the tape recordings that Dorothy and I made in 1982, now housed in the Martin Duberman Collection on Paul Robeson at Howard University. Also useful were Joel Gardner’s interviews with Dorothy (1972–74) at the UCLA Oral History Research Center. † The quotations that follow are from my five lengthy interviews with McReynolds in 2008. I’ve also utilized his private papers, then divided between the Swarthmore Peace Center, the War Resisters League, and his own apartment. The Christopher Phelps article, “Socialism and Sex” is in New Politics, Summer 2008.David McReynolds: Socialist Ally

Martin Duberman’s recent books includeAndrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary andHas the Gay Movement Failed?