BY LUCK OR FATE, I met and had a brief but intense love affair with one of the most important founders of the Gay Liberation movement—Carl Wittman (1943–1986). While not as well known today as Harry Hay (1912-2002) or Bayard Rustin (1910-87), Carl was a consequential early liberationist, known for his “Gay Manifesto,” his work as a cofounder of the pioneering gay magazine RFD, his shaping of a radical faerie consciousness and nature-centered spirituality, and his radically gay lifestyle. Like Henry David Thoreau or Walt Whitman, Carl Wittman was quintessentially American.

We met by looking through a small hole drilled into the metal partition between adjoining stalls in a men’s room on the U-Cal Berkeley campus in February of 1969. Within an hour we had consummated our meeting at my nearby apartment. These days a men’s restroom probably sounds like a seedy place to meet, but in 1969 it was a primary way (other than bars, which I hated) of meeting a fellow traveler. Both of us were married to women at the time, but during our three-month affair, Carl’s marriage broke up and mine came to the brink of dissolution.

Carl and I were an unlikely couple. I was already something of a contradiction, a graduate student at Berkeley studying Chinese history who came from a large and involving Italian-American family, while Carl was a “red diaper baby” who had become a national leader in New Left political groups like Students for a Democratic Society. I had gone to a few SDS-sponsored antiwar demonstrations, but I really had little understanding of Carl’s past history. By that time he had broken with his fellow SDS radicals over their homophobia. Some time after leaving SDS, Carl transferred his radical impulses to Vietnam War resistance and gay liberation. When I met him in the spring of 1969—right on the eve of Stonewall—he was just coming out, and he was writing what others have called the “bible of Gay Liberation.”

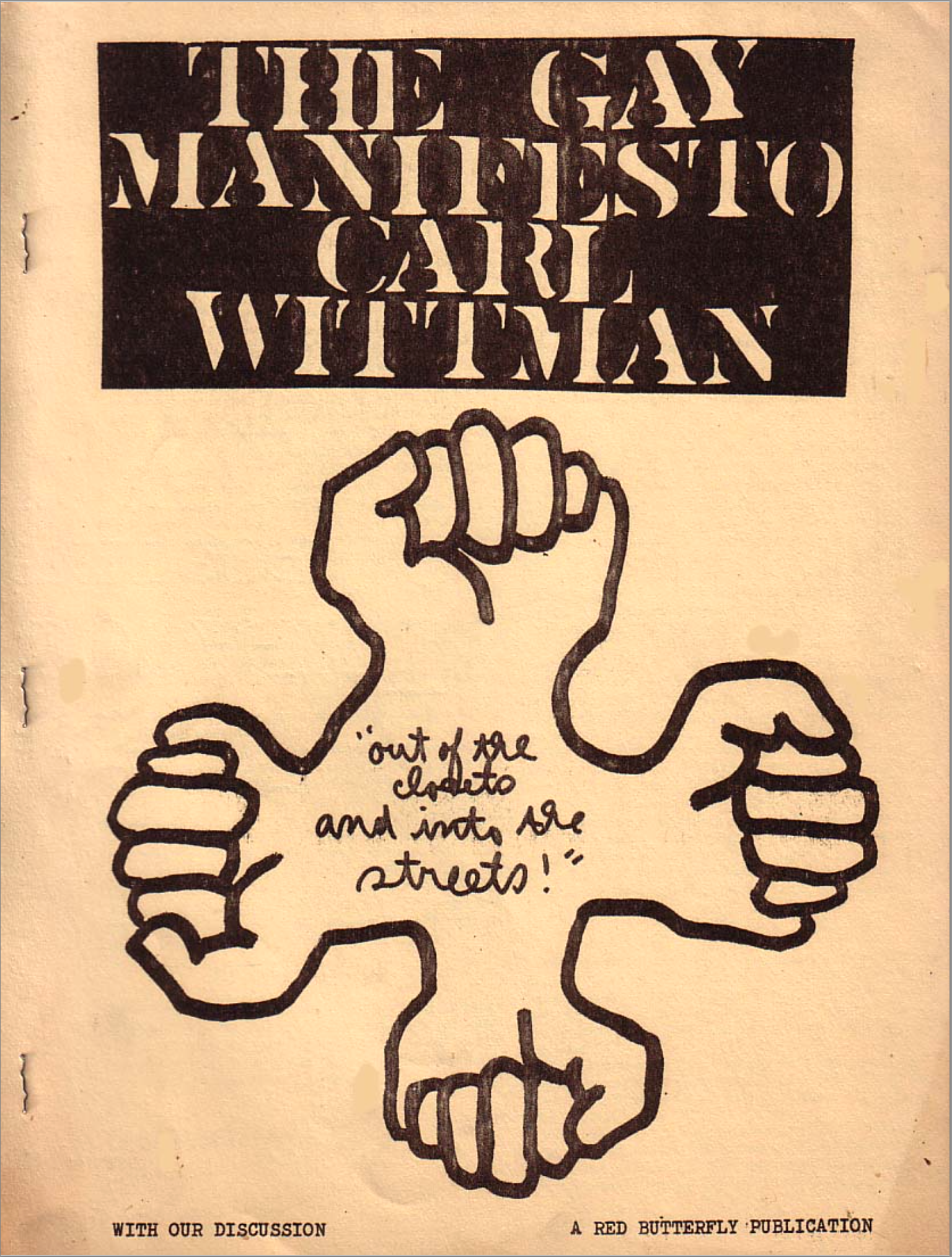

Carl’s models for the Manifesto were Marx’s Communist Manifesto and the SDS Port Huron Statement. Consequently, it was written in the style of a left-wing screed. It was a call to action directed not at those in power or at society at large but at gay people themselves, urging them to cast off their chains of mental enslavement, their shame for being queer. Everyone knows about the Stonewall Riots of June 28, 1969, but few people know that Wittman’s “Gay Manifesto” was written before the riots (though it wasn’t widely published until 1970). Today, GLBT historians either overlook Carl Wittman or they sanitize his life by omitting unsavory details such as his work as a male prostitute.

Carl was born and raised in a New York City suburb and attended an elite East Coast college, Swarthmore. His activities in SDS were focused mainly in Newark and Hoboken, New Jersey. He was also part of a group of young idealists who had gone into obscure and remote areas of the South to fight against racial segregation. After leaving SDS, he moved to San Francisco, but he left the city in 1971 because he felt it was becoming a gay ghetto, and he was opposed to all ghettos: black, Jewish, or gay. He moved to rural Oregon and, in the spirit of the times, formed a gay commune. Similar communes in remote areas like Grinnell, Iowa, Elwha, Washington, and Butterworth Farm, Massachusetts, joined together with their gay brothers in Wolf Creek, Oregon, to produce a gay-oriented, back-to-the-land magazine dedicated to serving the needs of “country faggots” and ending their isolation.

The first issue of RFD appeared in the fall of 1974, and it soon became a lifeline for those living outside of urban centers. The meaning of RFD changed with each issue, beginning with “Rustic Fairy Dreams,” followed by “Reckless Fruit Delight,” “Rabbits, Faggots and Dragonflies,” and so on. Harry Hay visited in 1975 to meet Carl, and there was some minor collaboration between them. However, while Hay is honored today for founding the Radical Faeries in 1979, Wittman is rarely mentioned in the founding of RFD five years earlier. But Hay was based in Los Angeles, one of the coastal cultural centers of the media establishment, while Wittman was based in an area as remote as Walden Pond or Camden had been for Thoreau and Whitman in their day.

In 1980, Carl moved to Durham, North Carolina, which at that time was, like Wolf Creek, Oregon, far from the centers of the gay world. He moved to be there with his lover. But Wittman had already acquired HIV and would not live much longer. Radical to the end, he committed medical suicide on January 22, 1986, one month before his 43rd birthday.

Leaving Carl in 1969 was one of the most difficult things I ever did, but my Italian family and their heritage were not something I could give up. So I chose to save my marriage with my pregnant wife. I never saw Carl again after that, but I never forgot him or stopped loving him. After my wife died in 1997 and I began to write a history of my turbulent family, I contacted over thirty of Carl’s relatives, friends, and SDS colleagues in an attempt to understand him better and how he had affected my life. I read everything I could find about Carl’s involvement with SDS, Gay Liberation, RFD, and his pioneering work in country dance, where he developed a gender-neutral system of dancer roles.

More about Carl can be found in my new book Remember This: A Family in America (Hamilton Books). Carl’s and my story together constitutes only a quarter of the 253-page memoir. Still, it is the most substantial treatment of Wittman’s life that has appeared to date. I hope it will begin to rescue Carl and his work from the oblivion into which they have fallen. He was a radical and probably would have been out of sync with today’s GLBT culture and politics. I hope I have preserved something of a life that deserves to be remembered.

D. E. Mungello is the author of the recently published Remember This: A Family in America (Hamilton Books).