FEAR of her same-sex desires stalked poet Charlotte Mew’s life and haunted her work. She feared that such desire was just another symptom of the family legacy of madness, which she feared even more. On March 24, 1928, afraid that she was succumbing to this trait, she drank Lysol from a cheap brown bottle, ending her own life in a brutally efficient way.

I’ve loved Charlotte Mew’s poetry ever since I stumbled across a copy of her first volume as a teenager. Her words spoke to me in a way I’d never experienced before. The Farmer’s Bride, her first published work, is a slim, brown volume of seventeen poems published in 1916. The title poem is a heart-wrenching verse in the voice of a farmer who loves his young wife but laments that she is unable to give herself to him either emotionally or physically. It’s easy to read in Mew’s passionate verse her own longing for the bride: “The soft young down of her, the brown,/ The brown of her—her eyes, her hair, her hair!” The farmer is both lamenting and wondering how long he can continue without raping his wife. He is helpless, he says, in the face of such beauty and desire.

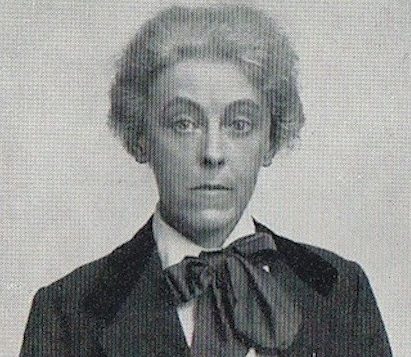

Charlotte Mew was born in London in 1869, the daughter of architect Frederick Mew and Anne Kendall. She had been aware of the need for secrecy and suppression right from the start.

Charlotte believed that insanity was hereditary, having seen the proof with her own eyes. Her close friend Alida Monroe wrote that this knowledge had the “most damaging psychological effect” on Charlotte. It led her to make a pact with her sister Anna that they would never marry or have children. Charlotte certainly felt that madness was always lurking, and she often consulted doctors to “get her nerves under control.” However, even toward the end of her life, her doctor maintained that she was not insane.

But there was another layer to Charlotte’s fear, one that she was desperately ashamed of: her desire for other women. As a schoolgirl she had experienced her first taste of physical longing when she fell in love with her headmistress Lucy Harrison. It was an experience that would leave a lasting mark upon her both physically and emotionally. When Charlotte heard that Miss Harrison was leaving, she “leapt up and in a wild state of grief began to bang her head against the wall.” Lucy had awoken in her an intense sexual attraction, and the teenage Charlotte was besotted. Fearing for his daughter’s mental health, Frederick Mew begged Miss Harrison to take Charlotte with her when she left and to take a position as a tutor with a boarding house. This reaction cemented in Charlotte’s mind the link between her sexual desires and “madness.” From this point on, she was aware of the need to suppress her same-sex feelings or risk losing her sanity.

Lucy agreed to take her, and for the next two years Charlotte learned and worked away from her family. All this came to an end though when Lucy Harrison herself fell in love with one Amy Greener, another teacher, and they moved north to live and work together. For Charlotte this was a devastating blow, and she expressed her grief in an early sonnet in which she recognized that for years she had stood and “beat my heart against the door.” She also recognized that her desire was something more than the usual teenage confusion. It both terrified and excited her, and it also set the pattern for all of her future relationships: Charlotte would never be attracted to a man, but she would always choose women who were not available. Her love for women was destined to be both unrequited and even mocked.

Charlotte Mew lived in the era of Oscar Wilde, and, like Wilde, she converted her torment into works of art. Unlike Wilde, she was determined to conceal her true nature. Forced by circumstance to take a job, she nevertheless clung, like all of the Mew women, to her status of shabby respectability in the world of middle-class London, where lesbianism was nowhere to be found. Despite her best efforts, however, her work remains highly relevant to feminist poetics in the way that it addresses issues of sexuality and identity. Her work cleverly negotiates the issues of feminine identity in the early 20th century, the visibility of the feminine in poetry, and the meaning of sexuality and desire.

We see this clearly in one of her later poems, “Madeleine in Church,” in which she further explores the tensions between her religious faith and her lesbian inclinations. Madeleine is the embodiment of a woman who is filled with sin yet seeks redemption. Madeleine is possibly used by Mew to express her longing for redemption despite her inability to overcome her sinful sexual nature. Throughout her poetry Mew uses the color red to symbolize extreme feelings and sensual experiences, and Madeline confesses that she cannot sit and look at “red carnations burning in the sun,/ Without paying so heavily for it.”

When it was published, The Farmer’s Bride was very well received, and to Charlotte’s surprise she found herself quite famous. Thomas Hardy was an admirer, as were Siegfried Sassoon and Virginia Woolf. However, she was not able to capitalize on this success, and her fame soon faded. Part of this is due to Charlotte’s reluctance to step out into the public eye. She feared until her death exposure of both her true sexual nature and her familial insanity. Thus she chose to live quietly and published very little. Her name quickly fell out of the public consciousness, while her suicide only reinforced her image as a Victorian eccentric.

Luckily for us, Mew was not entirely forgotten, and we are able to revisit her work, which gives us a tantalizing glimpse into the construction of both lesbianism and madness in the early 20th century. “We are what we are,” Mew wrote in one of her letters, “the spirit afterwards, but first the touch.”

Rebecca Batley, a historian and writer, has a particular interest in the art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.