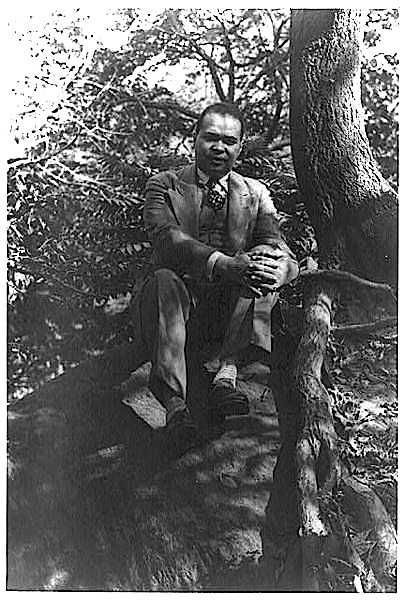

And Bid Him Sing: A Biography of Countée Cullen

And Bid Him Sing: A Biography of Countée Cullen

by Charles Molesworth

University of Chicago Press

304 pages, $30.

THE EARLY LIFE of the first published poet of the Harlem Renaissance is wreathed in mystery. Probably born in 1903, in Louisville, Kentucky—or perhaps in New York City, or, as some have maintained, Baltimore—Countee LeRoy Porter was the child of a single mother. He spent his early years in poverty with his grandmother, and perhaps his grandfather, in Harlem. In his early teens he was adopted—perhaps informally, perhaps legally—by a popular and highly respected Harlem minister, Reverend Dr. Frederick Cullen, and his wife, after which Countee L. Porter became Countée Cullen. Thereafter, he always styled his first name with the accent, and he nicknamed himself “Tay.”