Manly Love: Romantic Friendship in American Fiction

Manly Love: Romantic Friendship in American Fiction

by Axel Nissen

University of Chicago Press

231 pages, $45.

Once upon a time, American men could openly express intense love for each other without shame or self-consciousness, without any sense of being effeminate or unnatural. Such “manly love” did not preclude emotional, sexual, or conjugal relationships with women. This is Axel Nissen’s argument in Manly Love: Romantic Friendship in American Fiction.

Nissen’s study is historical as well as literary. The main sources of information about the love lives of people in the past—court records, medical texts, diaries, and letters—have their limitations. Nissen contends: “If we want to understand what it was like to be a man-loving man in the nineteenth century, we should turn to the fiction of the period.” Fiction was where Victorians explored the questions of love and (up to a point) sexuality. Nissen treats male romantic friendship as his central paradigm, “a pervasive cultural myth” that informs the lives, hopes, and ideals of 19th-century American men.

Although “Victorianism” usually means repression of sexuality in general, and homoeroticism in particular, Nissen found that “expressions of men’s love for each other were all over the place in Victorian America.” The works that Nissen reviews were by no means underground or peripheral: they were published openly by prestigious publishers, and some went through several editions. Some of the authors were scions of New England Brahmin families, whose voices represented “the ruling literary and cultural elite.” To be sure, there were constraints: an unspoken sexuality might be hinted at but was not to be expressed overtly. Nissen devotes full chapters to five works: Cecil Dreeme, by Theodore Winthrop; Roderick Hudson, by Henry James; A Saloonkeeper’s Daughter (about female romantic friendship), by Drude Krog Janson; Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain; and A Hazard of New Fortunes, by William Dean Howells. In the two introductory chapters, he discusses other works, including novels by Bayard Taylor and short stories by Bret Harte, whose biography Nissen has written (Bret Harte: Prince and Pauper, 2000). Bret Harte is renowned as a chronicler of the California gold rush.Many of his stories deal with male love—usually, but not always, with tragic endings. Two of them—“Tennessee’s Partner” and “In the Tules”—are in Nissen’s earlier book, Romantic Friendship Reader: Love Stories Between Men in Victorian America (2003). In the California of 1850, when women were only one-twelfth of the population, men turned to each other for friendship and love. Many of the young men who flocked to California were well-educated and came from good families—not the grizzled types featured in Hollywood movies. Casual nudity was often observed. The description below is by Dan De Quille, fellow journalist, roommate, and bedfellow (only one bed) of Mark Twain: Men meet us and pass us, all going about their business as on the surface, and frequently a turn brings us in sight of whole groups of them. We seem to have been suddenly brought face to face with a new and strange race of men. All are naked to the waist, and many from the middle of their thighs to their feet. Superb muscular forms are seen on all sides and in all attitudes, gleaming white as marble in the light of many candles. We everywhere see men who would delight the eye of the sculptor. (Quoted in “Rewriting the Gold Rush: Twain, Harte and Homosociality,” by Peter Stoneley, Journal of American Studies, August 1996). It would seem that these young men developed their bodies, and exhibited them to best advantage, for the sake of other men. Joseph and His Friend (1870), by Bayard Taylor, is considered the first gay American novel. The copy I received from the Boston Athenaeum’s off-site storage was held together by a ribbon; the covers were detached, though the paper was still good. A browned and crumbling slip informed me that I was the first person in over a century to check it out.With the moldiest of expectations, I started reading, and before I knew it, I was totally engrossed. Taken on its own terms, it’s a fine novel—the story of Joseph, a prosperous, handsome, naïve young farmer in rural Pennsylvania who marries a deceitful woman and then, through a train accident, meets Philip, a man slightly older than himself, who will be his friend, mentor, and true love. Joseph and Philip intelligently discuss their love, their circumstances, and their obligations to others. After various tribulations, a happy ending of sorts is achieved: Joseph’s unworthy wife commits suicide, and Joseph will marry Philip’s sister and live together with her and Philip. Perhaps Philip will find a woman of his own, perhaps not. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is our Great American Novel—an adventure story, a satire, a comedy, and much more. With thousands of essays written on it, does Nissen have anything to add? He does: “In this chapter I will place Twain’s classic novel in two nineteenth-century discursive contexts that have been obscured in the existing criticism: the fiction of romantic friendship and the public debate on the homeless man.” As most readers know, Huck is a boy of about fourteen who is in flight from a violently abusive alcoholic father. His main friendship bond is with Jim, a runaway slave. Nissen refers to Jim as “an African American, middle-aged male”—but Jim’s age is never given explicitly. Jim refers to himself as “ole Jim” and Huck calls him “old Jim,” but these are expressions of familiarity, not statements of age. Illustrators and readers over the last century have imagined Jim’s age at anywhere from his teens to about forty. I personally see him as six feet tall (specified in book), athletic, and about 23. In addition to Jim, Huck also bonds with Tom Sawyer and briefly with Buck Grangerford, who is killed in a feud. Besides Huck and Jim, the other male couple is a pair of tramps or hobos known as “the duke” and “the dauphin.” All four are fugitives; all are outcasts. Nissen’s originality and critical acumen come through strongly in his analysis of the Dauphin-Duke couple, who in their affectations, manipulations, and general humbug parody certain types of gay men. Friendship is put into the crucible in the chapter, “You can’t pray a lie.” Huck has written a letter to old Miss Watson, telling her that Jim, her runaway slave, has been captured and is being held for her. Huck is in a terrible moral dilemma, torn between the claims of friendship and the claims of law, custom, and religion. If he remains silent, he will be guilty of stealing the property of a poor old woman and will go to hell for this sin. On the other hand, Huck remembers how good Jim was to him on their trip down the river. Twain builds the tension to an almost unbearable pitch until Huck makes his decision—with a single sentence, a sentence like a thunderbolt. The sentence is like the keystone of an arch: everything in the novel leads up to it, and everything follows from it. Huck says to himself: “All right, then, I’ll go to hell”—and tears up the letter. Friendship has triumphed. The next step is to liberate Jim, and his old friend Tom Sawyer will help him do this. Nissen regards Cecil Dreeme, by Theodore Winthrop—who came from one of the most illustrious families in New England—as the “ultimate fiction of romantic friendship.” The novel is interesting in many ways, not least the convoluted sexual psychology of Robert Byng, the narrator. It went through nineteen printings during its first five years in print, perhaps owing its acceptability to a cop-out ending, in which the beloved male, Cecil Dreeme, turns out to be a woman in drag, and Densdreth, the glamorous villain who represents homoerotic temptation, turns out to be totally heterosexual. How to end a story of romantic male friendship is a cultural as well as artistic problem. Of the 21 works Nissen discusses, six (29 percent) end in death (for one or both partners), six (29 percent) end in marriage, and three (14 percent) end in both death and marriage. Only six (29 percent) end otherwise. In some cases one partner ends up marrying a female relative of his beloved friend. Manly Love is a pleasure to read, full of insights that go beyond the analyses of individual works. For example, Nissen makes a convincing case that our era’s emphasis on genital sex has obscured the aspects of love and friendship in relationships. In a several-page digression on “the beauty of men” he comments on the role that physical beauty has to play in romantic friendship. At the same time he makes a distinction: “One of the losses of our current outlook is the ability to separate aesthetic appreciation of beauty—be it male or female—from sexual attraction.” Nissen adds that practically all of the male authors treated in his study were handsome men. Axel Nissen is professor of American Literature at the University of Oslo. His book drives home the point that love and friendship between males, with or without sex, is a crucial component of the human experience. John Lauritsen, whose latest book is The Man Who Wrote Frankenstein

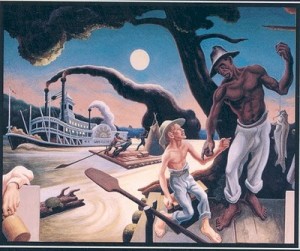

A Social History of the State of Missouri (detail of north wall), 1936. (2007), maintains a website at paganpressbooks.com/jpl.