Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit

Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit

by Paul Martineau

Getty Publications

200 pages, $39.95

THE HUMAN NAVEL has historically symbolized the evolutionary past, through millennia cross-culturally, and for all ethnicities. The navel represents the universal maternal connection embodied in 6th-century Persian silver shallow drinking bowls with a bulbous bellybutton indentation; in a rosette of lotus petals radiating from the Hindu god Vishnu’s navel; or, in Greek mythology, in the conical-stone omphalos (the Greek word for navel) at the Sanctuary of Apollo on Mount Parnassus, designating the earth’s center. The navel also symbolizes the unknown and mysterious. When Freud conceded that not all dreams were interpretable—some contained an inextricable knot—he labeled this predicament a “navel.” The Belly-Button Biodiversity Project studies the navel as the gateway for a microbial ecosystem: for years the bellybuttons of hundreds of participants have been cotton-swabbed so the bacteria found there can be analyzed. Surprisingly, many specimens have revealed microorganisms found only in marine environments or in foreign soils. The navel can arouse pleasurable unpredictability. Madonna, whose navel is pierced with a gold ring from which dangles a diamond horseshoe charm, exclaimed: “When I stick my finger in my belly button, I feel a nerve in the center of my body shoot up my spine.”

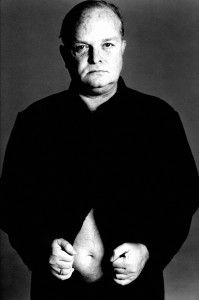

Whether exposed and erotic or concealed and mysterious, navels generate attention. Of course, obsessive preoccupation with the navel can be classified negatively as fetishistic, as a personality disorder known as omphaloskepsis, which is narcissistic navel-gazing. The navel has been an element within many photographic images. Critic A. O. Scott observed that photographers such as Richard Avedon extended their omphalic inquisitiveness to making portraits that featured bellybuttons, from one of Truman Capote’s navel peeping through a dark shirt, “a winking eye in an expanse of pale flesh,” to the exposed midriffs of the Fugs, a 1960s band, to truck-stop waitresses, rodeo cowboys, and drifters.

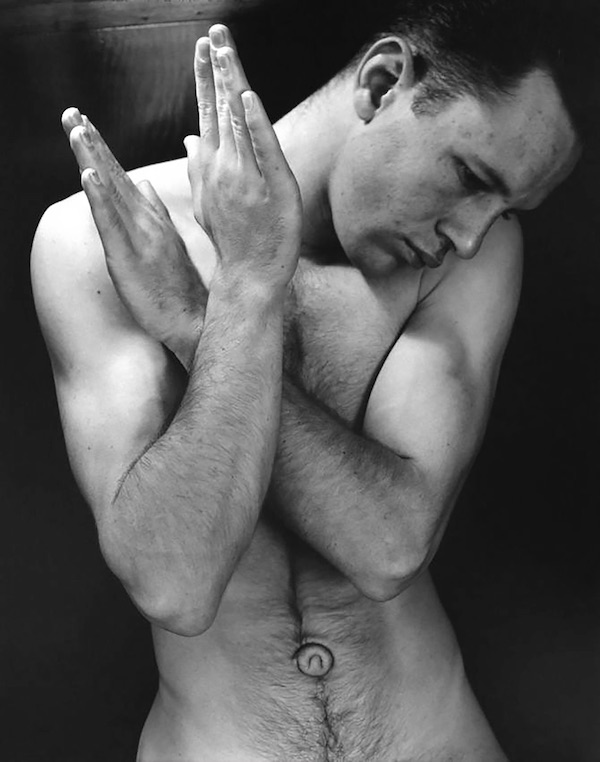

In Minor White’s 1948 nude photograph of William Smith, the focal point of the portrait is its distinctive navel, which is contoured like a tortellini. Smith’s navel seems like a relief carved in stone upon the landscape of a body. The photograph resonates with the specificity of other 20th-century homoerotic artworks. The portrait is a prototype that anticipates the sexual-outlaw erotic imagery of later gay photographers such as Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe.

Minor White (1908-1976) was renowned as one of the masters of American photography, having worked with Bernice Abbott, Ansel Adams, Paul Strand, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Weston. Like them, White was determined to legitimatize photography as an art form. He cofounded Aperture magazine in 1952, which was one of the most influential forums for contemporary art photography, and he served as its editor for 23 years. He was a curator at George Eastman House, the world’s oldest photography museum; taught at the California School of Fine Arts and both the Massachusetts and Rochester Institutes of Technology; and was a photographer for the federal New Deal agency known as the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

White encountered and resisted heterosexist institutional censorship and exclusion throughout his entire career, beginning in 1947 with Amputations, his first sequence of photographs, which was scheduled for exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. The photographic sequences had nude photographs of Tom Murphy and some shirtless images of U.S. Army buddies with whom he served, and it incorporated poetry alongside the images in a way similar to photographer Duane Michals, who also documented homosexual identities with captions. The exhibition was canceled on the pretext that the poetry wasn’t sufficiently patriotic.

During the 1970s, the feminist art movement came into existence in reaction to similar widespread gallery and institutional ostracism, and LGBT artists are indebted to them. Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party was labeled obscene by the U.S. Congress, which threatened to withdraw public funding from all institutions that showed it, and the work was banished into storage for nearly thirty years. The exclusion of gay and lesbian artwork is persistent throughout this period, from the attempts to censor Robert Mapplethorpe from the 1980s through the 1990s into the 21st century with the removal of David Wojnarowicz’ “A Fire in My Belly” video from the groundbreaking exhibit Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture at the National Portrait Gallery in late 2010. In 2015, the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art mounted Irreverent: A Celebration of Censorship, an exhibition that documented decades of intentional exclusion, acts of violence, and vandalism against gay-inflected artwork.

When Paul Martineau curated Minor White: Manifestations of the Sprit at the J. Paul Getty Museum and edited its accompanying catalog, he included a series of 32 gelatin-silver prints from a maquette titled “The Temptation of St. Anthony as Mirrors.” Martineau called it a “visual love poem.” The images were portraits of Tom Murphy. Some have him clothed in various environments, situated on coastal rock formations, rooted in woodland vegetation. Some are full-frontal nudes referenced against driftwood, roses, or leaves, others quasi-anatomical studies of body parts—hands, feet, buttocks, and of course, bellybuttons. The sequence was never before shown or published in its entirety, as White made only two copies of the album, one for Murphy and one for himself. His copy is housed at the Minor White Archives at the Princeton University Art Museum.

In 1989, thirteen years after Minor White died, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) held a retrospective titled Minor White: The Eye That Shapes. Ingrid Sischy wrote in The New Yorker that White had two bodies of work: one private and hidden from public view, the other intended for public exhibition. And yet, his same-sex sexual orientation is watermarked into nearly all of his images. In a New York Times review, Andy Grundberg acknowledged White’s “lifelong interest in the male subject, and in homoerotic imagery in particular,” observing a 1975 portrait of a young man with shoulder-length hair at the exhibition. No less an authority than Peter Bunnell, author of the exhibition monograph, MoMA’s former photography curator, and the person responsible for White’s archive at Princeton University, opined that “White’s sexuality underlies the whole of the autobiographical statement contained in his work.” In a 2008 essay, “Cruising and Transcendence in the Photographs of Minor White,” Kevin Moore asserted that White “queered” documentary photography by staging “the breakdown of a heroic modernist tradition.” White accomplished this by making images of men posing in the nude, whether contemplative or directly gazing into the lens, or as a flâneur emerging from the shadows of a city street or peering out from a half-hidden doorway in a provocative stance.

Rather than retreating into abstraction, White recontextualized the ideals of so-called “straight” or “pure” photography, which emphasizes the ability of photography to capture the world in sharp focus, as distinct from Pictorialism, which is a painterly rendering using soft focus, dreamy effects, and the manipulation of surfaces. He achieved this through an encryption of sexual orientation into most of his photographs. Of photographing a bowl that shattered on a kitchen floor he wrote: “The splinter of china was more loving than the bowl had been, as if in this form all the love of the craftsman had crystalized … turned into the symbol of the female principle, and then into the thumb print of a goddess. … I need only enough technique to remember to use my camera without bungling when I am transfixed by light.” The symbolism of the bowl or omphalos is essential to White’s personal iconography. In his photograph of William Smith, with whom he had a love relationship for more than three decades, Smith’s slender hands gracefully offer a bowl that contains only light, the fundamental element that determines what is recorded on film. (See Rochester, New York at left.)

Ansel Adams noted in An Autobiography (1985) that White was more interested than he was in the subjective meaning(s) of photographs: “It was always the inner message of the photograph that most concerned him; he always wanted to know the thoughts, feelings, and reactions of the artist to the subject and his image.” As a proponent of “equivalence”—a theory of photography in which colors, shapes, and lines reflect the artist’s inner experience or emotive state—White felt that photographs were retained in consciousness, left behind as if memorized, as mental afterimages even when out of sight.

White also came to be known for his mystical approach to photography, and he incorporated the principles of Zen into his contemplative photographs and teaching workshops. In The Zen of Creativity (2004), John Daido Loori described an experience as a student in one of White’s workshops. During an exercise, White enigmatically instructed his students to “photograph who you really are. Go deeply into the core of your being and photograph your essence.” White himself did just that—in a photograph of a metal ornament that belongs to a 1959 sequence—after spending several months intensively meditating on the meaning of a koan, a philosophical paradox in the form of a question used in Zen Buddhism. White found the answer to the koan, “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” in the form of this metal ornament. “After several months of intensive work on this koan, I saw rather than heard any sound.” And he photographed it (see image at left), after reaching the center point, recalling an afterimage, rendering its representation, and documenting his consciousness of the object. The ornament in which he could see sound was a metaphoric representation of Tom Murphy’s navel.

It is an extraordinary arc of history to see Aperture devote an entire issue, titled “Queer,” to LGBT photography. It’s a magazine that Minor White founded more than six decades ago at a time when gay people were subjected to intense criminalization, incarceration, institutionalization, and marginalization. Some have claimed that White was closeted and that he ascended into abstraction to avoid homophobia, as if the closet door could be slammed shut once it had been opened. The body of his work reflects something quite different—images that evoke homoerotic possibilities and that counter patriarchal representations of masculinity and male beauty.

Steven F. Dansky, an activist, writer, and photographer for fifty years, is the founder of Outspoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers.