A PAIR of itinerant fishermen on a makeshift raft snag what looks like a drowned man floating face-down in the Bay of Havana. As they unhook the rotting corpse, their quarry rears up to take a bite out of one of the fishermen. The friends harpoon the cadaver and paddle to the waterfront, swearing not to tell anyone about their shared hallucination. But animated corpses soon are shambling through Havana’s streets, feasting on human flesh and terrorizing the population. Our fishermen learn what has happened when they tune into CubaVision Internacional, the government-run television news network, and the anchorman announces that “Several disturbances of social order have been caused by some dissident groups paid by the U.S. government!”

The 2009 mock-horror film, Juan of the Dead, is not the blatant rip-off of the UK production Shawn of the Dead that the title implies, and displays rich Cuban humor, wryly handled by director Alejandro Brugues. Cubans are very careful not to criticize their government overtly. But satire is rampant, and the film lampoons the government’s reflexive scapegoating of the U.S. government in every crisis.

Depending on the propaganda to which one subscribes, this Communist island nation is either a haven for gay people or a trap for them. In the words of Steve Williamson of the Cuba Solidarity Campaign, Cuba is either “by far the most progressive country in Latin America as regards gay rights … or a corrupt Stalinist police state—a gulag for homosexuals, intellectuals and artists.” Whichever is true, I have long believed that GLBT Americans have an interest in knowing about gay Cubans’ struggles, supporting their liberation, and learning from their experience. When I had an opportunity to visit Cuba on a two-week photography mission in the fall of 2013, I was determined to discover which of the two conflicting images of Cuba was more accurate.*

Before leaving the U.S., I conducted some historical research to help me ask the right questions about Cuba. I was able to establish to my satisfaction the following facts that may or may not be widely acknowledged in the U.S.:

§ Cubans receive sex education from the first grade, and this education includes the depiction of gayness as an innate, immutable, and morally neutral characteristic. In 1986, Cuba’s National Commission on Sex Education introduced a program on homosexuality and bisexuality as healthy and positive expressions of sexuality. Young people I met, who have grown up with this perspective, assume that similar education takes place in the U.S.

§ The Cuban government provides free treatment to people with AIDS, and continues to pay their salaries when they cannot work. The World Health Organization confirms that Cuba’s HIV infection rate of 0.1 percent is roughly one-sixth the rate of the United States. Detractors don’t argue with the WHO’s statistics, but many take issue with the draconian measures that included, until 1993, forced quarantine of HIV-positive Cubans.

§ Openly gay people serve in public office and hold positions of responsibility in government, culture, and the arts. Since 1975, the government’s official policy against discrimination has extended to sexual orientation.

§ Mariela Castro Espín, daughter of current President Raúl and niece of Fidel, deserves much of the credit for this progress. As the Director of the Cuban National Center for Sex Education (cenesex), she has overseen the transformation of public policy at a very personal level.

§ Despite these advances, gay Cubans remain subject to the personal discrimination inherent in any macho culture. As in certain parts of the United States, many gay Cubans maintain complex closets: close friends and family may know that someone is gay, while colleagues may not.

§ Many people I met are very open about being gay, but they’re extremely cautious when discussing Cuba’s many problems, and they avoid criticizing the government.

The Visit and the Artists

My examination turned out not to be the simple project I had hoped for. Once in Cuba, I obtained a press license and interviewed a number of people, many of them gay and straight artists and musicians who were born after the Communist Revolution of 1959, and some who were already in their twenties and thirties by that time. I returned home humbled by the complexity of the situation, determined to continue learning all I could and to visit Cuba again, unburdened by such naïveté.

I was scheduled to appear on October 29th at the Cuban government’s International Press Center in Havana for my press-license screening, which I needed in order to conduct interviews with Cuban citizens. On that day the United Nations General Assembly voted, for the 22nd consecutive year, to condemn the U.S. embargo of Cuba as an inhumane violation of international law. The official I was to see at the International Press Center, a woman named Libertad, was unavailable. When I appeared on the following day, she apologized, explaining that she and her staff had spent the day managing the fallout from the balloting. Although symbolic, the vote generates extreme worldwide reactions every year. This time, a record 188 countries voted to condemn the embargo. Only the U.S. and Israel voted against the resolution.

Once I had my press license, I was able to interview the person whose work had first attracted me to Cuba, because nothing he has produced looks like what I expected from a nation of repressed artists. Alejandro A. Calzada Miranda is a 41-year-old photographer who has traveled in Europe, Russia, and the U.S. for exhibitions of his work. We met in my Havana hotel lobby and discussed how to exchange photographs. When I suggested we go to my room in order to download images to our respective computers, he said, with a tone of indulgent surprise at my ignorance, “The hotel will not allow a Cuban to go to your room.” Knowing of his reputation, and the relative freedom he has exercised, I protested that we were working on a professional project. “This is Cuba,” he said in a flat tone, and his wry smile told me far more than his words. Determined to explore the issue, I appealed to the desk clerk, who called a security guard, who summoned the hotel manager—who, after examining my press license, agreed to allow a ten-minute visit in my room but required Mr. Calzada to leave his university faculty card with the guard.

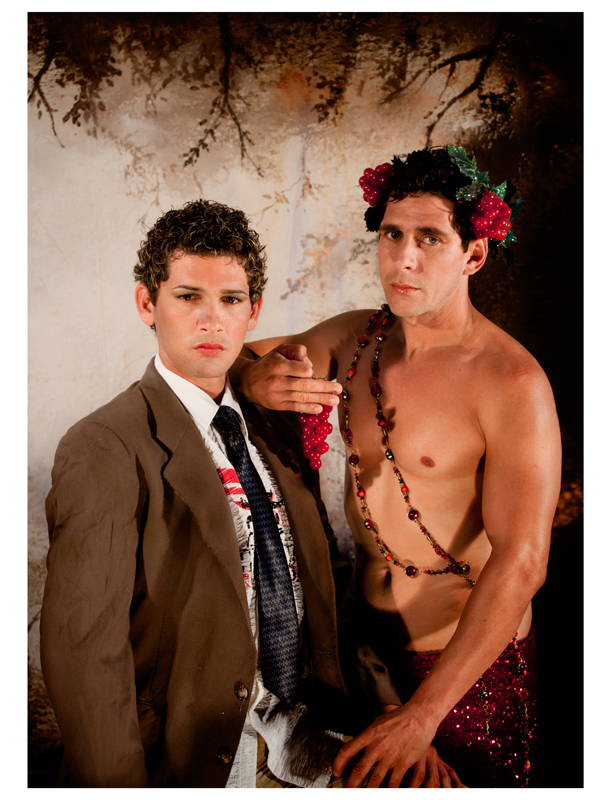

Calzada, in addition to teaching photography at the University in Havana, designs floats and costumes for the annual Parranda festival in his home village of Remedios. Some of his photographs are reminiscent of Pierre et Gilles—sexually vivacious, gender-bending, and whimsical. In a country that does not celebrate Christmas, Parranda is the place to be on December 24th and 25th. I was lucky enough to return in time for some of the preparations.

Architect Miguel Coyula, who described himself to our group as one of many “battered Cuban optimists,” explains that Cuba faces a serious population decline and brain drain. Young, educated Cubans are leaving Cuba for better opportunities elsewhere in Latin America and in Spain. Couples inside Cuba tend to practice their own version of China’s one-child policy.

Mr. Coyula recommended a 2011 film called Habanastation, which presents the problem of income disparity between two school children. As he talked, the members of our group looked at one another with puzzled faces. Finally, one of us spoke up, pointing out that Mr. Coyula had been a young boy when the revolution of 1959 occurred, and has spent his life committed to the egalitarian principles of socialism. We, eight U.S. citizens and a Canadian, have spent our lives taking for granted that some schoolchildren always will have less than others, and that some will have far more—more food, nicer clothes, better educational opportunities. This fact-of-life disparity under capitalism worries this thoughtful architect, who hopes to see the next generation of Cubans forge an economic model that incorporates planning and flexibility, more like the “sustainable Scandinavian model” and less like the “brutal Chinese model.”

Cuba’s highways are free of commercial billboards, and its newspapers and magazines are without advertising of any kind. However, in conspicuous places near airports, one sees signs of billboard-like proportions announcing “Socialismo: Más Para Todos,” “Socialism: More For Everyone.” Fidel is widely quoted as saying, “There is no civilization without the arts,” and cynics retort that the Cuban government uses its artists as tools of propaganda. Cuban dancers, musicians, painters, photographers, and other artists have freedom to travel internationally and present Cuba’s best face to the world. In the 2006 interview that his niece Mariela refers to as his “apology” to Cuban gays, Fidel pointed out the “contributions of great homosexual artists.”

Cuba’s internationally renowned Escuela Nacional Cubana de Ballet is the largest ballet school in the world, with 3,000 students, and it’s the feeder academy for Alicia Alonso’s Ballet Nacional, an acclaimed company that has performed in 58 countries and received hundreds of international awards while developing a uniquely Cuban form of ballet. Even here, however, the reciprocal propaganda machines are busy. Cuban ballet dancers are among the best-paid in the world, point out the nation’s loyalists. Yet, to counter the anti-Castro forces, the Cuban-trained dancers who appear as marquee names in top ballet companies throughout the world have achieved their international stardom only by defecting.

Defection has for 54 years been the only means for Cuban artists and athletes to work outside of Cuba. However, under an order that the Cuban government issued in September of 2013, athletes are newly able to sign contracts with foreign leagues. Within three weeks of the order, first baseman José Abreau signed a $68 million, six-year contract with the Chicago White Sox. The order represents a sea change in Cuban policy—an acknowledgment that professional sports are not, after all, counter to socialist ideals. For Cubans who truly believe in la revolución and have grown up embracing the equality inherent in a universal twenty-dollar monthly wage, the new rules will present a challenge.

A Tortured Path to Gay Equality

In the years after the Communist Revolution, the regime dealt with young gay men in differing and contradictory ways. Depending on who you talk to, gay people were either punished through imprisonment in brutal labor camps or given work assignments in lieu of military service, a humane means to protect them from endemic macho discrimination.

The most high-profile gay Cuban’s story widely distributed in the U.S., Before Night Falls (1992), by poet and memoirist Reinaldo Arenas, was subjected to the first of these two approaches. Arenas was imprisoned for two years in the notorious El Morro prison, formerly a Spanish colonial fortress and now a cultural center. Before Night Falls has been widely accepted as an accurate account of the oppression suffered by a gay artist, though some have attributed his extreme account to dementia brought on by AIDS, which he purportedly contracted upon arriving in New York. Both positions are put forth credibly by intellectuals who represent themselves as experts on Arenas. Like so much I encountered in Cuba, this story has at least two sides, neither of which is readily susceptible to verification.

In a 2006 interview, Fidel Castro claimed that he had never harbored prejudice against gays but explained that, during the early years of the revolution, he encountered strong opposition to drafting homosexuals into the country’s mandatory military service. (He blamed historical macho attitudes on the Spanish colonialists and even on the Moorish occupation of Spain.) In the face of this opposition, the government assigned gay men to the same work groups to which conscientious objectors were assigned—the Military Units to Support Production (UMAP). The statement was hailed by Castro’s niece Mariela and other supporters as an “apology.”

Mariela Castro, in most matters an apologist for the regime launched by her uncle Fidel and carried on by her father Raúl, is the inspiration behind a recent gay rights campaign. In 2009, she launched El Día Mundial Contra la Homophobia, the World Day Against Homophobia, to give GLBT Cubans a political voice. Originally a forum of academic and political panel discussions, within two years the Día added the word Gala to its name and incorporated musical performances. By its fifth anniversary, in May 2013, the event had grown into a celebration of a new openness, a feathered and bejeweled music, arts, and cultural festival that attracts gay people from around the world—but not from the entire world. U.S. citizens and legal residents are forbidden to travel to Cuba except under narrowly defined circumstances, which do not include attending Cuba’s equivalent of Gay Pride.

The U.S. embargo on trade with Cuba is now some fifty years old, and the Communist regime that it was set up to punish remains in control. Critics of the policy point to China’s dismal record on human rights and to the hypocrisy of a U.S. policy that embraces China as a “most favored nation” trading partner. They call the embargo “el bloqueo,” “the blockade,” and consider it the inhumane work of a powerful Miami-based lobby of Cuban exiles and their descendants. GLBT activists argue that the policy punishes gay people disproportionately because the blockade limits the availability of medicines needed by people with AIDS. Under the embargo, even U.S. citizens with legitimate visas for Cuban travel are subject to a $300 fine for trying to bring in cigars, rum, or coffee—Cuba’s three principal exports.

The word “blockade” might conjure an armed U.S. flotilla blocking access to Cuban ports. But we need no armed flotilla. Under Department of Treasury regulations, any ship that lands in a U.S. port, even to refuel, is subject to a million-dollar fine if it has docked in Cuba to deliver or take on cargo over the previous six months. The individuals involved are liable for up to ten years in prison. Because European ships need to refuel in the U.S., they are effectively barred from transporting Cuban goods. Thus Cuba can engage in large-scale commerce only with Latin American countries, which have their own supplies of rum, coffee, and tobacco products.

The People You Meet

Outside Havana, in the mountain town of Viñales, I met a small group of musicians from the city of Pinar del Río. Carlos, an accomplished violinist with strong African features, told me that in the fifth grade his best friend Filip asked him, “Do you like boys in the way I like girls?”

“I did not hesitate to tell him, ‘Yes,’” Carlos explains shyly, while Filip smiles at his side. “And his response made me cry: ‘No one will hurt you because I am your friend.’”

Filip, who is light-skinned and wears a Che Guevara-style beard, interrupts to tell me, “¡Carlos no era un marica!”—“Carlos was not a sissy! But he was more gentle than most boys, and he regarded girls with respect, like friends. That is why I guessed.”

The boys studied music at the University of Havana, and after graduation they returned to their home village to teach high school. Fourteen years after Carlos’ revelation, they travel together throughout Cuba performing, Carlos on the violin and Filip on the guitar and keyboards. They recently released a CD. Their repertoire extends from Mozart to Paul Anka and includes a few popular Cuban standards. They first caught my attention in a restaurant in Viñales with their slow, soulful interpretation of the Beatles’ “Yesterday.” Like many Cubans engaged in entrepreneurial activity, Carlos and Filip make more in tips on a Saturday night than in a month of teaching.

Their friend Inés, who also returned to Pinar after graduation from music school in Havana, often travels with them, leading a group of African-style dancers. When we exchanged contact information, she glanced at the iPhone-wallpaper photo of me with my boyfriend and guessed, “¿Es tu novio contigo?”—“Is that your sweetheart with you?” I showed Ines more pictures of Jim and me together and tried to imagine people in their twenties, in the small Arizona farm town where I grew up, talking so openly about gay feelings and relationships. To be fair, I suppose, I should return to the Arizona town from which I escaped in 1967 and conduct some interviews.

While standing on a Havana street corner awaiting my companions for dinner, I saw a well-dressed young woman approaching with a warm smile. She lifted an eyebrow and asked, “Esperándome?”—“Waiting for me?” I realized that I had seen no obvious streetwalkers here, like the sluttishly clad women who flounced around the bar of the Miami Sofitel on the night before I embarked for Havana. I have read many accounts of prostitution in Cuba: it is tolerated but discouraged; disease prevention is of a higher priority than prosecution; and the government recognizes that Cuba is a destination for European sex tourists, who are a bountiful source of collateral income. But now, as I politely let the young woman know that I was awaiting my friends, I realized that prostitution is simply another manifestation of the free enterprise that is growing in the tiny cafés, nail salons, and shoe-repair shops.

A few days later, in the province of Viñales, an opportunity presented itself with an attractive young man. The strap on my old leather watchband had come unglued in the muggy heat. The hotel’s gift-shop cashier said she had no glue, and sent me to the bar. The bartender summoned Leonardo, the handyman, who studied my watch and asked my room number. He left with the watch and I downloaded photographs at the bar. When he returned, I saw that he had not glued the leather, he had sewn it, very carefully, with fine red thread. I offered him the equivalent of five U.S. dollars and he accepted half, then said with a smile, “Por qualquier cosa más—qualquier—digame” (“For whatever else—whatever—tell me”).

* As early as 2001, Amnesty International recognized that Cuba had “quite a good record on gay rights.” More recently Human Rights Watch has condemned Cuba as “the only country in Latin America that represses virtually all forms of political dissent,” including dissent by its gay citizens.

Author’s Note: The photographers’ trip in which I participated was arranged by the Cross-Cultural Journeys Foundation of Sausalito, California. Many tour companies offer Cuban travel. I can vouch for CCJ’s professionalism and the quality of their lecturers and guides.

Steve Susoyev is an attorney based in San Francisco.