David Hockney: An Exhibition

Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

Nov. 20, 2017–Feb. 25, 2018

Exhibition Catalog

Chris Stephens & Andrew Wilson, eds.

Tate. 280 pages, $100.

DAVID HOCKNEY: An Exhibitionis a global event, and it is the most comprehensive retrospective ever devoted to the eighty-year-old artist’s career. The exhibition is mounted on a grand scale, with more than 250 pieces, ranging from his early sketches made in the 1960s through video installations constructed in 2015. There are previously unseen pieces, but also the works that made him famous—double-portrait paintings, intimate homoerotic shower scenes, L.A. swimming pools, and massive landscapes from the Grand Canyon and Mulholland Drive to the Yorkshire Wolds.

The exhibition is a collaboration among three institutions: the Tate in Britain, the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, and the Met in New York. The Tate announced when the exhibition closed that it had been seen by half a million visitors. There are two exhibition catalogs, one published by the Pompidou, edited by Didier Ottinger, the other by the Tate, edited by Chris Stephens and Andrew Wilson. To coincide with the exhibition, Taschen published David Hockney Sumo, a signed collector’s edition more than two feet wide with a designer bookstand.

Hockney is best known as a painter, to be sure, but he has also worked as a book illustrator, a photographer, a printmaker, a stage designer, and a videographer. He has experimented with emerging technologies from the Polaroid to the iPad, including innovative video installations projected onto enormous screens conceived as a journey through the four seasons. Hockney’s œuvre is immense, spanning nearly five decades and encompassing hundreds of one-man exhibitions and a hundred books and exhibition catalogs—including Dog Days(1998), a book of paintings and drawings of his dachshunds, and the thoroughly researched Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters(2001). He has been the subject of various documentaries, such as The Illusion of Depth with illusionists Penn and Teller and The Colors of Music, a PBS “American Masters” episode. And, in 2014, he painted BMW Art Car, which is included in the auto manufacturer’s art collection.

Monumentality defines much of Hockney’s vision: making art on a gigantic scale; a fascination for the spectacular; epic pieces that force the viewer back from the work in order to see it. At the Pompidou, his painting The Arrival of Spring in Woldgate, East Yorkshire, 2011 (twenty eleven)(figure 1), dominated the lobby. The work, which depicts different aspects of spring, is on 32 canvasses and measures twelve by 32 feet. Hockney has gifted the painting, valued at $27 million, to the museum.

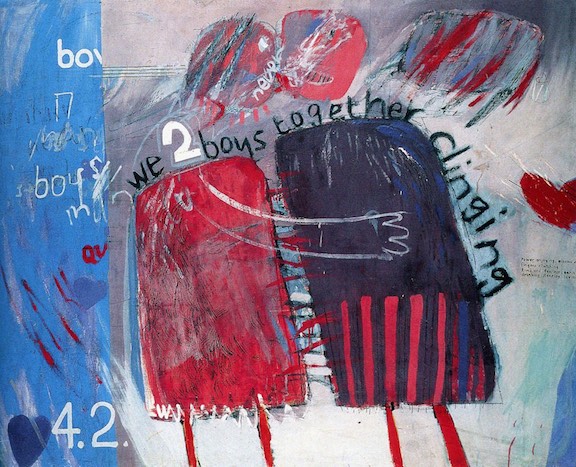

In We Two Boys Together Clinging(1961, figure 2), featuring two popsicle-like figures, he incorporates a line from Whitman’s poem of the same name: “Power enjoying—elbows stretching—fingers clutching, Arm’d and fearless—eating, drinking, sleeping, loving.” In Adhesiveness(1960), whose title is likewise drawn from Whitman—his term for intimacy between two men—there are two crudely painted figures in 69 position, fitted together like a jigsaw puzzle. In Doll Boy(1961), a representational figure emerges rather than an abstract shape, a discernible male singer with musical notes streaming whimsically from his mouth. The number 3.18 in the painting translates as Cliff Richard (coded as CR in Queen), a rock ’n’ roll singer, England’s Elvis Presley, a heartthrob who was routinely mobbed at concerts by swooning fans. Hockney was infatuated with the singer and pinned photographs of him onto the panels of his cubicle at RCA.

Hockney approaches the canvas as an arena in which to perform. In a short, seemingly uncomplicated video installation, he paints the words “Love Life” (2017) with a large, chiseled paintbrush dipped into a paint tray, and then unpretentiously signs it. This is Hockney doing artistic performance as have other artists, such as Jackson Pollack’s dance-like action painting in the Autumn Rhythm Number 30(1950), or Keith Haring’s subway graffiti painting, such as when he spray-painted Fiorucci Walls(1983) in Milan in a two-day TV performance.

Reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci, the representation of water is an obsession and a conundrum for Hockney. In his Notebooks, da Vinci listed 64 words for the way water moves, writing: “Water is the driving force of all nature.” The Bigger Splash (1967), which uses water to encapsulate the zeitgeist of L.A., is one of his best-known paintings. It delineates the result of an unseen diver’s leap from a diving board into a blue pool, disturbing the surface of the water. In David Hockney: Seven Paintings, an exhibition catalog by Catherine Kinley, the artist explained his brushstroke process: “The splash itself is painted with small brushes and little lines. … It took me about two weeks to paint. … When you photograph a splash, you’re freezing a moment and it becomes something else. I realize that a splash could never be seen this way in real life, it happens too quickly. And I was amused by this, so I painted it in a very, very slow way.”

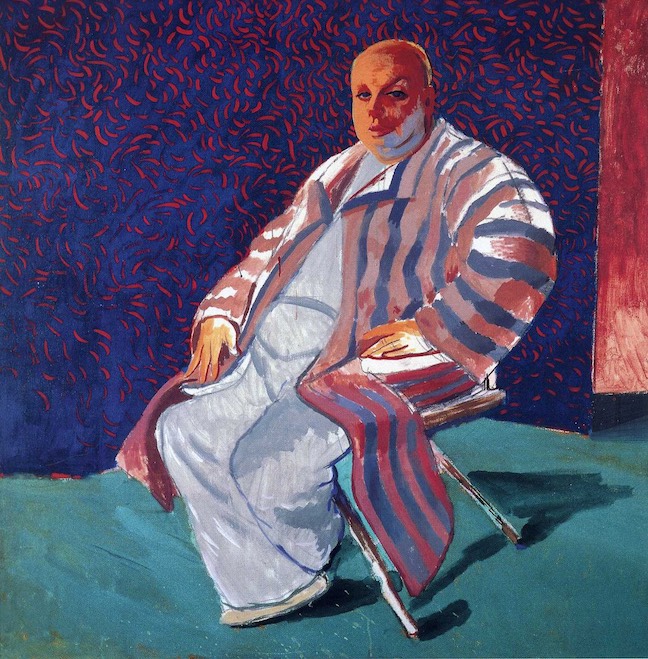

His brushstrokes became emblematic and have a performative function, recording the creative process of painting. They’ve been described by Christopher Simon Sykes as “French marks.” In Sykes’ David Hockney: The Biography(1975-2012), Hockney explains: “I thought the one thing the French were marvelous at, the great French painters, was making beautiful marks. Picasso can’t make a bad mark, Dufy makes beautiful marks, Matisse makes beautiful marks.” The French marks, Hockney’s signature brushstrokes, are evident in the background of his Divine (1979, figure 3), a portrait of the actor (Harris Milstead) made famous in John Waters’ films Pink Flamingos (1972) and Female Trouble(1974), among others.

In addition to the frequent references to Whitman, Hockney draws inspiration from other works of literature. For example, stimulated by Wallace Stevens’ The Man with the Blue Guitar, he made a portfolio of twenty etchings. Inspired by C. P. Cavafy’s work, he created Illustrations for Fourteen Poems(1966). In a collaborative project with Stephen Spender, he illustrated China Diary(1982). His close friends Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy were the subjects of one of his major dual-portrait paintings (figure 4), which was painted at their home in Santa Monica Canyon, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, where Hockney was a frequent guest.

Months before he arrived in L.A., Hockney painted Domestic Scene(1963), which shows a lanky man in a pink apron soaping the back of another man who is in the shower beneath a solid blue jet of water. Other shower-scene paintings with naked men include Two Men in a Shower(1963) and Man Taking a Shower in Beverly Hills(1964). The paintings were based on photographs from the bodybuilding magazine Physique Pictorial, which Hockney mined for images. Publisher Bob Mizer’s beefcake empire included a portfolio of more than a million images shot in fabricated domestic interiors made in his L.A. studio called the Athletic Model Guild. Some of the models included Joe Dallesandro, Jack Pierson, and Arnold Schwarzenegger before they became famous. The models wore posing straps and were never entirely nude; they were solo images and never portrayed or suggested sexual acts. The models represented an idealization of white American masculinity, com- pletely excluding ethnic diversity.

Hockney had read John Rechy’s City of Night, which described L.A. as an exotic and homosexualized utopia: “In the warm palmtreed Los Angeles night, restless they will feel the excitement.” The influence of this early gay novel cannot be overstated. Hockney told Martin Gayford in A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney(2010): “I thought [it]was a marvelous picture of a certain kind of life in America. It was one of the first novels covering that kind of sleazy, sexy hot night-life in Pershing Square. I looked at the map and saw that Wilshire Boulevard, which begins by the sea in Santa Monica, goes all the way; all you have to do is stay on that boulevard. But of course, it’s about eighteen miles, which I didn’t realize. I started cycling. I got to Pershing Square and it was deserted; about nine in the evening, just got dark, not a soul there.”

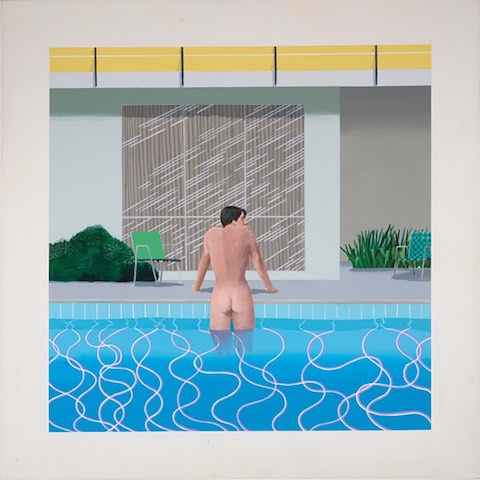

Where others found banality, Hockney found freedom and fantasy in Southern California. The ubiquity of stereotypical things—gas stations, swimming pools, parking lots, palm trees, and Sunset Strip—became objects of fascination for him to paint. (He painted swimming pools for eight years.) California was the voluptuous antithesis of scarred, austere postwar England. In Hockney: A Film by Randall Wright, the artist recalled of his World War II childhood: “We hid in a cupboard under the steps. When the bomb drops on the street, my mother screams. You scream. You’re very frightened if your mother is frightened. So, it’s something I’ve always remembered. It’s the first memory I have. … Rationing didn’t end until I was sixteen years old.” He wrote on the back of a postcard that had the slogan, “Greetings from California: Playground of the Nation”: “Arrived in the promised land 2 days ago. The world’s most beautiful city is here—L.A. You must come.” When Hockney met Peter Schlesinger, they became romantically and sexually involved, and he immediately became the artist’s homoerotic ideal and preferred model. Hockney’s bold and emotional Fauvist colors became contextualized within identity, same-sex sexuality, and those trademark bubble butts and tan lines. In Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool(1966, figure 5), Schlesinger emerges from a pool like the goddess in Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, visibly disturbing the sunlit water’s surface with squiggly white lines.

The theme of flight appears in the painting Flight in Italy-Swiss Landscape(1961) and in A Rake’s Progress(1961–63), a series of sixteen etchings that reinterpret William Hogarth’s 18th-century engravings to illustrate Hockney’s initial trip to New York. Hockney is the central figure, a young gay artist struggling to find his way in the city. The etching My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean(1961–62) is about passionate longing for another person. The Start of the Spending Spree and the Door Opening for a Blonde(1963) depicts Hockney becoming a Clairol blond because “Blondes have more fun.” He moved to L.A. in 1964 and lived there for three decades, always returning to England for brief periods, eventually moving back to Yorkshire, buying a house in Bridlington, a small coastal town on the North Sea, where he lived on and off for eight years.

Hockney says that he sees the world psychologically. His landscapes are rhythmic and do not reproduce exactly the appearance of nature. Instead, they grasp for an emotion or atmosphere. Hockney told Gayford: “Trees are the largest manifestation of the life-force we see. No two trees are the same, like us. We’re all a little bit different inside, and look a little bit different outside. … There’s a moment when spring is full. We call it ‘nature’s erection.’ Every single plant, bud and flower seems to be standing up straight. Then gravity starts to pull the vegetation down.” At eighty, Hockney has suffered several strokes, is almost completely deaf, and wears two hearing aids. He laments: “I haven’t had a really good hard-on since I had the stroke.”

The trajectory of Hockney’s life extends from brash exclamations of same-sex sexuality and audacious shower tableaus, through a tunnel, and into the woods, making suggestive landscapes referencing the power of nature. The landscapes are revelatory; they reflect memory, loss, and trauma. In a sense, he also paints from memory, because his landscapes are metaphorical celebrations of self and the universality of the human condition. Hockney lived in all of the “ground zeroes” of the AIDS epidemic—New York, London, L.A., Paris. He remarked: “The first person to die of AIDS that I knew was in 1983, and then for ten years it was lots of people.” Over his lifetime, there were many subsequent losses—intimate friends such as Isherwood, Henry Geldzahler, Jonathan Silver—each of whom had a place in his past. He painted portraits of them all. When Geldzahler, curator of contemporary art at the Met, was on his deathbed, he pleaded, “Draw me.” So Hockney did a series of poignant drawings before he died.

Today, you might find Hockney during a morning drive in his Toyota pickup-truck, a cargo bed fitted with canvas racks, stopping roadside beside an open field to paint landscapes en plein air during all seasons, no matter the weather. He has continued to make art tirelessly, always finding new subjects to be excited by, and seems determined to make good on the mantra, “Love life.”

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, documentarian, and writer for more than fifty years.