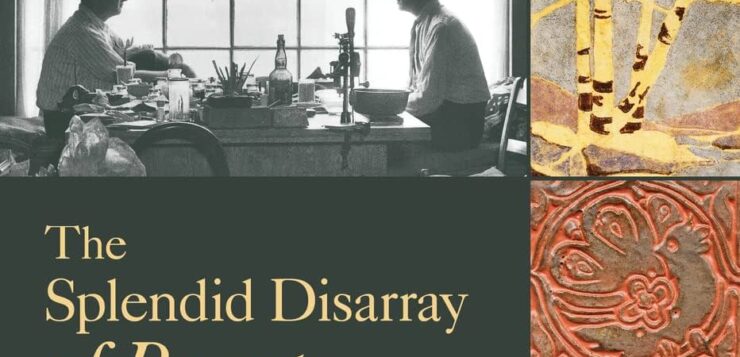

THE SPLENDID DISARRAY OF BEAUTY

THE SPLENDID DISARRAY OF BEAUTY

The Boys, the Tiles, the Joy of Cathedral Oaks—

A Study in Arts and Crafts Community

by Richard D. Mohr

RIT Press, 156 pages, $75.

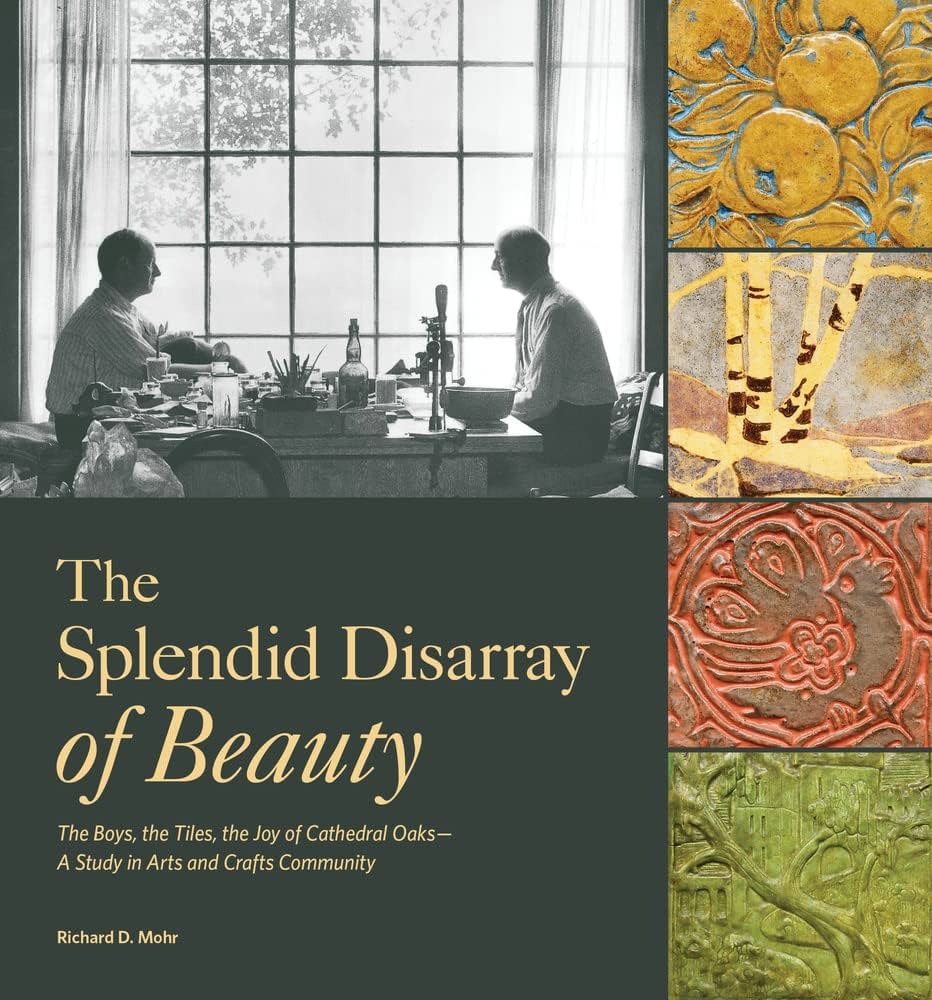

THE SQUARE CLAY tiles depict bucolic scenes in colored glazes: landscapes, billowing clouds, boats on a bay. The compositions are stunning, but the quality is terrible. Who made these items? In The Splendid Disarray of Beauty, Richard D. Mohr, a professor emeritus of philosophy and the classics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, combs through a collection of several decorative art tiles—“some of the most beguiling, beautiful, and mysterious tiles ever made in America”—for clues. Like an archaeologist reconstructing an ancient relic from a few shards of pottery, the decorative arts scholar uses the only surviving artwork from an early 20th-century, summers-only art school to piece together its past, to acknowledge its contribution to the American Arts and Crafts movement, and to explore its significance for gay history.

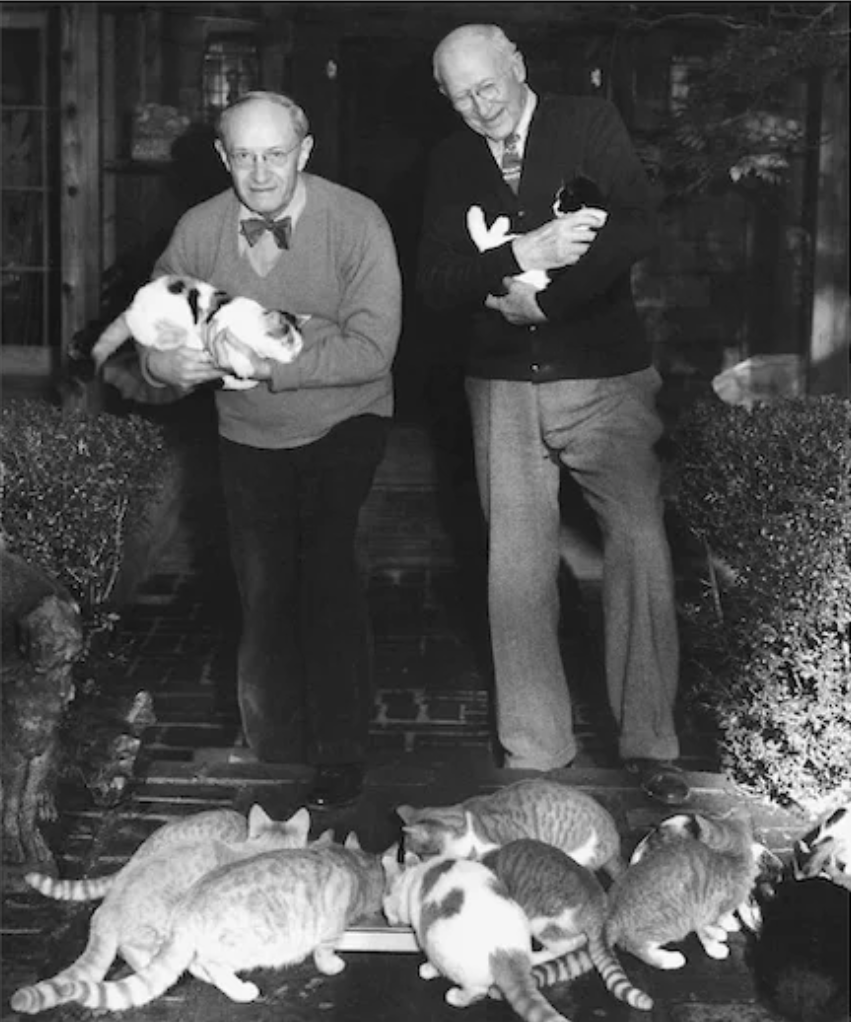

The Cathedral Oaks School of Art (1911–1914), set on 150 wooded acres in the foothills of California’s Santa Cruz Mountains, was founded by George Austin Dennison (1873–1966) and Charles Frank Ingerson (1879–1968) shortly after they met to fulfill their shared ideals: “To create beauty, to live through beauty, and to be surrounded by beauty.” Partners in business and life, the men shared a Midwestern background, a can-do attitude, and a love of hats, cats, and smoking. Their open lifestyle didn’t seem to raise too many eyebrows. Locals affectionately referred to them as “the Boys,” while a profile in their local paper called them “as ordinary as a pair of old shoes.”

The school was the men’s “honeymoon project.” Dennison drew on a marketing background and acted as the school’s manager. Ingerson, trained in the arts, served as principal instructor. Employing a small staff, they enthusiastically pitched classes in things like painting, printmaking, and jewelry-making. All of the students were women, almost all of them middle-aged, and most of them teachers and arts administrators from California, Washington, and Utah. During the six-week sessions, they could all lean into their artistic identities in an Arcadian environment.

In the school’s second year, the Boys began teaching tile-making—while the kiln was still being built. Despite the technical know-how of the school’s ceramic engineer, Albert Louis Solon (1887–1949), they were clearly figuring things out as they went along. The output of the carved and molded tile work is a marriage of beautiful design (evocative pastoral scenes, stylized perspectives) and bad technique (warping, cracking, glazes falling off).

The most impressive thing about the book is how much Mohr knows about tile-making. Detailed photo captions convey his thorough understanding of its technical complexities and his frequent exasperation over preventable errors. Glazes are “underfired and lifeless.” One tile depicting a moodily ambiguous coastline is labeled “another glorious failure” for the large crack it sustained during firing, while one portraying the pendulous flowered branches of a bleeding heart is warped, “another example of good design being defeated by technical incompetence.” Yet, despite Mohr’s grumblings about Cathedral Oaks’ production problems, his admiration for the Boys’ legacy shines through.

The school was short-lived, with no apparent heritage or artistic successors, although it did lead to the creation of three other art schools in northern California. Five years into the Boys’ relationship, their house and studio burnt to the ground. By then, they’d moved on to more glitzy careers, including a stint as interior designers, later creating the Ambassador Hotel’s famed Coconut Grove nightclub, in 1920, among other lavish installations.

The Boys’ 55-year relationship is at the heart of The Splendid Disarray of Beauty, and it’s what readers of these pages may find most fascinating. Mohr makes the bold claim that they were “America’s first gay couple” (while acknowledging that the book is a work of art history, not a biography). He includes several photographs of the pair looking cozy at home, one where they’re cuddling up to Hollywood actress Olivia de Havilland (she and her sister Joan Fontaine considered the men their uncles), and a reproduction of the Boys’ joint Christmas card from 1952. But the book’s fore-square focus—as its large square shape aptly suggests—is on the tiles.

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue and on his website, mastermichaelquinn.com.