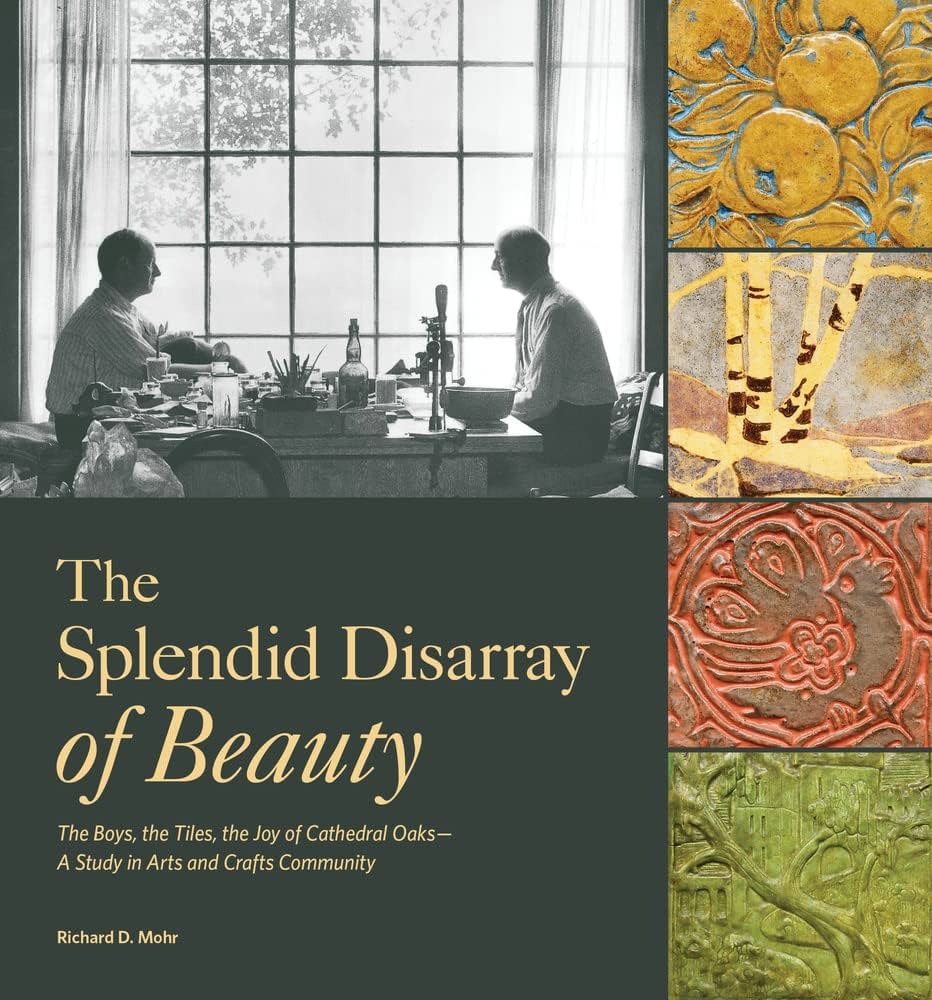

THE SPLENDID DISARRAY OF BEAUTY

THE SPLENDID DISARRAY OF BEAUTY

The Boys, the Tiles, the Joy of Cathedral Oaks—

A Study in Arts and Crafts Community

by Richard D. Mohr

RIT Press, 156 pages, $75.

THE SQUARE CLAY tiles depict bucolic scenes in colored glazes: landscapes, billowing clouds, boats on a bay. The compositions are stunning, but the quality is terrible. Who made these items? In The Splendid Disarray of Beauty, Richard D. Mohr, a professor emeritus of philosophy and the classics at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, combs through a collection of several decorative art tiles—“some of the most beguiling, beautiful, and mysterious tiles ever made in America”—for clues. Like an archaeologist reconstructing an ancient relic from a few shards of pottery, the decorative arts scholar uses the only surviving artwork from an early 20th-century, summers-only art school to piece together its past, to acknowledge its contribution to the American Arts and Crafts movement, and to explore its significance for gay history.

The Cathedral Oaks School of Art (1911–1914), set on 150 wooded acres in the foothills of California’s Santa Cruz Mountains, was founded by George Austin Dennison (1873–1966) and Charles Frank Ingerson (1879–1968) shortly after they met to fulfill their shared ideals: “To create beauty, to live through beauty, and to be surrounded by beauty.” Partners in business and life, the men shared a Midwestern background, a can-do attitude, and a love of hats, cats, and smoking. Their open lifestyle didn’t seem to raise too many eyebrows. Locals affectionately referred to them as “the Boys,” while a profile in their local paper called them “as ordinary as a pair of old shoes.”

The school was the men’s “honeymoon project.” Dennison drew on a marketing background and acted as the school’s manager. Ingerson, trained in the arts, served as principal instructor.

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue and on his website, mastermichaelquinn.com.