A GREAT PORTRAIT photograph shows the heart and skill of a great photographer, an ability to capture the moment, the personality, and temperament of the subject. I think of a portrait photograph as a mirror to both the subject and photographer.

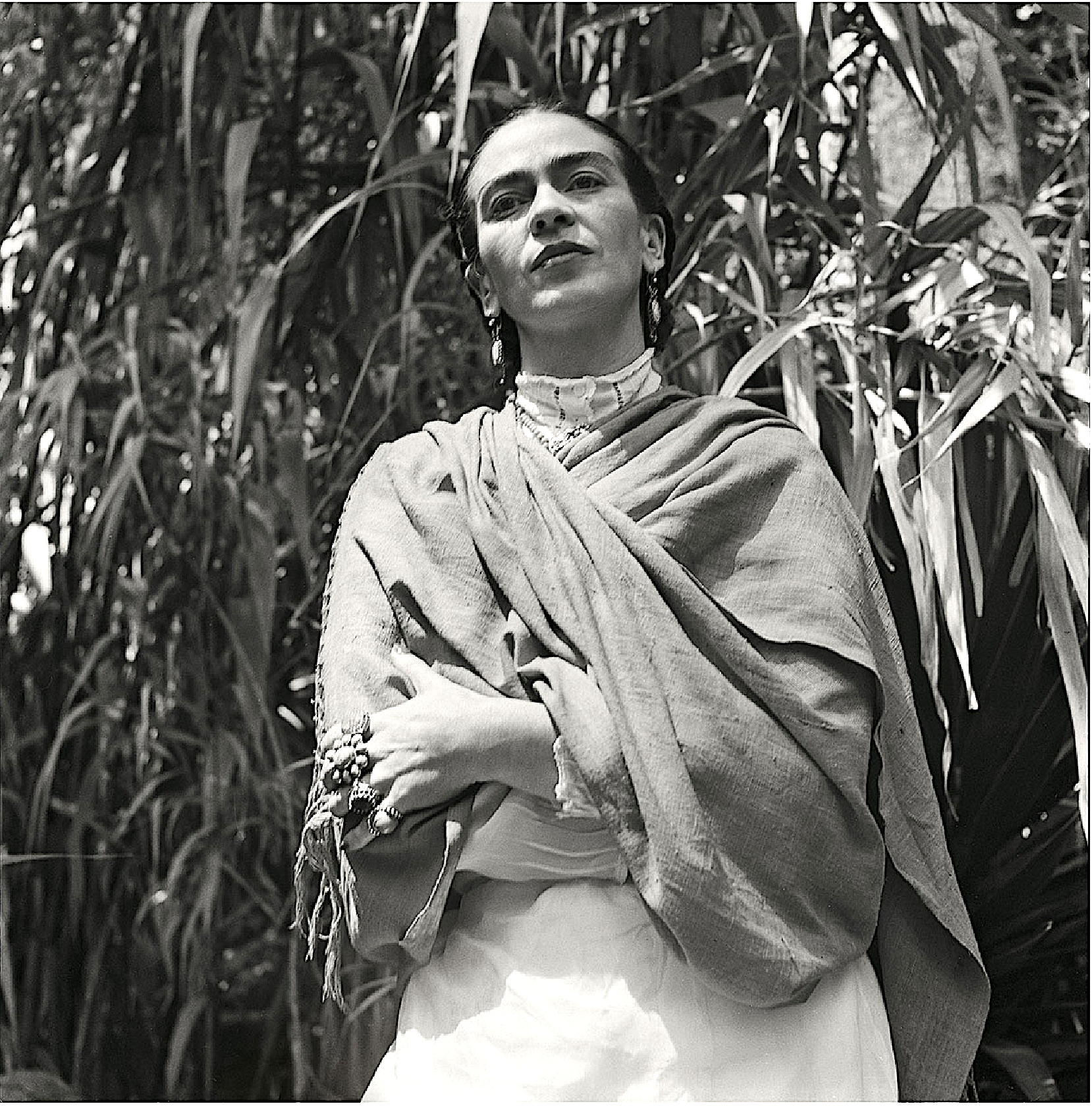

I came to know the work of Gisèle Freund in an unexpected way. As a gay woman and plant aficionado, I’ve often explored the homes and gardens of queer creative geniuses. On one memorable trip, I reserved a slot to tour the home and garden of the painter Frida Kahlo (1907–1954). From childhood, Kahlo resided in a house known as La Casa Azul in Coyoacán, a suburb of Mexico City. On one wall of her bedroom, I was struck by a black-and-white photograph of Kahlo taken late in her life, when her physical misery was intensifying. With a mantilla draped over her shoulders, her exposed hand bedecked with rings, she’s standing with a searching, reflective look, a proud figure full of grace and sensitivity despite unremitting pain. Such a memorable image! I hurriedly scribbled down the name of the photographer on my entry ticket—Gisèle Freund—but promptly forgot about it until years later, while living in London.I learned that a retrospective of Freund’s photographs was on exhibit in Paris. Resolving to check out the exhibit, I first did a little research and discovered that Freund and I had much in common as lesbians and social activists with a Jewish heritage.

Freund was born in 1908 into a cultured, wealthy family in Berlin. Her father bought her a fine camera when she was in her late teens, which started a passion that became her life’s work. Her university days in Frankfurt were spent studying the social sciences and demonstrating with other socialist students, despite the violence of Nazi thugs in the streets.

A month after Hitler came to power in 1933, she wisely fled to Paris, knowing that her politics and heritage could lead to her arrest and far worse. Having started work on an advanced degree in the arts, she continued to work on her dissertation at the Sorbonne and hone her photographic skills. A pivotal moment in her personal and professional life occurred in 1935, when Freund met the feminist writer and publisher Adrienne Monnier at her renowned bookstore, La Maison des Amis des Livres. Freund was also introduced to Sylvia Beach, the owner of the bookstore Shakespeare and Company (which still exists today).

Monnier’s Maison was a mecca for the Parisian intelligentsia—a bookstore, a lending library, a publishing house, and a space for art exhibitions. These two bookstores on the rue de l’Odéon were at the heart of the literary scene in Paris, serving as meeting spots for English and French writers (among others). Monnier published James Joyce’s revolutionary novel Ulysses, first in English and then a French translation.

Monnier opened doors for Freund, and eventually they became lovers. Freund moved into her apartment. Their relationship lasted until 1940. In that perilous time, it was wise to become a French citizen rather than remain a German refugee, and the best way to do that was by marrying a Frenchman. Monnier arranged to have Freund marry a pal of hers, one Pierre Blum (but they agreed to get a divorce as soon as the war was over). Freund swapped her German-sounding first name (Gisela) for Gisèle.

Before the outbreak of the war, Freund made hundreds of portraits of Europe’s elite artists, writers, iconoclasts, and sexual outlaws. My favorites are her portrait photos of Vita Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Simone de Beauvoir, Colette, James Joyce, Matisse, and Jean Cocteau. She was an early adopter of color photography, and, in 1938, she had her first exhibition of color portraits in Monnier’s bookshop. Throughout her career, her exhibitions and books were met with international acclaim and a steady stream of clients.

Freund didn’t see herself strictly as a portrait photographer, despite her success in that métier. She engaged in the less glamorous work of a photojournalist, bearing witness to the human suffering that was everywhere. In 1936, working for Life magazine, she photographed people living in extreme poverty during the Great Depression in England.

Her settled life ended with the outbreak of the war. Her status as a naturalized French citizen meant nothing because of her Jewish heritage. Like so many others, she fled occupied Paris in 1940, heading for southern France. There she lived underground for two years, until two prominent friends arranged for her to escape to Argentina. With the aid of a wealthy Argentinian writer and former lover, Victoria Ocampo, she settled in Argentina for the balance of the war, continuing to work as a documentary photographer and advocate for Free France. In 1954, she resettled permanently in France.

In 1950, she embarked on what was supposed to be a two-week trip to Mexico, but she didn’t leave until two years later. There she met the legendary artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Kahlo had divorced Rivera, and their complex relationship became an enduring friendship combined with political and artistic comradery. Kahlo welcomed Freund into her home, where she immersed herself in the painter’s private life, taking hundreds of photographs of her.

At the Paris exhibition, I instantly recognized Freund’s photographs of Kahlo in her bedroom, the same one I had seen years before. No other photographer was allowed this kind of intimate access to Kahlo, even showing her lying in bed. These images revealed a relaxed familiarity between the photographer and the subject. Many believe that Freund and Kahlo (who had a number of lesbian relationships) became lovers in those years. This remains a private story of Freund’s life.

Freund’s work was perhaps summed up best by the artist herself: “My camera led me to pay special heed to that which I took most to heart: a gesture, a sign, an isolated expression,” she once said. “Gradually, I came to believe that everything was summed up in the human face.”

Emily L. Quint Freeman is the author of the memoir Failure to Appear: Resistance, Identity and Loss (Blue Beacon Books).